Performance and American Cultures

General Editors: Stephanie Batiste, Robin Bernstein, and Brian Herrera

This book series harnesses American studies and performance series and directs them toward each other, publishing books that use performance to think historically.

The Art of Confession: The Performance of Self from Robert Lowell to Reality TV

Christopher Grobe

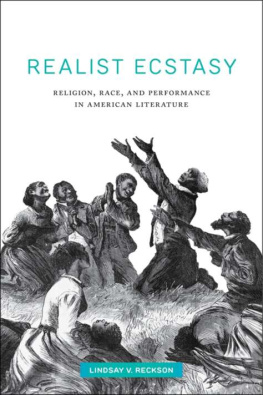

Realist Ecstasy: Religion, Race, and Performance in American Literature

Lindsay V. Reckson

Realist Ecstasy

Religion, Race, and Performance in American Literature

Lindsay V. Reckson

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2020 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Reckson, Lindsay Vail, 1982 author.

Title: Realist ecstasy : religion, race, and performance in American literature / Lindsay V. Reckson.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2019] | Series: Performance and American cultures | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Realist Ecstasy explores religion, race, and performance in American literatureProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019015753 | ISBN 9781479803323 (cloth) | ISBN 9781479850365 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: American literatureHistory and criticism. | Realism in literature. | Religion in literature. | Race in literature. | Performance in literature.

Classification: LCC PS169.R43 R43 2019 | DDC 810.9/12dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015753

for Ben, Ada, and Maxine

Contents

Being Beside

What does Jim Crow secularism feel like?

If Cranes novella gestures in this scene to some occluded or indefinable link between racial violence and spiritualized performance, the second moment I offerfrom Charles W. Chesnutts 1901 novel The Marrow of Tradition, a fictionalized account of the Wilmington race riot of 1898is more direct in its depiction of white supremacy as a haunted affair. Describing the efforts of the prominent newspaper owner Major Carteret and his compatriots to manifest white fears of a miscegenated voting bloc (embodied in the Fusion party), The Marrow of Tradition invokes the popular racist imaginary of African American men as figures of supernatural rapaciousness: It remained for Carteret and his friends to discover, with inspiration from whatever supernatural source the discriminating reader may elect, that the darker race, docile by instinct, humble by training, patiently waiting upon its as yet uncertain destiny, was an incubus, a corpse chained to the body politic, and that the negro vote was a source of danger to the state, no matter how cast or by whom directed. As the discriminating reader of Chesnutts realism is meant to understand, and as the novel attests with deep irony, the response to such a perceived threat is to produce more and more corpsesCarteret and his friends quickly spread their supernatural inspiration, inaugurating a devastating outbreak of white supremacist violence in its name.

While strikingly different in their idioms, each of these moments belongs to the affective life of Jim Crow secularism, and to its bodily dramas of ritual (dis)possession, compulsion, inspiration, and contagious enthusiasm. Collectively, I call such dramas realist ecstasy, a deliberate contradiction in terms that this book aims not to resolve, but to hold in This unsettling, transfixing, spellbinding persistence of the unintelligiblecirculating in dynamic ways through realisms taxonomic enthusiasms, its broadscale effort to forge sense out of a turbulent social sceneis at least part, I want to suggest, of what Jim Crow secularism feels like.

In ecstasy, the body-in-motions capacity to function as a stable referent is utterly at stake, and it is the contest over the meaning of such restless bodies to which Realist Ecstasy most often attends. Such bodies are by no means always a disruptive force; indeed, I argue that it is in part through its ecstatic sequences that realism habitually constructs and naturalizes a secular order that understands religious and racial difference in tandem, evincing a hegemonic regime of white liberal Protestantism Invoking the incubus of the white supremacist imaginary, The Marrow of Tradition recognizes this grammarwhich gives race a supernatural explanatory power and deems religion rational or irrational depending on its proximity to Christianity and to whitenessas central to a regime predicated on the economic and political disenfranchisement of African Americans. But it also reverses that foundational script, insisting that whiteness constructs and reinforces itself through a fanatical investment in the supernatural (and material) reality of race. This violent form of inspiration is what W. E. B. Du Bois would later call a new religion of whiteness; as we will see, Du Bois pointedly aligns whiteness and fanaticism at a moment when what constituted religion as such became utterly central to the global and imperial formations of secular modernityformations that, Chesnutt and Du Bois recognize, were themselves deeply haunted.

Drawing a different kind of inspiration from such texts, this book describes post-Reconstruction realism as a set of performances that insist on the presence of the past and its ongoing if occluded impact within the social field that realism purports to describe. Focusing on realism as it emerges specifically in the context of the Reconstructions abandonment and the consolidation of Jim Crow regimes of racial personhood allows us to understand post-Reconstruction as itself a haunted structure, less a periodizing description than an analytic for realisms complex historicity. In approaching realism as a form of hauntology, I draw from Avery Gordons account of haunting as a way of knowingand, indeed, feelingthe persistence of violent structures that, within the regime of secular-linear time, might appear as largely overcome. Ecstasy, I argue, is one of the ways in which such haunting emerges from within the affective life of Jim Crow.

With its dramas of possessionof bodies caught, seized, or compelled by the Spiritecstasy bespeaks the lingering question of black freedom in the aftermath of Reconstruction. It thus belongs to what Saidiya Hartman has described as the intimate proximity between liberty and bondage under Jim Crow, a regime of subjection that made it impossible to envision freedom independent of constraint or personhood and autonomy separate from the sanctity of property. The fact that these possibilities exist alongside one another is fundamental to ecstasys undecidabilityand thus to its realism.

Secular Affects, Realist Repertoires

Realist Ecstasy argues that the post-Reconstruction consolidation of racial apartheid must be understood as part ofindeed, central toa more diffuse but no less powerfully regulatory regime of secularism. In gleaning the affective life of Jim Crow secularism, I draw on the work of scholars from a range of disciplines who have asked (with Ann Pellegrini), What does secularism feel like? Similarly, such an ongoing excavation unsettles our capacity as scholars to confidently stand apart from such formations, or to securely narrate their histories via the supposedly linear unfolding of secular time.

Next page