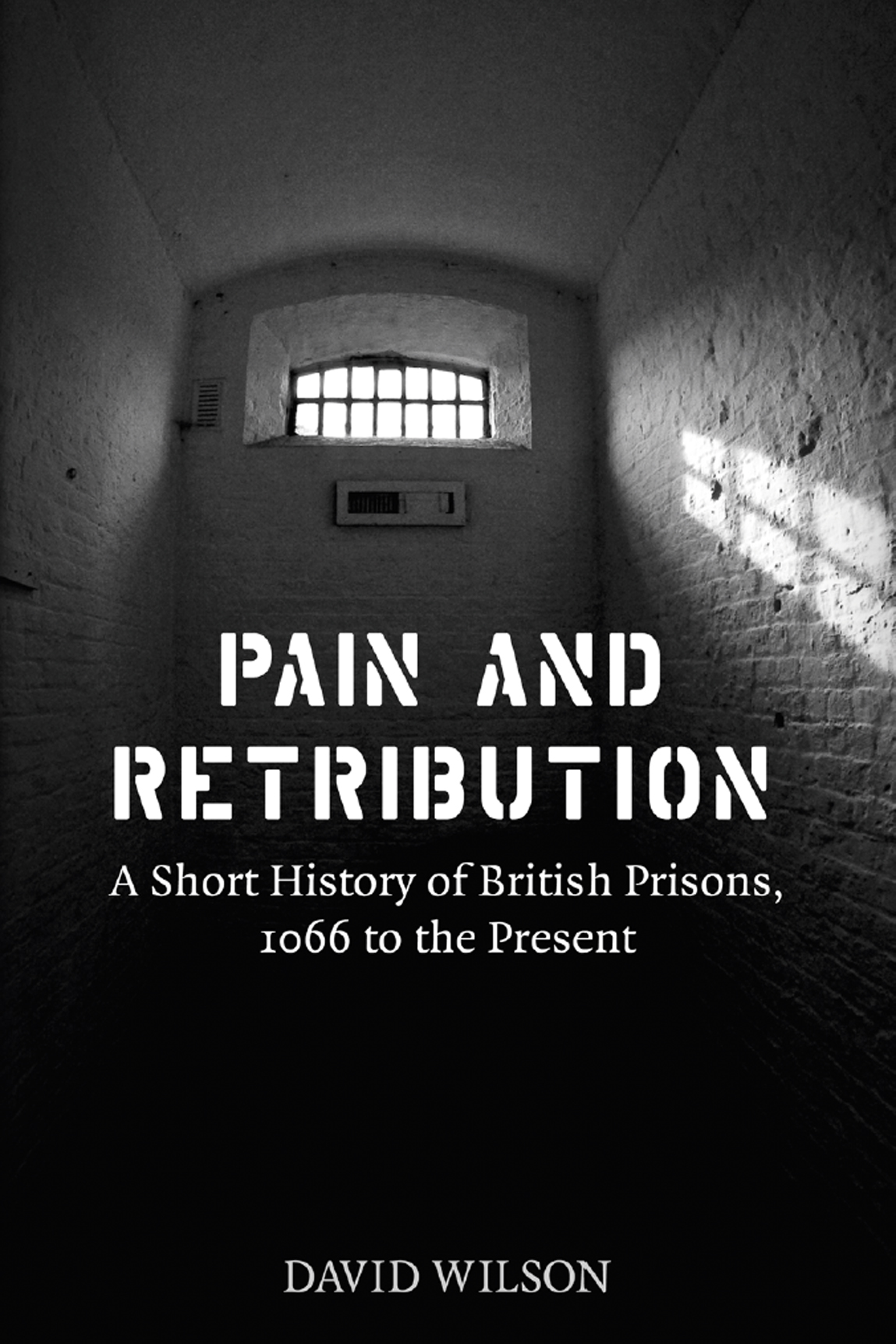

PAIN AND RETRIBUTION

PAIN AND

RETRIBUTION

A Short History of British Prisons,

1066 to the Present

D AVID W ILSON

REAKTION BOOKS

For Frances Crook my generations Elizabeth Fry

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2014

Copyright David Wilson 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780233239

Contents

Prisons, Penitentiaries and the

Origins of the Prison System

The Prisons Act of 1877 and the

Gladstone Report of 1895

Custody, Security, Order and Control,

19671991

Politicians, the Public and Privatization,

19922010

Endings and Beginnings;

Beginnings and Endings

Introduction

A number of themes guide this historical account of British prisons. First, I use the contemporary criminological idea that prison has always had to acknowledge and then satisfy the demands of three competing audiences: the public, which would include politicians, the media and commentators about prisons, as well as the general public; prison staff; and finally, prisoners themselves. The relative ascendancy and power of these three groups varies at different points in the narrative, but the need to appeal to them is used as a device to create a link both between different historical eras and between issues that emerge over the course of the period under discussion. This is a history that sees continuities, not breaks with the past.

Ultimately I will argue that it is the failure of prison as an institution to be able to satisfy all three of these audiences at the same time that leads to it being seen to be in crisis, and therefore regarded as a failure albeit a failure that continues to prosper in terms of the numbers who are sent there and the money that we spend in keeping them locked up. This will not be the last irony that will appear in the pages that follow.

And, having given my game away in the first two paragraphs, I should also acknowledge that I know that some readers might prefer their history to be written in a linear fashion, doggedly moving from one year to the next, with the relevant Acts of Parliament dutifully ticked off and stacking up, one on top of each other. However, I have allowed myself the luxury of jumping back and forth between the distinct periods being described at different points in my narrative so as to throw more light onto the issues under discussion, and to show how these issues might be understood or interpreted by my three competing audiences across the centuries. In doing so, I hope that I will be able to show that despite what we believe, or at least what we are told to believe, prisons havent really changed much at all. Nor have I felt the need to dutifully recount or even acknowledge each relevant Act of Parliament that might have been applied to prisons or those who are sent there. To have done so would have been to write a book dealing with the history of sentencing policy or of the law, rather than one specifically about prisons and prisoners.

As I hope these opening paragraphs reveal, my interest is in prison as an institution. By this I mean that I am not just concerned with who gets imprisoned, but with what happens to these people when they are incarcerated; and, more broadly, why the prison seems to have retained such a hold on our collective psyche and imagination. In doing so I will regularly use the descriptions the penal system and penal policy, which technically would include (at least) probation, but I will concentrate throughout on prisons what they look like and how they are organized and managed. I want you to walk with me on the prisons landing, meet some of the people who are being locked up there, note the remarkable absence of monsters and discuss all of this with the prisons staff. I do briefly describe the origins of the probation service and more recent attempts to punish in the community, but this is a history which charts the rise and rise of a very different form of punishment one which takes place behind the walls of an institution. At various points in time these institutions have been called gaols, jails, penitentiaries or prisons. I discuss this change of nomenclature in the text, and what the different labels mean about what happened within those walls.

At different places in the narrative I discuss policing and especially the politics of law and order. Both throw light onto who gets sent to prison and what happens to them when they are locked up, because the simple reality is that our prison system is the ultimate expression of our criminal justice process, which is usually determined by these two procedures. The politics of law and order come more to the fore as we move closer to the present day and seems to dominate contemporary discussions about prison. I wonder if this might simply be the result of the fact that fewer and fewer criminologists are actually able to conduct research within prisons; thus they are forced to analyse the institution of prison from a policy perspective instead of from their knowledge of what actually happens within the belly of the beast. Indeed, one well-known and respected criminologist who regularly writes about punishment recently told me that he had actually never been inside a prison. Where I can, I try to actually describe prisons and prisoners, as opposed to policies about prisons and prisoners.

Second, while I use a great number of official sources to guide the narrative (because these are all too readily available in print, and are collected almost fetishistically in our university libraries), given that very few people have ever visited a prison and get most of their information about imprisonment from television and films I have tried to prioritize the voices of prisoners. This has not been an easy task, and while I use prisoners autobiographies and accounts of their times inside throughout, these voices are obviously more plentiful in the contemporary period. Before the 1960s accounts were almost inevitably written by atypical prisoners such as Oscar Wilde, or by campaigners such as Charles Dickens, who made it their business to find out about what happened within the penal system. Thus I do not claim that what I have produced is a history from below if that is actually ever possible although I do believe that it is important to try to reflect how prison has been experienced by those who get locked up, even if they might be described as celebrities, rather than simply describing what is claimed for prison and how it is run, or what those with the power to make these claims and explanations argue that it achieves. Why should their claims be treated any more seriously than the claims of prisoners, or indeed of prison staff?

Prison staff of various grades, backgrounds and disciplines, and, like prisons, often described in different ways appear throughout the narra tive, although they are but one of my main interests in what follows. Even so, especially in the latter portions of the book, I try to use the voices of basic-grade prison officers (please note that the title warder was abolished in 1922) to throw some light onto the themes which have preoccupied the narrative, and to provide some insight into how these officers make sense of their responsibilities given that they have become one of the audiences that seeks to legitimize prison. After all, it is a very odd choice of career to deprive people of their liberty and to spend all of your working days locking them up.