O n the western edge of the ancient city of Kyoto, Japan, on the slope of Mount Arashiyama (literally Stormy Mountain), stands the Iwatayama Monkey Park. The park has winding paths and fine views of Kyoto, but the main attraction is the tribe of about a hundred and forty macaques who live there. The monkeys of Iwatayama are famously gregarious, playful, and, occasionally, crafty. Like all members of the Macaca genus, they combine sociability and intelligence. They play with their kin, watch one anothers young, learn new skills from one another, and even have distinctive group habits.

Some develop a mania for bathing, snowball-making, washing food, fishing, or using seawater as a seasoning. Iwatayama macaques are known for flossing and for playing with stones. This has led some scientists to argue that macaques have a culture, something weve traditionally thought of as distinctly human. Theyre also humanlike in their natural curiosity and cunning: one second, youre watching one do something cute, and the next second, his friends are making off with the bag of food you bought at the parks entrance.

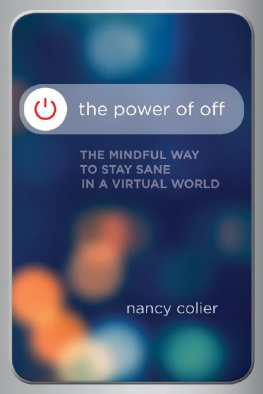

Theyre like humans in one other way. For all their smarts, nothing keeps their attention for very long. The mountainside gives them a fantastic view of one of the worlds most historic cities, but it doesnt impress them. They keep up a constant chatter, a running monologue of inconsequence. The macaques are living examples of the Buddhist concept of the monkey mind, one of my favorite metaphors for the everyday, undisciplined, jittery mind. As Tibetan Buddhist teacher Chgyam Trungpa explains, the monkey mind is crazy: It leaps about and never stays in one place. It is completely restless.

The monkey minds constant activity reflects a deep restlessness: monkeys cant sit still because their minds never stop. Likewise, most of the time, the human mind delivers up a constant stream of consciousness. Even in quiet moments, minds are prone to wandering. Add a constant buzz of electronics, the flash of a new message landing in your in-box, the ping of voicemail, and your mind is as manic as a monkey after a triple espresso. The monkey mind is attracted to todays infinite and ever-changing buffet of information choices and devices. It thrives on overload, is drawn to shiny and blinky things, and doesnt distinguish between good and bad technologies or choices.

The concept of the monkey mind appears throughout Buddhist teachingsone small indicator of the fact that the mind and its relationship to the world have been studied deeply for thousands of years. Every religion has contemplative practices, calls to use silence and solitude to quiet the mind. In John Drurys introductory note to the Anglican Matins and Evensong, he exhorts worshippers to be patient and relaxed enough to allow a long tradition to have its say and allow our own thoughts and feelings to become closer to us than life outside admits. Only then can one fully enter the cool and ancient order of the services which gives a space and a frame, as well as cues, for reflections on our regrets and hopes and gratitudes. Catholic monastics treat meditation as preparing the mind to receive Gods wisdom; the busy mind cannot hear the divine. In Buddhism, though, mental discipline is more an end in itself, rather than just a means to an end. The everyday mind is like churning water; learn to make it still, like the mirror-flat surface of a calm lake, Buddhists say, and its reflection will show you everything.

A few miles away from Iwatayama, a robotics laboratory at Kyoto University houses a robot controlled by another monkey, a rhesus named Idoya. Incredibly, Idoya isnt in Japan; she lives in North Carolina, in a neuroscience laboratory at Duke University, and her brain is connected to the robot via the Internet. The laboratory is run by neuroscientist Miguel Nicolelis, who, to make things just a bit more global, was born and educated in Brazil. Nicolelis has been studying the brain and how the brain changes as it learns executive functions; hes also developed a specialty in what scientists call brain-computer interface (BCI) technologies. Today you can buy primitive brain-wave readers that can control video games, and scientists are mapping brain functions and testing the brains ability to control complex objects through BCIs. Eventually, they hope, BCIs will be used to route brain signals around damaged nerves, restoring body control to people with spinal-cord injuries or neurodegenerative disorders.

Idoya is the latest in a series of monkeys Nicolelis has worked with. Over the previous decade, he and his team demonstrated that a monkey with electrodes implanted in its brain could operate joysticks or robotic arms with its mind. Brain scans showed something remarkable: the neurons in the monkeys frontoparietal lobethe section that controlled the animals armsfired when the monkey operated a robot arm. In other words, the monkeys brain stopped treating the robot arm as a tool, as something that it used but that was clearly separate from itself. The brain remapped its picture of the monkeys body to incorporate the robot arm. At the neural level, the distinction between the monkeys arms and the robot arm blurred. As far as the monkeys brain was concerned, monkey arms and robot arm were all part of the same body. Nicolelis and his colleagues in Japan implanted electrodes in the section of Idoyas brain that regulated walking; they then taught her to walk on a treadmill and studied how her brains neurons fired as she walked. When she obeyed commands to speed up or slow down, she was rewarded with food. They then put a video monitor in front of the treadmill. Instead of showing