For Miko. Thank you to Bridget Watson Payne, Natalie Butterfield, Allison Weiner, and the rest of the Chronicle team; Leonardo Santamaria for endless assistance; Paul Rogers, Nicholas Blechman, and Paul Sahre for inspiration and friendship; Pablo Delcan for collaboration; mom and dad for inspiring this book; Lucienne Brown for laughter and editorial support; Ron Minard for showing me how to live; the Nilsson family for sharing their island; Mike Rea and Paul Rea for brotherhood; Eric Hoover and Betty Mae Flaherty for believing in me; Uncle Chick for a childhood full of great stories; and Kristina Nilsson for love. Copyright 2019 by Brian Rea. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-4521-7923-0 (epub, mobi) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

For Miko. Thank you to Bridget Watson Payne, Natalie Butterfield, Allison Weiner, and the rest of the Chronicle team; Leonardo Santamaria for endless assistance; Paul Rogers, Nicholas Blechman, and Paul Sahre for inspiration and friendship; Pablo Delcan for collaboration; mom and dad for inspiring this book; Lucienne Brown for laughter and editorial support; Ron Minard for showing me how to live; the Nilsson family for sharing their island; Mike Rea and Paul Rea for brotherhood; Eric Hoover and Betty Mae Flaherty for believing in me; Uncle Chick for a childhood full of great stories; and Kristina Nilsson for love. Copyright 2019 by Brian Rea. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-4521-7923-0 (epub, mobi) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN: 978-1-4521-7255-2 (hardcover) Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190. Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Finding a balance between living and workingI have heard this phrase often. What does it actually mean? Does it mean working less? Does it mean vacationing more? And why is it we work so hard if, in the end, we regretfully look back at all the years we squandered away thinking we should have been enjoying them? I have thought about this a lot, and Im guilty of doing this as well. I paint and draw pictures for a living. Its a passion careerI followed a talent I had because it was what I loved to do more than any other career option.

There are many benefits to being an artist that Im grateful for, but if there is any downside, it might be that Im never able to shut things down. There are very few breaks from working or thinking about working; theres always a project in my mind, something Im working on at the moment, or a new potential project down the road. My older brother, conversely, doesnt love his job, but he loves spending time with his wife and two kids. I admire him. He has a time-share in Orlando. Prior to working as an artist, I worked as an art director at the New York Times.

I oversaw a daily section of the paper. Tasks involved commissioning artists, designing layouts, overseeing digital projects, and managing everything through to the finish, around 6 p.m. each day. I was always nervous; I sat in a cubicle that had my name next to it; I had bosses above me whom I answered to; and I wore suits to work. I worked there for nearly five years. I learned so much and I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity.

But if Im being honest, that was a crazy job. I still have anxiety dreams about my time there. During my final year at the New York Times, I began compiling a list in my sketchbook of things that were making me anxiousthings like deadlines, falling scaffolding, alien abductions, etc. After doing this for a few months, I realized there was some stuff I needed to work out. So I began to consider a move. On Thursday, June 5, 2008, Alain Robert, a French climber known for scaling many high-rises around the world, free-soloed the New York Times building.

No ropes, 52 stories up. I remember being pressed up against the glass watching Mr. Roberts progressall of us workers jockeying to get a better look, as if a unicorn had flown into our offices. It was extraordinary. In one of the busiest, most cramped, and most suffocating places in the world, Mr. Robert did something so completely free, untethered in life and in his work.

When I raced into my editors office and asked Have you heard theres a man scaling the outside of the building?! His only response was, Yes. Hes French. It was magic. Shortly after my father retired in 2001, I flew back to visit him and the rest of my family in Massachusetts. On the occasions I visit, my father is always there to pick me up at the airport. The drive from Logan airport in Boston to my parents home in Chelmsford is about 45 minutes, and we usually spend this time discussing the following topics: work, family and friends, health and fitness, something about the car (usually about how many miles there are on the odometer), taxes in the state I am currently living in, gossip about the neighborhood I no longer live in, at least one inappropriate joke, my parents pets, politics, and fishing.

On this particular visit, it seemed important to ask about his new life as a retired person. My dad, it should be known, is a great dad, very supportive, but the guy worked a lotusually up at 5, at work by 6, and often home after dark. Work ethic was big growing up. My mother worked from home as a bookkeeper while raising three lunatic boys (plus every other familys kids from the neighborhood). Phrases like make yourself indispensable, dont leave money on the table, never let them see you sweat, and if youre going to do something, do it right the first time were passed around a lot. Now, however, my dad was someone else entirely, and I was suddenly looking at him as someone different.

In my mind, he was wiser, perhaps with perspective. So I broke off from our usual banter and asked, Hey, Dad, if you could go back and do it again, what advice would you give to a 30-year-old version of yourself? My father, without any hesitation, said two words to me: Work less. My fathers phrase stuck with me. I began thinking about who it is that works harder than all others. We hear crazy stories of people who literally work themselves to death. As I get older and I crest the top of that imaginary slope of life, I am more aware of how finite life isthat there are fewer days left than those Ive already explored.

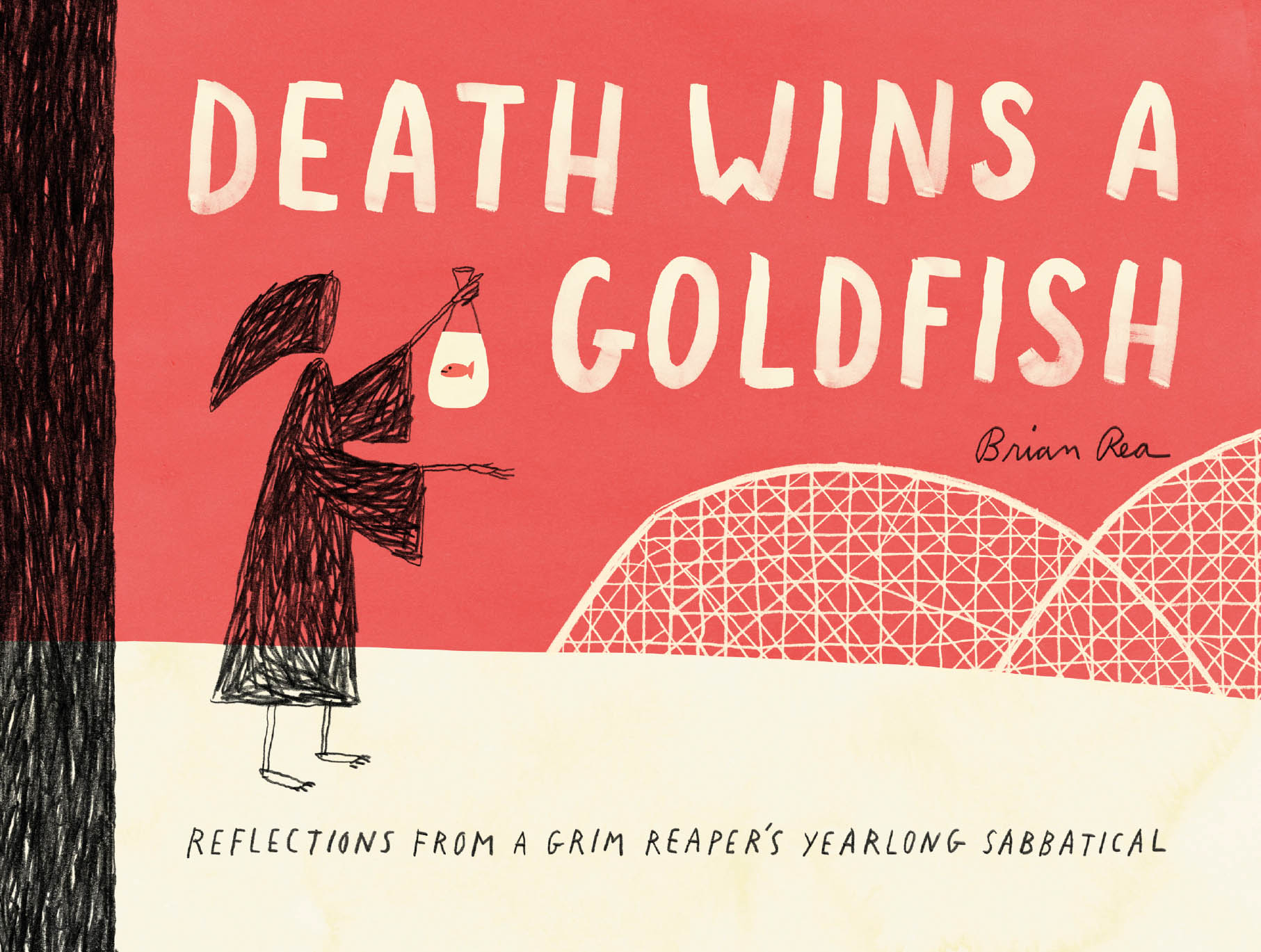

Sad but true. The world death rate has nearly two people dying every second, an insane number to think about. With those kinds of statistics, it might be said that Death works harder than anyone! He never gets a break. But imagine if Human Resources told Death he must take his vacation daysan entire years worth of time off. What would Death do with all that free time? Where would he go? What would his life be like? Would he keep a journal? (Yes.) Would he ever speak? (No.) Over the course of this book, Death never works (i.e., kills anyone). He is, after all, on vacation, and hes doing his best to not work.

There are, of course, other employees plenty busy at Death, Inc., so people do die. Just not at the hands of our friend here. Hes too busy living. Important to note: Death is not one of us. Hes not from this life, so most of the things We the Living do on a daily basis (eating out, dating, social media, manicures, etc.) may be a bit unfamiliar to him. Death has concentrated on one thing only for forever: dying.

So hes perhaps naive to all this living stuff. He does his absolute best to fit in though, and for the most part, he enjoys himself among us. But he ultimately ends up coming to terms with some of the things We the Living are faced with: In particular, when we take a break, were still anxious about the fact that were not working. And thats the dying part. Also important to note: This book is not about dying. True, Death is our hero, but Death Wins a Goldfish could be a book about a banana who works too hard, and it still might convey the same ideas.

Based on the data, though, Death works way harder than bananas do, plus Death serves as a good reminder that there are finish lines to our lifetimes. Last important note: This book is about living. I had a mentor in college, Ron Minard, the former editor of the

Next page

For Miko. Thank you to Bridget Watson Payne, Natalie Butterfield, Allison Weiner, and the rest of the Chronicle team; Leonardo Santamaria for endless assistance; Paul Rogers, Nicholas Blechman, and Paul Sahre for inspiration and friendship; Pablo Delcan for collaboration; mom and dad for inspiring this book; Lucienne Brown for laughter and editorial support; Ron Minard for showing me how to live; the Nilsson family for sharing their island; Mike Rea and Paul Rea for brotherhood; Eric Hoover and Betty Mae Flaherty for believing in me; Uncle Chick for a childhood full of great stories; and Kristina Nilsson for love. Copyright 2019 by Brian Rea. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-4521-7923-0 (epub, mobi) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

For Miko. Thank you to Bridget Watson Payne, Natalie Butterfield, Allison Weiner, and the rest of the Chronicle team; Leonardo Santamaria for endless assistance; Paul Rogers, Nicholas Blechman, and Paul Sahre for inspiration and friendship; Pablo Delcan for collaboration; mom and dad for inspiring this book; Lucienne Brown for laughter and editorial support; Ron Minard for showing me how to live; the Nilsson family for sharing their island; Mike Rea and Paul Rea for brotherhood; Eric Hoover and Betty Mae Flaherty for believing in me; Uncle Chick for a childhood full of great stories; and Kristina Nilsson for love. Copyright 2019 by Brian Rea. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-4521-7923-0 (epub, mobi) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.