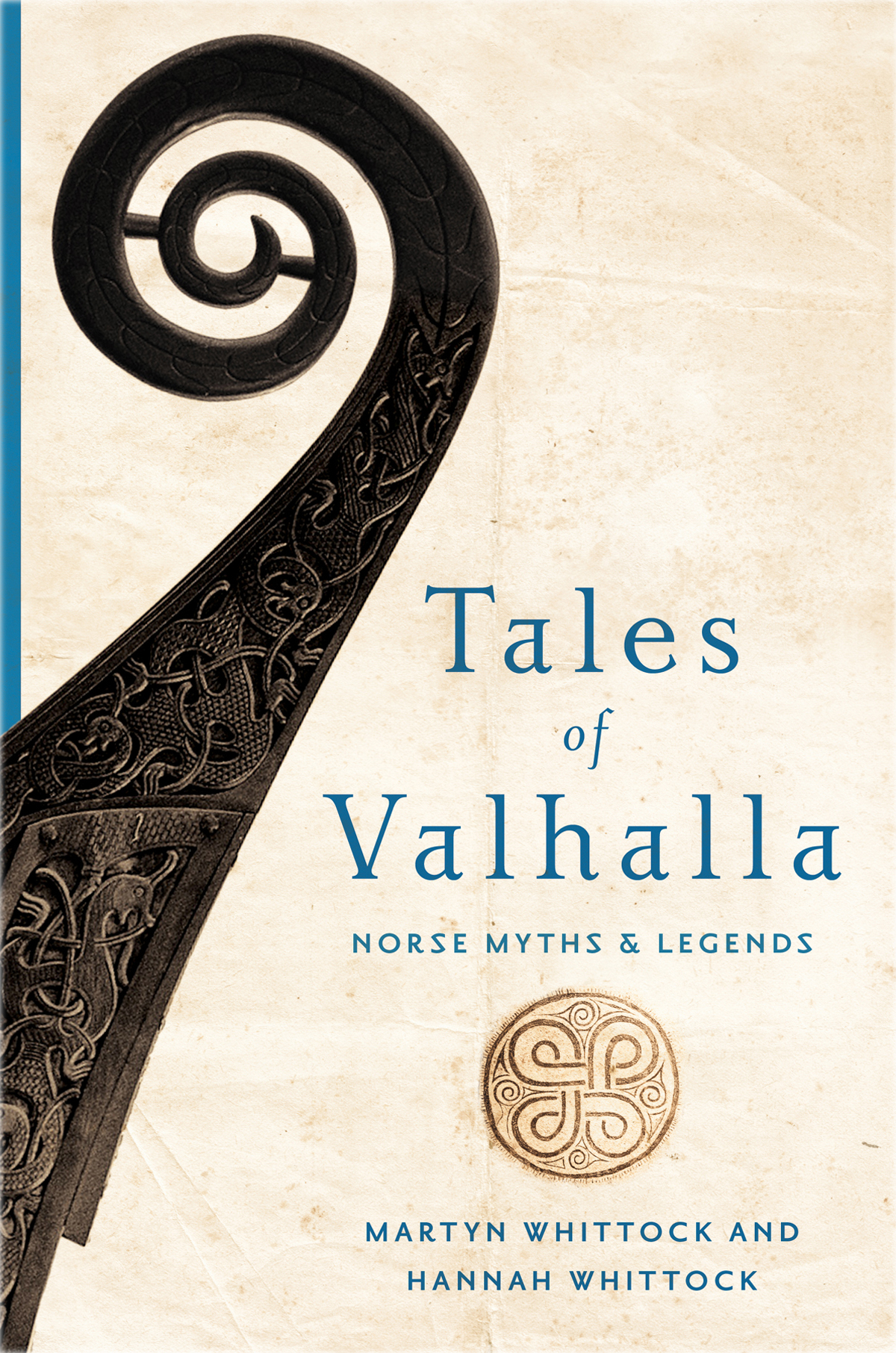

Tales

of

Valhalla

NORSE MYTHS & LEGENDS

MARTYN WHITTOCK AND HANNAH WHITTOCK

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

To Neal, Elizabeth, Lesley and Debbie.

Remembering our fun times in Brussels. HEW

Contents

T HE NORSE MYTHS have gained widespread attention in the English-speaking world. This is largely due to a great interest in the myths and legends that lie behind the world of the Vikings (the Norse) and also through a Scandinavian diaspora (especially in the United States), which has communicated these myths to the wider world.

That there is such a widespread interest is demonstrated by the appearance of Norse mythological themes in popular culture. Films such as Thor (2011), Thor: The Dark World (2013) and the Avengers films featuring Thor (the latest being Avengers: Age of Ultron, 2015) demonstrate the enduring interest in reworkings of and spin-offs from Norse mythology. These particular films are adapted from the Marvel Comics superhero, whose creators (Stan Lee and Jack Kirby) based their character of Thor on the Norse mythology of the thunder god. Furthermore, the Middle Earth of Tolkien (as seen in both The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit) is heavily indebted to Norse/Germanic mythology.

This is nothing new, since these stories have been quarried and adapted across time and culture. From medieval Icelanders celebrating their Viking roots as they recorded these myths, to William Morriss poem, Sigurd the Volsung. From Wagners Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung), to J. K. Rowlings werewolf, Fenrir Greyback. From the twentieth-century manipulation of Norse mythology by the Nazis and their allies, to modern commercial and cultural references to Norse myths in order to promote sports teams, beer, restaurants and much else. Clearly, Norse mythology continues to influence a range of aspects of modern culture.

The question is: what are the ancient stories that lie behind these later recreations and reinterpretations? This books aims to both provide a retelling of these dramatic stories and also set them in context so that their place within the Viking worldview can be understood. These are not new translations of the myths and legends. This is because there already exists a number of academic translations from the Old Norse language; and also because the accounts even when expertly translated can still be difficult to follow. Instead, these are freely worded retellings that are based on the original accounts but which present them in an accessible way as stories that can simply be read as such. They have been chipped out of the matrix of (mostly Icelandic) medieval accounts, in much the same way that a fossil-hunter disentangles one dinosaur fossil from the bones held within a mass of rock. As a result, the single stories and accounts can then be explored by a modern reader.

The stories in question are Norse myths (stories, usually religious, that explain origins, why things are as they are, the nature of the spiritual) and, to a lesser extent, legends (stories that attempt to explain historical events and that may involve historical characters, but are told in a non-historical way and often include supernatural aspects). Between them they take us into the mental world of the early medieval Viking Age.

With regard to language, Old Norse used letters that are no longer used in Modern English. In almost all cases we have translated these letters into modern English ones. So, to give an obvious example, we have anglicised inn to the more familiar form of Odin. However, very occasionally, they will appear when referring to a source, personal name or place name that employs these, along with modern Scandinavian letters not used in English when they appear in modern place names, etc. The one exception is sir (one of the two families of Norse gods), where we have used this form due to its frequent use in many modern sources, rather than the anglicised form of Aesir.

With regard to written sources, we have referred to them in an anglicised form, so Grimnirs Sayings rather than Grmnisml. Where a word, phrase or source is given in Old Norse it is always accompanied by a translation such as: Heimskringla (Circle of the World) or the personal name Bodvar Bjarki (bjarki means little bear). Occasionally a medieval manuscripts name is given without translation (such as the Codex Regius) because this is the usual convention.

In 2013 and 2014, co-author Martyn Whittock visited Iceland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden as part of the research for this book (including exploring the manuscript evidence in the Culture House exhibition in Reykjavik). Hannah Whittock (with a First and an MPhil. from Cambridge in Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic studies) has brought a detailed knowledge of the Old Norse texts and their themes to the project, along with skills in reading Old Norse (the language of the original accounts).

We are much indebted to the scholars, whose expert translations have assisted us in our own freely worded retellings of these myths and legends, and a selection of these are listed in a Select Bibliography at the end of this book. Readers who wish to study these myths in the context of the literature within which they were first recorded can access them in these translations.

Any errors, of course, are our own.

Martyn and Hannah Whittock

B EFORE WE EXPLORE a selection of Norse myths and legends, it is helpful to understand something about what is covered by the term Norse. Where and when did they live and what was the geographical spread of their influence?

The term Norse is used to describe the various peoples of Scandinavia who spoke the Old Norse language between the eighth and thirteenth centuries AD. While it had eastern and western dialects it would have been generally mutually understood across the range of areas within which it was spoken. A third recognisable form was spoken on the island of Gotland.

The Old Norse language later developed into modern Danish, Faroese, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish. In addition, there once existed the so-called Norn languages of Orkney and Shetland that are now extinct. It was, essentially, the language of the Vikings. Consequently, this book is basically about the myths and legends of the Vikings.

The Vikings and the extent of their settlement

The term Viking is itself a controversial one. At the time, it described more of what one did (raiding, pirating, adventuring) than what one was. It did not originally have an ethnic meaning but it has come to have that in modern usage. Consequently, today we use the term Viking to describe Scandinavians of the so-called Viking Age. It is in that sense that we will use it in this book.

The Viking Age lasted from the late eighth century until about 1100. It was in this period of time that people from Scandinavia first raided and then settled in a wide arc of territory that stretched from Russia in the east to Greenland and the coast of North America in the west. They raided both sides of the English Channel and settled in Normandy, eastern and northern England and the northern and western isles of Scotland, and established a Viking kingdom in Dublin. It was these peoples who colonised Iceland, the Faroes and parts of Greenland. More distant raids even reached Spain and into the Mediterranean.