Surviving Russian Prisons

Surviving Russian Prisons is dedicated to

Alasdair Campbell and Rosemary Piacentini

and also to the memory of my father,

Andrea Piacentini

Surviving Russian Prisons

Punishment, economy and politics

in transition

Laura Piacentini

First published by Willan Publishing 2004

This edition published by Routledge 2013

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (8th Floor)

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Laura Piacentini 2004

The rights of Laura Piacentini to be identified as the author of this book have been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Publishers or a licence permitting copying in the UK issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE.

ISBN 1-84392-103-0 Hardback

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by GCS, Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire

Project managed by Deer Park Productions, Tavistock, Devon

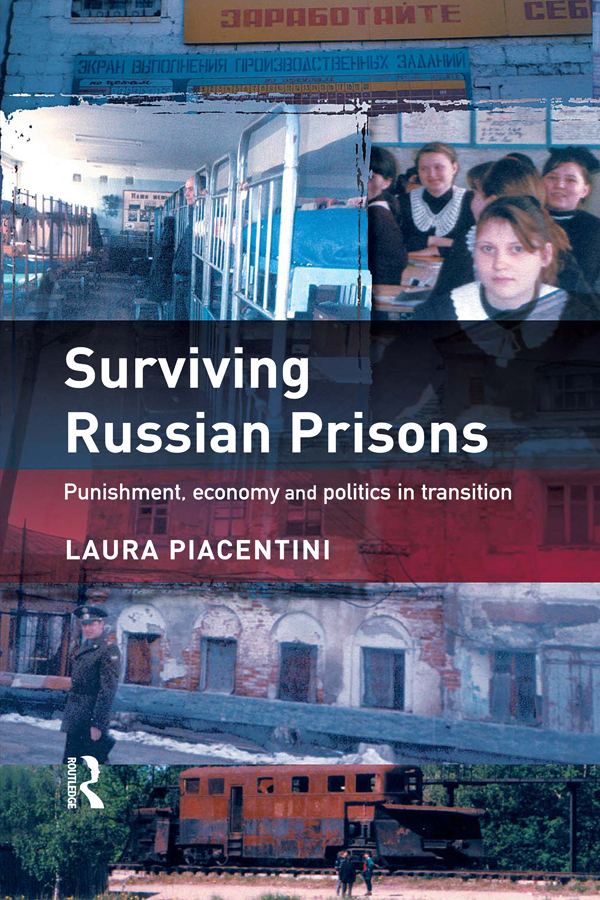

Cover photos Laura Piacentini. Top left: Zhilaya Zona (prison living zone at Omsk; top right: classroom in the educational colony for girls in Ryazan, Western Russia; bottom: prison buildings at Omsk; bottom: rusting train sitting on a track inside the prison colony at Smolensk.

Contents

List of tables and figures

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the ESRC for providing an award (number R00429825847) for funding the main study on which this book is based. Thanks also to the Department of Applied Social Science at the University of Stirling for providing financial assistance for a research trip to penal colonies in eastern Siberia in 2003.

The debts that accrue in any piece of writing can be considerable; they are the more so in a research study of this type as I depended on the expertise, patronage and kindness of a great number of people in the UK and in various locations throughout Russia. I first wish to thank Dr Yvonne Jewkes for her enthusiastic support over the various stages of writing this book and for her very useful comments. I would also like to thank my colleague, Dr Reece Walters for his sound advice and great support. Since the book is based on my PhD, I would like to say thank you to my PhD supervisors Professor Roy King and Professor Alexander Solomonovich Mikhlin in (respectively) the UK and Russia for backing the research. I am very grateful to General Alexander Illych Zubkov who, when he was Deputy Prisons Minister at the central prison authority in Moscow in 1999, did this research a great service by sending me to Siberia. I am indebted to Colonel Alekseii Vasilievich Voronkov, Junior Prisons Minister, who granted me unlimited access to Omsk and Kemerovo prison regions in 2003 and who responded cheerfully to my many requests for an interview. I am indebted to the prison chiefs of the Smolensk, Omsk and Kemerovo regions (respectively, General Anatolii Alekseivich Sahkarov, General Yurii Karlovich Baster and General Valerii Sergeivich Dolzhantsev) for generously supporting the research.

Looking back, I am amazed that all the prisoners I came into contact with, and who were incarcerated under extremely difficult physical conditions, were so open to the research. I would like to thank all of them for sharing their thoughts on imprisonment. I am grateful to the dozens of prison officers and their families for supporting my research and my needs as best they could, and for their tolerance and many kindnesses particularly as I was the first Westerner to visit the prison colonies. Thanks also to Valerii Abramkin, Director of the Moscow Centre for Prison Reform, for organising interviews with survivors of Stalin's Gulag. At the International Centre for Prison Studies in London, Professor Andrew Coyle and Anton Shelupanov provided thoughtful insight into human rights in Russian prisons. Special thanks to Nataliya Radievskaia, who helped with some of the translations.

I would also like to thank a group of people have given me fantastic encouragement at various periods. In alphabetical order: Aurora Alvarez, Hillary Bradshaw, Pat Carlen, Nils Christie, Howard Davies, Claire Davis, Rhian Evans, Brian Irvine, Laura Irvine, Andrew Jefferson, Emma Maddocks, Dominique Moran, Karrie Munro, Igor and Irina Nishchita, Judy Pallot, Jenny Parry, Konstantin Petrovich, Alan Prout, Muzammil Quraishi, Paddy Rawlinson, Deborah Ritchie, Viktor and Rita Shambulatov, Valya and Andreii Shildov, David Smith, Caroline Thomas, Tanya and Marina Varlashina and Roy Walmsley. Thanks to Brian Willan for being an enthusiastic and efficient publisher. As usual, I received enormous support from my family.

Finally, very special thanks must go to Alasdair Campbell whose unflinching support and wonderful humour kept me sane throughout this adventure.

Introduction

What do Russian prisons look like? Who is sent to prison in Russia? How is punishment allocated and administered? Few of us pause to answer these questions not least because the traditional domain of criminological research is in English-speaking countries and Western Europe. This book aims to answer some of these questions by embarking on a journey that begins by exploring how the prisons have survived the collapse of the USSR, and ends with a discussion of global penal politics. Indeed, this is the first book to be published in the West on penal practices in the contemporary Russian prison system that is an original English-language publication.

Given this hitherto exclusion, it is hardly surprising to find that there is only a handful of Russian-speaking Western criminologists conducting empirical and theoretical research on Russia's vast and complex prison system. I have worked in the area of Russian prisons since 1997 and I have been interested in Russian culture since around 1992. These interests have led me deep into that country's prison life. I have mastered Russian and lived in the natural setting of prison colonies. I have shared vodka with prison officers as they mourned the sorry state of their nation and I have been an honoured guest at musical concerts performed by prisoners. From my unique experience of prison research in 15 prison establishments, I have formed the view that imprisonment, and specifically prison labour, is ingrained in the psyche and in the social lives of Russian people. This was graphically illustrated in the spring of 1999 when broadcasts appeared on Russian television marking the two-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Russia's greatest poet, Alexander Pushkin. Vivid images of modern-day Russians in real-life settings reading aloud Pushkin's poetry were broadcast. Groups of children were shown playing and singing lullabies by Pushkin. During rare moments of rest at work, doctors appeared on television screens recounting their favourite Pushkin poem while market vendors debated the most poignant lines of Pushkin's poetry. In other words, Pushkin was everywhere. Most striking out of all the broadcasts was a series of images from Butyrka prison in Moscow and Kresty prison in St Petersburg depicting groups of prisoners reflecting on how Pushkin's poetry has enriched their lives. Russian prison authorities were unconcerned about broadcasting images from these prisons, described in 1994 by Nigel Rodley, the Special Rapporteur on Torture to the United Nations, as: An appalling reality with no daylight, fresh air and where all detainees suffer from swollen legs and feet due to the fact that they must stand for extensive periods of time and where skin disease is rife. And later by Walmsley in 1996 as: Demoralising places, uncomfortable physically and psychologically and where the stench is unbearable due to over 80% overcrowding.