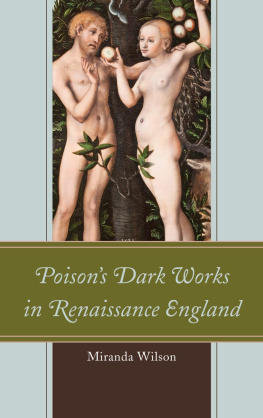

Sherman - Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England

Here you can read online Sherman - Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Anglaterra;Philadelphia;Pa, year: 2008, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Pennsylvania Press

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- City:Anglaterra;Philadelphia;Pa

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Used Books

MATERIAL TEXTS

Series Editors

Roger Chartier

Joan DeJean

Joseph Farrell

Anthony Grafton

Janice Radway

Peter Stallybrass

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Used Books

Marking Readers in Renaissance England

WILLIAM H. SHERMAN

Copyright 2008 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044112

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN-13: 978-0-8122-4043-6

ISBN-10: 0-8122-4043-X

For Claire, my ideal reader

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

In 1985, Roger Stoddard published his seminal catalogue, Marks in Books, Illustrated and Explained, and his opening sentences set an agenda that has challenged a generation of scholars, librarians, conservators, and collectors: When we handle books sensitively, observing them closely so as to learn as much as we can from them, we discover a thousand little mysteries.... In and around, beneath and across them we may find traces... that could teach us a lot if we could make them out.

My own work in this field began with a famous (or rather infamous) reader, the Elizabethan polymath John Dee. But there has been a pressing need for bigger pictures and broader brush-strokes. Jonathan Roses frustrations are typical among recent reviewers of work in this field:

While this book makes no claim to a disciplinary epiphany, it is the product of many eureka moments; and the isolated traces upon which it rests do yield some larger patterns and a more systematic sense of how a wider group of readers used a wider range of books than in previous accounts of pre-modern marginalia.

In pursuit of a preliminary database for such an overview, I carried out a reasonably comprehensive survey of one of the worlds major repositories of English Renaissance booksthe more than 7,500 volumes printed between 1475 and 1640 that make up the so-called STC collection at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. I have since conducted a similar study of the much smaller but no less interesting collection of books and manuscripts created by Archbishop Matthew Parker and bequeathed to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (where it is now housed in the library bearing his name); and I have followed up these systematic surveys with smaller-scale studies of other readers and materials in a number of collections on both sides of the Atlantic.

Like other scholars who have caught the marginalia bug, I have been astonished by the sheer volume of notes produced by early readers. More than one in five of the Huntingtons early printed books preserve the notes of early readers (and for certain subjects and in certain decades the proportion is far higher), and the annotations in many books from the Rosenthal collection are so thorough they threaten to overwhelm the text: one extraordinary copy of Aristotles Posterior Analytics, printed in Leipzig circa 1500, has some 59,600 words of annotation on its 68 pages; and the nearly 50,000 words of marginalia in a 1516 Bible are limited to only 41 pages (producing a tally of more than 1,200 manuscript words per page), where they are often found piled three or four deep between lines of the printed text.lives of their readers that we have only begun to explore, and it is the primary purpose of this book to make the marks of Renaissance readers more visible and legible to new and experienced scholars alike.

Anyone who turns to marginalia with high hopes of easy answers quickly discovers that the evidence they contain turns out to be (if not always thin, scattered, and ambiguous) peculiarly difficult to locate, decipher, and interpret. As this book took shape I found myself not only gathering stories about specific readers and readings but also grappling with a series of methodological problemsand throughout this book I will keep one eye on what we can learn from readers marks and another on what we need to learn, unlearn, and relearn in order to do so. As I will explain in more detail in

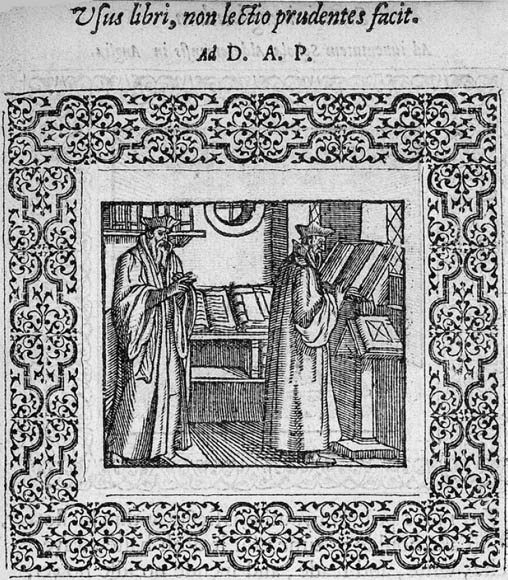

As for reading, I have comelike Bradin Cormack and Carla Mazzioto prefer the language of use.):

The volumes great, who so doth still peruse,

And dailie turnes, and gazeth on the same,

If that the fruicte thereof, he do not vse,

He reapes but toile, and never gaineth fame:

First reade, then marke, then practise that is good,

For without use, we drinke but LETHE flood.

Figure 1. The use, not the reading, of books makes us wise, from Geoffrey Whitneys Choice of Emblems (1586). By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

I am partly acknowledging the fact that not all of the uses to which books can be put should be described as reading. I am also trying to avoid that words associations with particular protocols and etiquettesincluding privacy, linearity, and cleanliness. I am endorsing Stoddards suggestion that textual scholars must also be anthropologists and archaeologists, putting books alongside the other objects that can help us to reconstruct the material, mental, and cultural worlds of our forebears: traces of wear can tell us how artifacts were used by human And, finally, I am attempting to take us closer to the Renaissance periods own surprisingly rich vocabulary for book use (in which the word use is itself crucialas Whitneys emblem suggests and as we shall see in virtually every chapter below).

One of Gabriel Harveys elaborate and self-reflexive marginal notes in his copy of Peter Ramuss conomia will suffice to suggest that modern readers and scholars of reading have lost some of the scope and sophistication of the Renaissance periods framework (linguistic, conceptual, and technical) for using books:

This whole booke, written & printed, of continual & perpetual use: & therefore continually, and perpetually to be meditated, practiced, and incorporated into my boddy, & sowle.

In A serious & practicable Studdy, better any on[e] chapter, perfectly & thorowghly digested, for praesent practis, as occasion shall requier: then A whole volume, greedily deuowrid, & rawly concoctid....

No sufficient, or hable furniture, gotten by unperfect posting, or superficial overrunning: or halfelearning: but by perpetual meditations, repetitions, recognitions, recapitulations, reiterations, and ostentations of most practicable points, sounde and deepe imprinting as well in ye memory, as in the understanding: for praegnant & curious reddines, at euery le[a]st occasion. Every Rule of value, and euery poynt of vse, woold be continually recognised, and perpetually eternised in your witt, & memory.

The Elizabethans evidently had as many words for reading as the proverbial Eskimo has for snow.

In an essay on reading practices in ancient Greece, Simon Goldhill has called for a Literary History without Literature. He objects to the destructive poverty of the category of literature for the way in which the critical engagement with language production and consumption functions in the ancient world. The establishment of the sphere of the literary with its various exclusions does not merely distort the interconnections between the texts of poetry, say, and the other textual productions of the ancient world, but also thoroughly twists the connections between those texts and the culture in which and for which they were produced. To the extent that the same can be said for reading, perhaps it is time to call for a history of reading without reading?

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England»

Look at similar books to Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Used books: marking readers in Renaissance England and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.