Acknowledgments

This book owes its existence to the contributions of many. Well before the seeds of this project were sown, a graduate seminar on Montaigne offered by the late Grard Defaux at the Johns Hopkins University in 2000 transformed me (at least in my hopes) into a student of sixteenth-century French literature and culture. To all those colleagues who offered me their thoughts and comments in Baltimore, Cambridge, Paris, and Los Angeles during the past three years, I would like to extend my warmest gratitude: Tom Conley read the entire manuscript and has often contributed to the ideas presented in it; Jean-Claude Carron, David Laguardia, Frank Lestringant, and Kathleen P. Long have given me invaluable feedback on one or many aspects of this work. Exchanging ideas about theology and the scandal with Hent de Vries and Burcht Pranger has inspired me in many places in this book. Mihly Balzs, Ivn Horvth, and Levente Self suggested parallels in an East-Central European context and have reminded me that the implications of this book do not stop at the borders of early modern France. I thank Stephen Nichols for his invitation that allowed me to present an early version of Chapter 2 at a conference at Stanford University in 2007, and I thank the audience for their useful comments. In addition, I am keenly aware of the support of my colleagues at the University of Southern California. I thank in particular Peggy Kamuf, Alexandra Isfahani-Hammond, Rebecca Lemon, Peter Mancall, Claudia Moatti, Natania Meeker, Panivog Norindr, Karen Pinkus, Tita Rosenthal, and Bruce Smith for their collegial and professional generosity.

The final draft of this project was completed while in residence at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard University. The Radcliffe Institute provided conditions for research and writing during the year of 20062007 that were nothing less than ideal, but the heart of the program was the people. Let me mention only a few names, for whose friendship and conversations I am very thankful: Elizabeth Bradley, Giovanni Capoccia, Bridgit Doherty, Major Jackson, Ranjana Khanna, William McFeely, Nancy Shepherd-Hughes, Anna Schuleit, and Marie-France Vigneras.

A grant from the Zumberge Research Fund at the University of Southern California allowed me to carry out archival work in Paris. I also thank the College of Arts and Sciences at USC for its generous support of the publication of this book.

I dedicate it to my mother, va Szab, and father, Istvn Szabari, for their truly boundless love, embracing the distance of continents.

Conclusion

The authors of the Satyre Menippee imagine the utopian possibility of readers expressing their political differences through additions to the pamphlet, thus turning the new literary form of menippean satire into a tool for voicing, enacting, and defusing irreconcilable differences of view that call into question the monarchys politics of reconciliation after the consolidation of political power. Although the absolutist monarchy sought to curb polemical literature as a dangerous speech act that could revive the memory and the disastrous effect of past injuries and destabilize social order, satire continued to attract the interest of collectors who saw in it a diversion conducive to moral reflection, available to those who were able to withdraw from the political arena. As we have seen in Pierre lEstoiles journals, paradoxically, these writers and journalists turn satire into the very tool of this withdrawal by the end of the century.

How important was the literary and imaginary dimension of vituperation for the emergence of a political genre? The humanistic practices that often lie at the roots of polemical literature, or to which authors and creators of polemical literature refer, are rhetorical devices of distancing and reflection. When simplified and manipulated, these devices can be used to draw audiences all the more into an ideology, into a group whose members know. However, they can also be used to distance them from views that are being propagated in the political arena, on the street, in the church, and on the public square. The vivid images that project these communities do not fade even when the causes that have animated them do. Studying the literature of vituperation in sixteenth-century France teraches us that the power of words and symbols lingers beyond the social and political circumstances of their publication.

The images that bespeak a vital political imagination in these pamphlets constitute a robust and oft-revisited quarry in French history. The Satyre Menippee was reprinted countless times with notes and supporting documents in the course of the eighteenth century, while lEstoiles journals were printed in digest fashion under the title Memoires pour servir lhistoire de France (1719). Just prior to the revolution, these books were used to attack the church and the state. Eighteenth-century editions of the Satyre Menippee often helped foster distrust in the Catholic clergy, in the Jesuits, and in devout Catholic practices and rites. In addition, they also contributed to the gradual corrosion of the sacred power of the absolutist state that relied on these rites and on an alliance with the church.

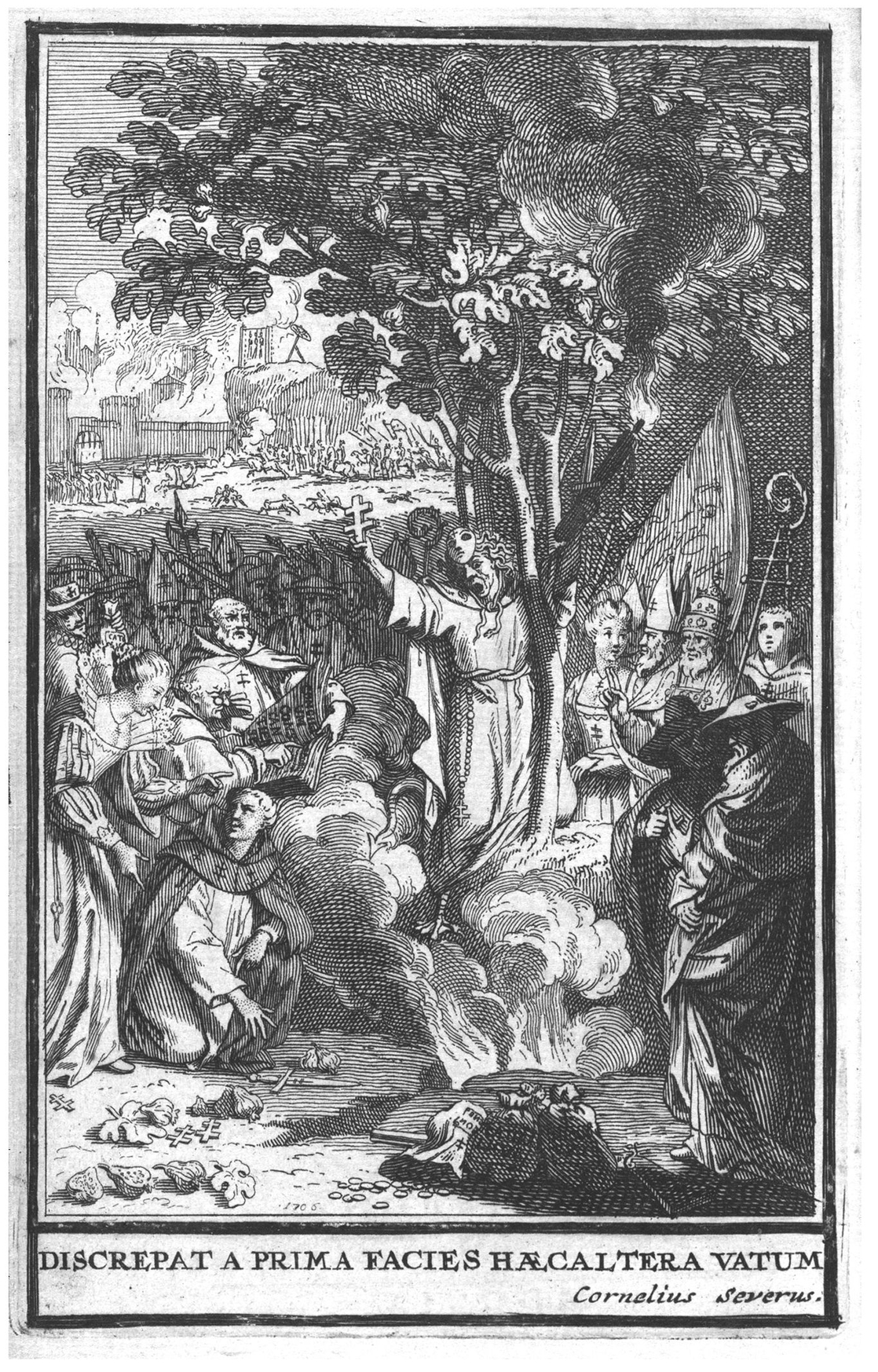

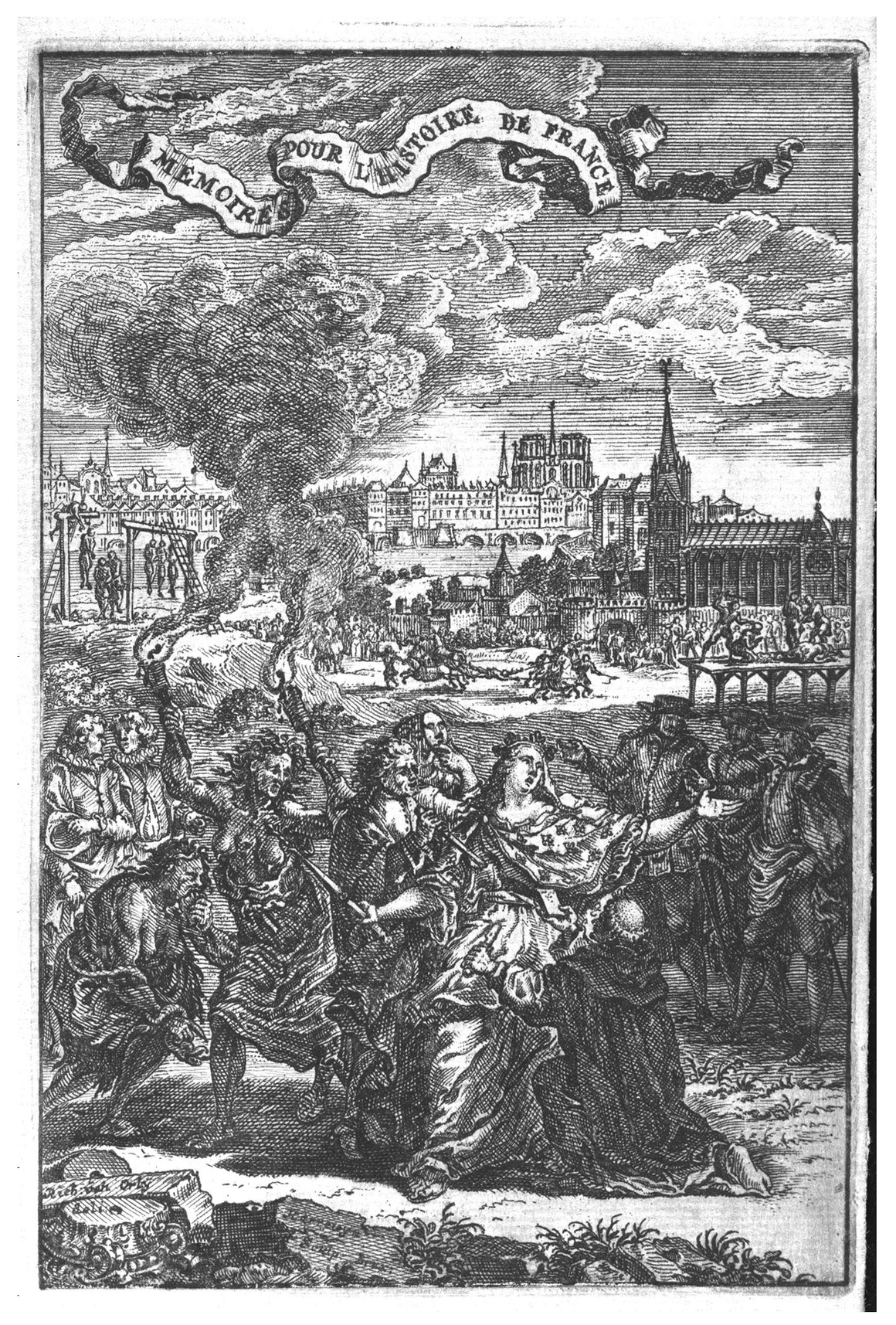

Another image, this one appearing in the Memoires pour servir lhistoire de France , also reactivates the clichs of the past. It shows Madame Montpensier in the center of a gathering of frenzied women (reminiscent of the Furies) with torches, one of whom has a snake twisted around her arm; Jacques Clment kneels in a supplicating pose in front of Madame Montpensier, and a clerical figure with disheveled hair eggs her on ( The re-emergence of the satirical and vituperative models of the sixteenth century show that they were deemed highly useful and that the sixteenth-century satirists had created enduring themes and models of religious and political discourse compelling to later generations caught up in their own struggles for identity and power. Not only individual readers or communities but whole societies can get taken in by the scandalous rhetoric of religious and political satire and its effects, and the French society of the ancien rgime became caught in that which lEstoile aptly terms libert franoise .

. Madame de Montpensier. [Le Roy, Jean, and others], Satyre Menippee (Rouen, 1709). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard College Library, *FC5.Sa836.1709.

. Madame de Montpensier. Memoires pour servir lhistoire de France (Cologne, 1719). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard College Library, *FC5.L5675.719m.

Notes

I did not modernize the orthography of sixteenth-century titles either here or in the bibliography. I standardized and modernized the names of authors when necessary. Works whose authorship is unknown appear as anonymous, except in cases where there exists a strong consensus in the academic community about the authors identity. I listed these titles under the probable or conjectured name in brackets.

Introduction

The simplest form of this verbal pleasure consists in neologisms, linguistic innovation, and verbal wit. Claude Postels recent historical overview of polemical works in sixteenth-century France provides a glossary of useful terms from abominable (abominable) to vulpin (foxlike). See Claude Postel, Trait des invectives au temps de la Rforme (Paris: Belles Lettres, 2004). The first reader to draw attention to verbal wit in polemical literature was Lazare Sainan, the Romanian Romance philologist with a special interest in linguistic creativity in French (his adopted culture). Sainan discovered the influence of Rabelaisian vocabulary in works by Henri Estienne, Calvin, Guillaume Postel, and in works such as the Satyres chrestiennes de la cuisine papale , LIsle des hermaphrodites , and the journals of Pierre de lEstoile. See Linfluence et la rputation de Rabelais (Paris: J. Gamber, 1930), 186212.