Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. - A Social History of Knowledge

Here you can read online Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. - A Social History of Knowledge full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Cambridge;UK, year: 2000, publisher: Polity Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Social History of Knowledge

- Author:

- Publisher:Polity Press

- Genre:

- Year:2000

- City:Cambridge;UK

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Social History of Knowledge: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Social History of Knowledge" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Social History of Knowledge — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Social History of Knowledge" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PETER BURKE

A SOCIAL HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE

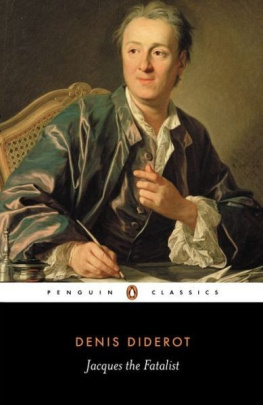

From Gutenberg to Diderot

Based on the first series of Vonhoff Lectures given at the University of Groningen (Netherlands)

POLITY

Copyright Peter Burke 2000

The right of Peter Burke to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2000 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers, a Blackwell Publishing Company.

Reprinted 2002, 2004, 2007, 2008

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burke, Peter.

A social history of knowledge: from Gutenberg to Diderot / Peter Burke.

p. cm.

The Vonhoff lectures, 19989.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-7456-2484-6

ISBN: 978-0-7456-2485-3 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-7456-6592-4 (eBook)

1. Knowledge, Sociology ofHistory. I. Title.

BD175.B86 2000

306.4'2'0903dc21

00039973

Typeset in 10.5 on 12pt Sabon

by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

Printed and bound in United States by Odyssey Press Inc., Gonic, New Hampshire

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk

This book is based at least as much on forty years study of early modern texts as it is on secondary works. The footnotes and bibliography, however, are confined to the works of modern scholars, leaving the primary sources to be discussed in the text itself. Although the focus of the study is on structures and trends rather than on individuals, it is impossible to discuss a topic such as this without introducing hundreds of names, and readers are advised that the dates as well as brief descriptions of each person mentioned in the text will be found in the index.

The study published here is the result of a long-term project which has led to a number of articles as well as to lectures and seminar papers given at Cambridge, Delphi, Leuven, Lund, Oxford, Peking, So Paulo and St Petersburg. After long simmering, the project was finally brought to the boil by the invitation to deliver the first series of Vonhoff lectures at the University of Groningen.

My special thanks to Dick de Boer for looking after me at Groningen and reminding me of the importance of changes in the knowledge system in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Thanks also to Daniel Alexandrov, Alan Baker, Moti Feingold, Halil Inalcik, Alan Macfarlane, Dick Pels, Vadim Volkoff and Jay Winter for help of different kinds, and to Joanna Innes for letting me see her classic though still unpublished paper on the use of information by the British government.

For commenting on parts of the manuscript I am indebted to Chris Bayly, Francisco Bethencourt, Ann Blair, Gregory Blue, Paul Connerton, Brendan Dooley, Florike Egmond, Jos Maria Gonzlez Garca, John Headley, Michael Hunter, Neil Kenny, Christel Lane, Peter Mason, Mark Phillips, John Thompson and Zhang Zilian. My wife Maria Lcia read the whole manuscript and asked some usefully awkward questions as well as suggesting improvements. The book is dedicated to her.

Whatever is known has always seemed systematic, proven, applicable and evident to the knower. Every alien system of knowledge has likewise seemed contradictory, unproven, inapplicable, fanciful or mystical.

Fleck

T ODAY we are living, according to some sociologists at least, in a knowledge society or information society, dominated by professional experts and their scientific methods. Historians of the future may well refer to the period around 2000 as the age of information.

Ironically enough, at the same time that knowledge has entered the limelight in this way, its reliability has been questioned by philosophers and others more and more radically, or at least more and more loudly than before. What we used to think was discovered is now often described as invented or constructed. But at least the philosophers agree with the economists and sociologists in defining our own time in terms of its relation to knowledge.

We should not be too quick to assume that our age is the first to take these questions seriously. The commodification of information is as old as capitalism (discussed in ). The use by governments of systematically collected information about the population is, quite literally, ancient history (ancient Roman and Chinese history in particular). As for scepticism about claims to knowledge, it goes back at least as far as the ancient Greek philosopher Pyrrho of Elis.

The point of these remarks is not to replace a crude theory of revolution with an equally crude theory of continuity. A major aim of this book is to try to define the peculiarities of the present more precisely by viewing it in the perspective of trends over the long term. Current debates have often stimulated historians to ask new questions about the past. In the 1920s, growing inflation encouraged the rise of price history. In the 1950s and 1960s, a population explosion encouraged research into demographic history. In the 1990s, there was increasing interest in the history of knowledge and information.

From the knowledge element in society let us turn to the complementary opposite theme of the social element in knowledge. One purpose of this book may be described in a single word: defamiliarization. The hope is to achieve what the Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky described as ostranenie, a kind of distanciation which makes what was familiar appear strange and what was natural seem arbitrary.

The suggestion that what individuals believe to be truth or knowledge is influenced, if not determined, by their social milieu is not a new one. In the early modern period to mention only three famous examples Francis Bacons image of the idols of the tribe, cave, market-place and theatre, Giambattista Vicos remarks on the conceit of nations (in other words, ethnocentrism) and Charles de Montesquieus study of the relation between the laws of different countries and their climates and political systems all expressed this fundamental insight in different ways which will be discussed in more detail below (210). All the same, the shift from insight to organized and systematic study is often a difficult one which may take centuries to accomplish. This was certainly the case for what is now described as the sociology of knowledge.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Social History of Knowledge»

Look at similar books to A Social History of Knowledge. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Social History of Knowledge and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.