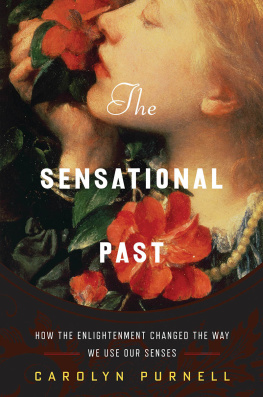

THE

SENSATIONAL

PAST

PAST

How the Enlightenment Changed

the Way We Use Our Senses

CAROLYN PURNELL

W. W. Norton & Company

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923

New York | London

To Betty, Johnny, Linda, and Albert.

The most fundamental things I know about feeling,

I learned from you.

Copyright 2017 by Carolyn Purnell

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Brooke Koven

Jacket design by Martha Kennedy

Jacket art: Portrait of Dame Ellen Terry by Watts, George Frederick; National Portrait Gallery, London, UK; Bridgeman Images

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Purnell, Carolyn, author.

Title: The sensational past : how the Enlightenment changed

the way we use our senses / Carolyn Purnell.

Description: First Edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2017. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031574 | ISBN 9780393249378 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Senses and sensationHistory18th century. |

EnlightenmentInfluence.

Classification: LCC BF233 .P87 2017 | DDC 152.109/033dc23 LC record

available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031574

ISBN 978-0-393-24936-1 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

We are amazed by thought, but sensation is just as remarkable.

VOLTAIRE,

Philosophical Dictionary

The basic narrative centers on something called the Great Divide Theory, which originated with Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s and was elaborated upon by Walter Ong in the 1980s. These theorists saw modernity as the culmination of a long historical process that led people to rely overwhelmingly on their eyesight. The long-ago shift from oral culture to print culture meant that history became transmitted through texts rather than oral traditions. By the fifteenth century, thanks to the invention of the printing press, even more people gained access to the printed word. As print culture spread, people placed their trust in the authoritativeness of texts.

According to this theory, the eighteenth century was the dividing point from previous centuries of slow development. During this period, literacy boomed, a newfangled medium called the newspaper was created, and letters circulated freely. Even the name of the Enlightenment belied the periods trust in eyesight, with illumination serving as the cultures key metaphor for reason, understanding, and social progress. Moving forward, modern intellectual life, media, and culture was ocularcentric, and throughout the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, this reliance on vision has continued, if not grown. Not all historians agree with McLuhan and Ongs ideas about oral and literate cultures, but the basic idea that we rely on our eyes more than our other sensory organs is still prevalent.

This narrative has been adopted and adapted by a number of scholars of modernity. Martin Jay has written on the scopic regimes of modernity, acknowledging, It is difficult to deny that the visual has been dominant in modern Western culture in a variety of ways.

On a basic level, these claims make a lot of sense. Literate societies do rely heavily on their eyesight, and with the proliferation , I showed how scientific observation in the early nineteenth century relied, not only on the eyes, but also on odor and taste. And these examples only scratch the surface. The picture that I have tried to paint of the long eighteenth century is one that focuses not on sights rise to prominence, but on a concept of the senses that would have been more popular in the eighteenth century itself: the idea that the senses are deeply interconnected. Perception is not just the sum total of separate, easily separable parts. Its constantly evolving, complex, and multifaceted, and we need to come up with a more holistic understanding of perception in order to come to grips with how our minds and bodies work.

While a number of Enlightenment writers praised eyesight, the sources simply dont bear out the claim that other senses were sidelined in this period. For a sense to be sidelined, it has to lose some cultural value; people have to think of it less and care about the other senses more. I would argue that the fact that we exercise more control on our sensory environments doesnt mean that we value our senses less. Take odor. Walking down the aisles of any grocery store, its possible to find deodorants, deodorizers, and odor neutralizers, giving credence to the fact that we strive to exercise more, rather than less, control over odors. I determine what I want my clothes to smell like, what I want my carpet to smell like, even what I want my garbage bags to smell like. But this is a far cry from the argument that smell is repressed in the modern West. In many cases, deodorized air is simply a blank slate for the odors that we do want to smell. Scented candles, wax burners, aromatic lotions, fragrant soaps, and other odor-oriented products are available in abundance. The vigilance with which we attend to odors shows that they still matter to us. In fact, Id argue that smell might even have a heightened effect in a world in which scent is so strongly controlled, because if something violates our neutral sphere, we notice it even more. If I came home to a nauseating odor of rotting meat, that scent certainly wouldnt strike me as marginal. Indeed, scent might even take on new importance in the modern world, offering new opportunities for self-definition. In the premodern world, everyone would have smelled of musk, onion, or other strong odors, all oriented toward fighting off miasmatic air. In the modern world, where concepts of cleanliness and air have shifted, its possible to decide whether the scent of carnation or sandalwood is more me. Our frame of reference for odor has shifted significantly, but a change in meaning doesnt necessarily mean absence.

Im not out to sweep away all the scholarship thats come before, deny that eyesight is important in modern life, or refute the claim that our sensory expectations have changed radically. The concept of sensory hiearchies, where certain senses dominate Hierarchies pit different aspects of ourselves against one another that, more often than not, work in tandem. For instance, eating a salty potato chip will certainly engage the sense of taste. But it also will engage the sense of hearing (the crunch when you bite down), the sense of touch (the crispy shards and greasy feel), the sense of smell (the glorious aroma that seems to emanate from all things fried), and the sense of sight (you may pick out the chips with black spots or decide which chip to eat first based on its pleasing shape). We have a unified perception of the experience, but its reliant on the cooperation of many senses.

Next page

PAST

PAST