RANDOM HOUSE INDIA

Published by Random House India in 2013

Copyright Karma Phuntsho 2013

Random House Publishers India Private Limited

Windsor IT Park, 7th Floor, Tower-B

A-1, Sector-125, Noida-201301, UP

Random House Group Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London SW1V 2SA

United Kingdom

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 9788184004113

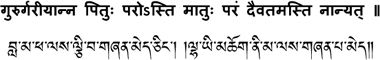

There is no guru dearer than ones father and no divinity higher than ones mother.

~ The Buddha in K emendras Bodhisattvdnakalpalat (chap. 92, v. 4)

emendras Bodhisattvdnakalpalat (chap. 92, v. 4)

To my parents

Contents

Preface

WHEN ZHABDRUNG NGAWANG NAMGYAL , the founder of Bhutan, passed away in 1651, his death was concealed through the hoax of a retreat. Meals were served on time, musical instruments were played regularly, orders issued on wooden boards and someone pretending to be him even received gifts and gave blessings from behind a curtain. The Bhutanese public were given the impression that he was in meditation but his Tibetan enemies were not easily convinced. The 5th Dalai Lama suspected that Zhabdrung suffered an inauspicious death after being struck by a fatal illness, which was caused by the Dalai Lamas own occult powers. In contrast, the Mughal governor of Bengal was told that Bhutans ruler was an ascetic, some 120 years old, living on a vegetarian diet of bananas and milk. Understandably, the mystery of his retreat gave rise to interesting and also conflicting speculations. It certainly also helped an emerging Bhutan sustain its newfound sovereignty as a unified state.

Such an enigmatic scenario is not merely a phenomenon of the distant past. Perceptions of Bhutan even in recent years were imbued with a similar sense of mystery and contrasting views. While many saw Bhutan as a happy country of exceptional natural beauty and cultural exuberance, some held views of Bhutan in less favourable terms as an autocratic third-world state. These perceptions often veered to extremes, with one group romanticizing Bhutan as a modern Shangrila while the other portrayed Bhutan as a genocidal state. Like the mystery concerning the founders death in the seventeenth century, the intrigue entailed by these biased perceptions in some ways also helped Bhutan underline its security and sovereignty. Similarly, just as the medieval government promoted the retreat hoax, the modern Bhutanese government endeavoured to convince both its citizens and the outside world of Bhutans special position as a happy land with a rich blend of culture and nature.

However, until recently, most people outside the Indian subcontinent have not even heard of Bhutan. Due to its small size, insignificant economy and the lack of reliable information about it, Bhutan largely remained an obscure country. Consequently, Bhutanese travelling abroad would have to often endure delays at immigration check points and embassies, as immigration officers struggled to locate the country. This changed in the last couple of decades as the travel culture rapidly increased in other parts of the world, and Bhutan, with its high-value tourism policy, has now become an exotic and much-desired travel destination. As a result, the number of tourists who visited Bhutan shot up from 6,392 in 2001 to 1,05,414 in 2012 and included a large number of Indian visitors who travelled by land.

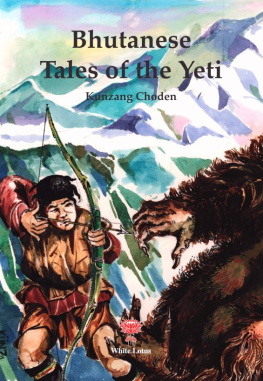

Yet, detailed and objective information on Bhutan is still sparse. Apart from a handful of books by foreign scholars and local Bhutanese writers, most publications are colourful pictorial books or sentimental travelogues by visitors to the country. Most of these sources present a nostalgic account of Bhutan with a heavy dose of Orientalist romanticism and often betray the authors own subjective susceptibility more than they report the actual situation in Bhutan. In addition to this, the government has actively engaged in a calculated effort of packaging and branding the country as a whole in order to appeal to the external expectation and sensibility. The recent efforts of the government to promote Gross National Happiness as a new economic and development paradigm in forums such as the UN has further complicated peoples imagination of Bhutan both at home and abroad. Increasingly, more and more people now describe Bhutan as a happy country, despite the fact that a large percentage of the Bhutanese live in depressing poverty and many Bhutanese youth would willingly grasp the opportunity to work in an American kitchen or European warehouse if given the chance. Moreover, none of the existing sources on Bhutan also adequately discuss the seriousness of the sociocultural transformations, which is fundamentally changing the worldview, cultural ethos and social fabric of Bhutanese society today.

In contrast to popular writings, most of which shangrilize Bhutan, the academic accounts of Bhutan generally provide readers a fairly sober account. Although they are fewer, these writings give readers information about Bhutan in some depth and detail. Yet, many academics approach Bhutan with a prior knowledge of Tibet and often show a nave tendency to Tibetanize Bhutan. A very good example for demonstrating this is the application of the la suffix, which is added after first names in conversations to address people in the honorific form in Tibet. Although the la suffix may be added at the end of a phrase or sentence (see considered pejorative to address poeple with a la suffix attached to their names. Many acclaimed scholars on Bhutan, unaware of such cultural and linguistic nuances, confidently use the la suffix after a name in imitation of the Tibetan practice.

Such nonchalant Tibetanization of Bhutan can be also found in numerous other caseseven in writings of scholars on the Himalayas and Bhutan. A well-known example is the following introduction to Bhutan by two doyens of Tibetan Studies, Hugh Richardson and David Snellgrove; it is cited by two pioneering historians on Bhutan, Michael Aris and Yoshiro Imaeda, in their introduction of Bhutan.

Thus, of the whole enormous area which was once the spirited domain of Tibetan culture and religion, stretching from Ladakh in the west to the borders of Szechuan and Yunnan in the east, from the Himalayas in the south to the Mongolian steppes and the vast wastes of northern Tibet, now only Bhutan seems to survive as the one resolute and self-contained representative of a fast disappearing civilisation.

While it cannot be denied that Bhutan is closely linked to Tibet in its religious culture and is now often called the last bastion of the Tibetan Buddhist civilization, the general cultural affinity between Bhutan and Tibet outside of the religious influence is far more tenuous than most experts on Tibet would have us believe. Thus, against the general tendency of Tibetologists to treat Bhutan as an extension of Tibet, we must distinguish one from the other, at least to the extent Japan is distinct from China or Nepal is from India. It will become clear from the following discussion of history that for nearly half a millennium Bhutan and Tibet had separate political and sociocultural existences, which have led to stark differences even in the religious cultures. Such differences have only become further entrenched and distinct after Bhutans northward link to Tibet was severed in 1959, following the occupation of Tibet by China.

Next page

emendras Bodhisattvdnakalpalat (chap. 92, v. 4)

emendras Bodhisattvdnakalpalat (chap. 92, v. 4)