Contents

To my husband, Richard, and my children, Tommaso and Francesca, who fill my life with a reassuring sense of belonging within a cosmos kept afloat and spinning by the ever-present sunlight of their love

Copyright 2018 by Ingrid Rossellini

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Cover design by John A. Fontana

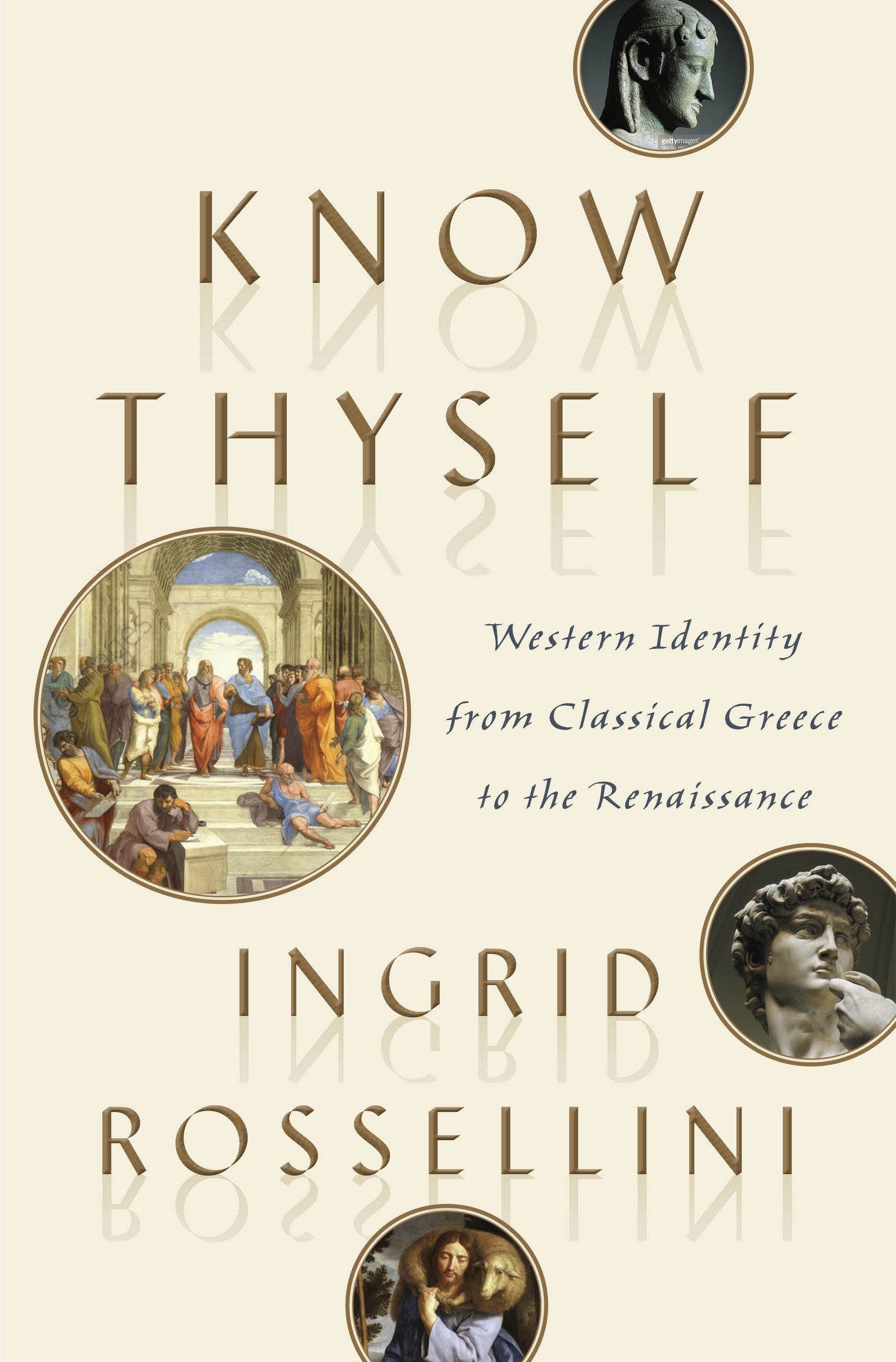

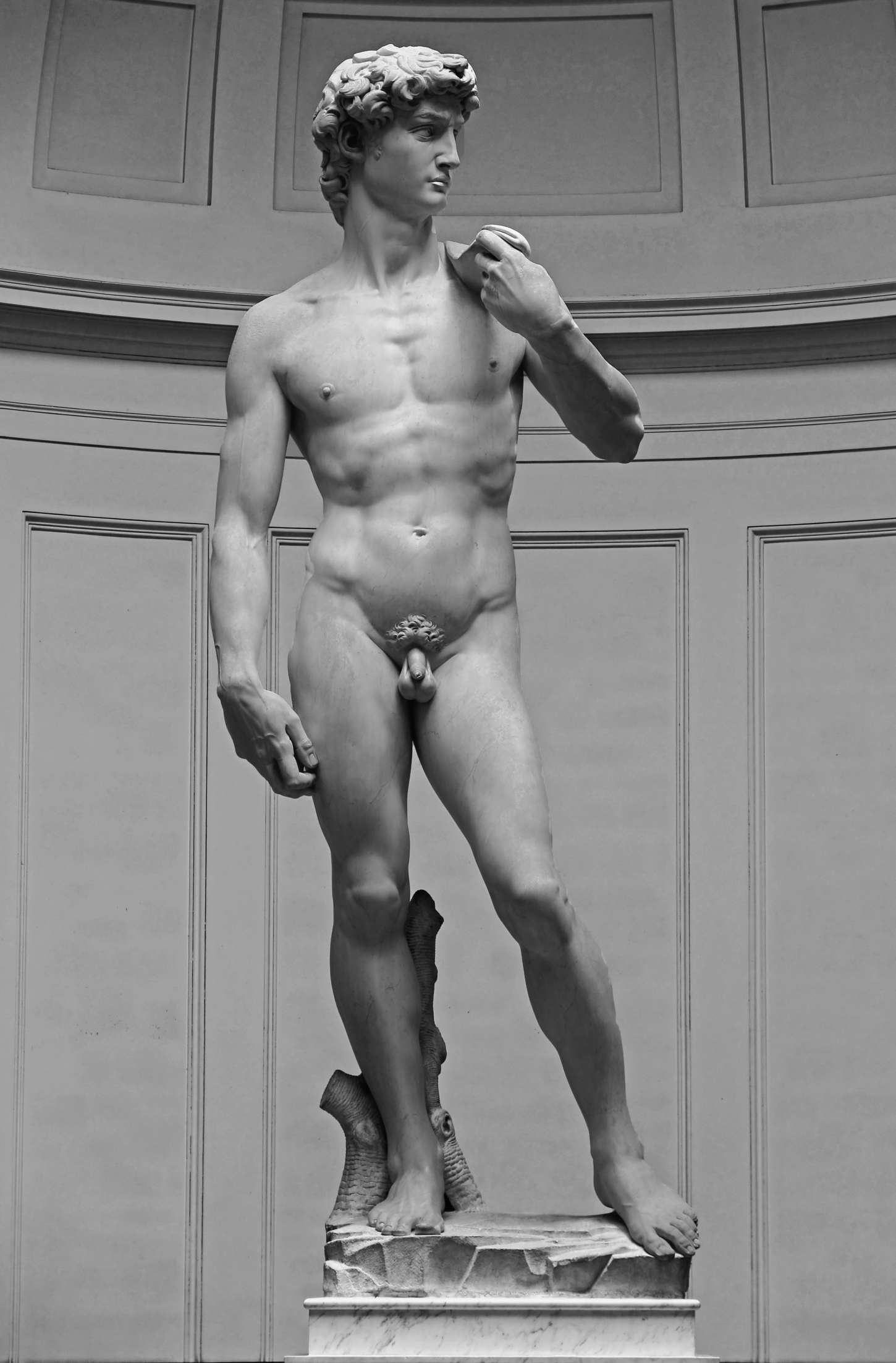

Cover images: (details, clockwise, left) The School of Athens by Raphael, akg-images; Piraeus Apollo, 530 B.C. , De Agostini/Getty Images; David by Michelangelo, Alinari/Art Resource, N.Y.; The Good Shepherd by Philippe de Champaigne, SuperStock

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rossellini, Ingrid, author.

Title: Know Thyself : Western identity from classical Greece to the Renaissance / by Ingrid Rossellini.

Description: First edition | New York : Doubleday, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017045163 |

ISBN 9780385541886 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385541893 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Civilization, WesternHistory. | Religion and civilizationHistory. | Philosophy and civilizationHistory. | Identity (Philosophical concept)

Classification: LCC CB245 .R6625 2018 | DDC 909/.09821dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045163

Ebook ISBN9780385541893

v5.3_r1.1

a

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Who are you?

If someone asked that question today, most people would offer answers that, aside from general references to gender, nationality, and ethnicity, would essentially focus on their personal characteristics, choices, and preferences. The common assumption is that the individual self is a fully autonomous and original entity, capable of selecting whatever path he or she decides to entertain in a way that is completely independent from traditional views and expectations. Individual identity, as we conceptualize it today, is something like a kit whose parts can be chosen, styled, and assembled at will: a do-it-yourself enterprise.

Although that is for the most part true, psychologists never fail to remind us that what we experienced as children remains an essential factor in the shaping of our adult selves. In order to understand our present, we need to revisit our past. The same thing could be said about our collective history: understanding who we were remains an essential component in understanding who we are today.

Do I mean to imply that Know Thyself is a sort of psychological guide to a more rewarding and fulfilling relation with our true selves? Yes, in fact, but definitely not in a conventional way. What I mean is that this is not a book about psychology but a book about history with a psychological slant: in other words, a book that, besides describing crucial moments of history from Greek antiquity to the Renaissance, highlights how the different definitions that the self has received contributed to the creation of the values and ideals that, down the centuries, have shaped and motivated the choices and actions of people and the makeup of their society.

In choosing this particular lens for observation, I was inspired by the nineteenth-century French historian Fustel de Coulanges, who claimed that recollecting facts is an insufficient way to look at history without an equal focus on the nature and development of the human personality. What that perspective reveals is that history is a complex tapestry woven from actual events but also from the narratives that we humans have imposed upon those facts to try to make sense of ourselves and our reality.

This book is meant to be not an academic treatise but a guide addressed to the lay reader who, while genuinely curious to explore the past, often feels intimidated by the excessive complexity of scholarly studies. Things have only gotten worse in these last decades: because as the disciplines we generally label humanities have become increasingly neglected in our academic curricula, understanding earlier ways of thinking has become, for many, ever more difficult and frustrating.

To try to remedy that confusion and make this book as clear and accessible as possible, I chose to avoid the over-detailed style typical of specialized approaches, to offer instead an interdisciplinary overview that, although simplified, still provides a comprehensive map of major patterns of history and culture. To clarify the discussion, I have also included many references to the visual arts. This choice is based on the fact that for thousands of yearsat least until the invention of the printing press, in the middle of the fifteenth centuryvisual art was the only available means of mass communication capable of conveying, to a population that was largely illiterate, the models of excellence that the political, philosophical, and/or religious ideology of the times considered best fitted to exemplify what a human being was expected to be.

An important theme that we will explore while looking at the ideals that different epochs nurtured concerns the recurrent creation of legendary and mythical factsthe narratives that, for the sake of inspiration, tradition fostered with an intensity that often appears much too exuberant for the rigorous test of credibility as Joseph Campbell indicated when he wrote that a myth is something that has never happened, and is happening all the time.

To begin, let me bring you back to Delphi of ancient Greece, where people went to consult the oracle of Apollo: the Greek god of reason who was also the only pagan divinity who appeared willing to respond to the people who came to seek his advice.

I use the verb to appear because how Apollos oracle worked was more ambiguous than revelatory, in the sense that rather than offering clear guidance, it only provided cryptic hints and scattered pieces of information. These were as confusing and indirect as the language of his messengerthe priestess, called Pythia, who in delirious fits of trance channeled the voice of Apollo, by whom she claimed to be possessed. The paradox of the oracle was that because it forced people to interpret the vagueness of those utterances, the ball was implicitly returned right back to those who sought its guidance. That way, rather than having the god clearly telling them what to do, people were indirectly led to use their own intellectual faculties to come up with the answers best fitted for their particular challenges and problems.

The key to that clever strategy was expressed in the motto etched at the top of Apollos temple: Know thyself. The dictum essentially meant this: because the meaning you give to your life is what propels your actions, before asking whatto do, ask yourself who you are.

This was (and is) by no means an easy endeavor, as proven by the endlessly varied answers that we humans have come up with all along the centuries.

Take our modern view of identity, for example. To encourage self-awareness in a child, we say, discover the talents and qualities that make