Days that Changed the World

Hywel Williamss books include Cassells Chronology of World History: Dates, Events and Ideas that Made History, Britains Power Elites: The Rebirth of a Ruling Class, and Guilty Men: Conservative Decline and Fall. For Quercus, he has written Days that Changed the World, Sun Kings: A History of Kingship, In Our Time: The Speeches that Shaped the Modern World, Emperor of the West: Charlemagne and the Carolingian Empire, and Age of Chivalry: Culture and Power in Medieval Europe 9501450. His work has been translated into over fifteen languages and he is now writing a history of the British Isles. He has written for The Times, Sunday Times, Guardian, Observer, Times Literary Supplement, Spectator and the New Statesman, and is an Honorary Fellow of the University of Wales. His television history of the late-twentieth century was broadcast on S4C in 2009.

Praise for Hywel Williams:

EMPEROR OF THE WEST

Excellent and thought-provokingtells the story of an

iconic figure for the new Europe

Times Literary Supplement

Hywel Williamss Emperor of the West is a magisterial survey

of the great European emperor, of the Latin culture of his

court and the political extent of his domains

A.N. Wilson, Observer

CASSELLS CHRONOLOGY OF WORLD HISTORY

Staggeringly clever Guardian

BRITAINS POWER ELITES

A joy clever, polemical written with brio The Tablet

GUILTY MEN

A work of genius The Times

SUN KINGS

An accessible, wide-ranging and informative book

Times Literary Supplement

Days that Changed the World

Hywel Williams

For Virginia Fraser and in memory of Frank Johnson

New York London

2006 by Hywel Williams

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to .

e-ISBN 978-1-62365-533-4

www.quercus.com

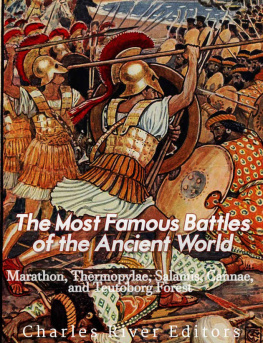

28 September 480 BC

The Battle of Salamis

The Athenian Navy Destroys the Persian Fleet

We have forced every sea and land to be the highway of our daring, and everywhere, for good or ill, we have left imperishable monuments behind us.

Pericles on the Athenians

The battle of Salamis became the first great sea-battle to be described in recorded history. It was a momentous event in the long story of the wars between the Greeks and the Persian empire. The Greek fleet was able to defeat the much larger Persian navy at the straits of Salamis located between the island of Salamis and the Athenian port of Piraeus. By 480 BC the Persian army led by King Xerxes I had conquered large parts of Greece. The Persian navy consisting of a thousand galleys was threatening to surround and overwhelm the Greek fleet of 370 triremes located in the Saronic Gulf. The eventual victory was the result of some clever Greek trickery a quality which was always a cause for Hellenic self-congratulation. The Greek commander Themistocles sent Xerxes a false message suggesting that he was preparing to change sides. Lured by the Greeks, the Persians then sailed into the narrow waters of the Salamis straits where the Greek triremes proceeded to launch a ferocious attack, ramming the Persian ships and sinking some 300 of them. The Greeks by contrast lost only about forty of their ships. The remainder of the Persian fleet had to withdraw and Xerxes was forced to postpone any further land campaigns for a year. This provided the Greeks with a crucial breathing space during which the autonomous city-states (poleis) set aside their customary quarrels. Their united armies, under the command of the Spartan general Pausanias, went on to defeat the Persians at the battle of Plataea in 479 BC.

Salamis represented the union of naval strategy with democratic zeal. In 508 BC, twenty-eight years before the battle, Cleisthenes legislation gave citizenship to all the free men of Athens including Themistocles, whose father was an aristocrat but whose mother was a non-Athenian concubine. Without Cleisthenes reform the hero of Salamis would not have been an Athenian citizen. Ten years before Salamis the Greeks had won the great land victory at Marathon when, led by Miltiades, they had defeated the Persians. This had been a victory for the spear-carriers who could afford to buy their own expensive bronze equipment. But the Persians were notoriously well equipped with cavalry and archers their countrys huge plains enabled them to train such forces, an advantage denied the Greeks with their terrain of valleys and mountains. The Persians would be perfectly capable of returning in greater numbers.

Themistocles proposed that the Greeks should exploit the difficulties experienced by Persia and her allies (who included the Phoenicians) in maintaining their naval chain of supply and lines of communication. He therefore campaigned for an expansion of the Athenian fleet, then some seventy strong. But this was a proposal with profound democratic consequences. The rich would have to pay higher taxes. Poorer voters, traditionally pro-democracy, supplied the triremes with rowers. A naval expansion therefore meant increasing the influence, and possibly the numbers, of democratic sympathizers. For the conservative and propertied classes a land campaign was always a safer bet politically since the infantry were drawn from those with more money. The 480s in Athens, despite the Marathon victory, threatened to degenerate into that endemic state of political and social conflict known as stasis to the Greeks. Silver helped to resolve the argument. The mines at Sunium, owned by the state, produced a rich extra seam in 483 and Themistocles persuaded the Athenian assembly to spend this surplus on his naval expansion programme so that Athens would have 200 triremes. He also persuaded the Greek states of the Peloponnese, including Sparta with her 150 ships, to form a combined fleet. A Spartan admiral was in command since no Corinthian or Aeginan would serve under an Athenian, but it was Themistocles who guided the strategy.

The fleet first sailed north of Euboea an audacious move since the Greek traditionally fought near their own coastal mainland. A storm inflicted heavy losses on the Persians but the subsequent battle of Artemisium was inconclusive with heavy losses on both sides. Greek disaster struck on 19 August at the pass of Thermopylae, which leads from northern Macedonia into the rest of Greece: here 20,000 Persians defeated 300 Spartans and 700 Thebans. They went on to occupy Attica and destroy Athens. Salamis was a deliverance from this humiliation.