Zoé Oldenbourg - Massacre At Montségur

Here you can read online Zoé Oldenbourg - Massacre At Montségur full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: The Orion Publishing Group Ltd, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Massacre At Montségur

- Author:

- Publisher:The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Massacre At Montségur: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Massacre At Montségur" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Massacre At Montségur — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Massacre At Montségur" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MASSACRE AT

MONTSGUR

Zo Oldenbourg

CONTENTS

The anglicization of mediaeval French names always presents some difficulty: I cannot claim to have been consistent in this respect. The better-known names I have converted according to traditional English usageas, for example, in Sir Steven Runcimans The Mediaeval Manichee. Elsewhere I have been somewhat arbitrary, and acted as the context seemed to demand in terms of euphony or convenience: thus, variously, William de Puylaurens, [Pierre des] Vaux de Cernay (where Sir Steven reads Peter de Vaux-Cernay), Peter Amiel, or Blanche of Castille. I trust that readers will take this captious attitude in the spirit with which T. E. Lawrence treated the proof-reader of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

I would like to express my thanks publicly to Mme Oldenbourg for reading my entire typescript with scrupulous care, saving me from several egregious errors, and on occasion putting me to shame by suggesting a better English phrase than I could have thought of myself. It is a rare pleasure for a translator to be blessed with so amiable and co-operative an author.

PETER GREEN

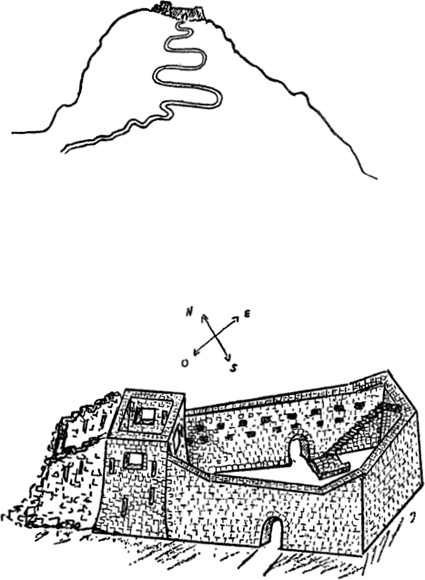

Diagrammatic sketch of the fortress of Montsgur with the road leading up to it

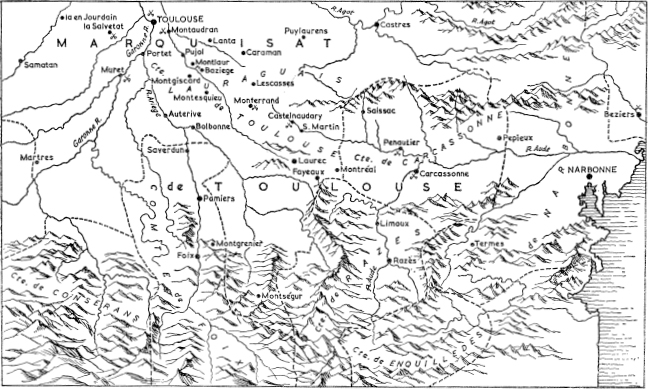

THE GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND OF THE ALBIGENSIAN CRUSADE

ON 10TH MARCH 1208 His Holiness Pope Innocent III issued a solemn call to arms, summoning all Christian nations to launch a Crusade against a country of fellow-Christians. This Crusade, he claimed, was not only justifiable but a matter of dire necessity; the heretics who inhabited this land were worse than the very Saracens.

The Popes appeal came four years after the capture of Constantinople by a Crusaders army. The new enemy was Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, a cousin of the King of France and brother-in-law to the Kings both of England and of Aragon. Besides being bound by ties of homage to these three monarchs he owed a similar allegiance to the German Emperor; he was, further, Duke of Narbonne, Marquis of South-West Provence, a feudal sovereign whose authority extended over the regions of Agenais, Quercy, Rouergue, Albigeois, Comminges and Carcasss, not to mention the County of Foix. He was, in short, one of the greatest princes in Western Christendom, premier baron of all the territories where the langue doc was spoken.

Since this was a period when actual power was firmly in the hands of the nobility, and since this nobility, from the monarch down to the smallest landed proprietor, was by definition a military caste, it follows that war achieved a permanent, necessary status in their lives. Christian princes were never short of an excuse for invading their neighbours territories. But the preceding century had seen, first a slackening, then a sharp falling off in that enormous enthusiasm with which Western Europe had hitherto regarded the Holy Land. In the hey-day of the twelfth century, the warrior-pilgrim, though he might frequently be pursuing material ends, felt confident that he was fighting on Gods behalf. But the nobility, their ranks decimated on the battlefields of Palestine, chafed bitterly against the useless sacrifices they were called upon to make, while the various local campaigns they had to conduct struck them as being both petty and dull.

Later, at the time of the Fourth Crusade, Simon de Montfort (a warrior whose appetite for warfare even the most sceptical could hardly question) was to refuse flatly to bear arms against a Christian city, or to put himself in the Doges service rather than that of the Pope. Even though the bulk of the Crusaders failed to copy his example, and followed up their capture of Catholic Zara with an assault on Constantinople, nevertheless the scandal occasioned by this deflection of a Crusade from its true goal left the French nobility with a certain feeling of disillusion, despite the perennially powerful lure of conquest and pillage. The Crusade itself was gradually becoming a dead end, and the Holy Land, increasingly threatened though it was, now attracted only a minority of enthusiasts. For a good many knights and men-at-arms this way of obtaining Gods forgiveness (which allowed them to cover themselves with glory on the battlefield as well) had become an habitual practice. Sometimes genuine passion inspired it; more often the motive was material need.

What are we to make of this new type of Crusade, imposed upon Christendom by the Popes emergency decree? One factor we should bear in mind is how cosmopolitan in their connections the aristocracy of this period were. In England the nobles all spoke French. Italian and Spanish poets were composing in the langue doc, and German Minnesinger took lessons from the Troubadours. Above all, the intricate and complex ties created by feudal obligations, coupled with a whole network of political intermarriage, had ensured that all the great princes throughout Western Christendom were mutually bound by responsibilities of vassalship, or kinship, or both. In such conditions it is hard to see how a Holy War preached against the Count of Toulouse ever reached the point of actually being fought.

When, on this March day in 1208, Romes Bull of Anathema was flung down on the soil of Languedoc, it cut the history of Catholic Christendom clean in two. The Papal sanction granted to a war conducted against a Christian people was to destroy, for ever, the moral authority of the Church, and to undermine the very foundations on which that authority rested. What the Pope regarded as a mere casual police action, dictated by particular circumstances, was soon to grow, under the pressure of events, into a methodical system of oppression; and for millions of Western Christians Rome was to become an object of hatred and contempt.

The circumstances which led Innocent III to take such severe action against the Count of Toulouse suggest, a priori, some justification for the Popes appeal. Every single district throughout the Counts domains was a hotbed of heresy; and on 14th January 1208 Brother Peter of Castelnau, the Papal Legate, had been assassinated at Saint-Gilles by one of Raymond VIs officers.

The murder of a Legatethat is, of the Popes Ambassador and Envoy Plenipotentiarywas a capital crime, which fully justified a declaration of war. But the Church was not, in theory, a temporal power, and so could only answer this bloody affront with chastisement of a spiritual order. Nevertheless, such spiritual sanctions were formidable enough. Faced with a threat of excommunication or interdiction kings would at once yield, making chaos of their political alliances or private lives in order to avoid the Churchs thunderbolts.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

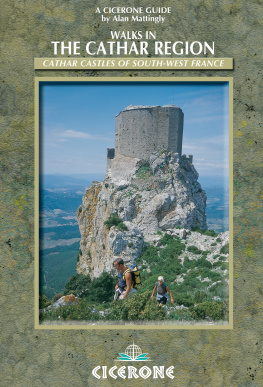

Similar books «Massacre At Montségur»

Look at similar books to Massacre At Montségur. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Massacre At Montségur and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.