Early China c. 2000 BCE206 BCE

This book has come out of a long fascination with China which began in my schooldays in Manchester with A. C. Grahams Poems of the Late Tang, one of those books that opened a window on a world one could never have dreamed existed. Later, as a graduate student in Oxford, sharing a house with a sinologist was another eye-opening time, encountering revelatory books like Arthur Waleys Book of Songs. At that time among the larger-than-life characters who came through our kitchen was David Hawkes, who had been in Tiananmen Square on 1 October 1949 when the Peoples Republic was founded, and who had latterly given up his post as professor of Chinese in order to translate the novel of the millennium, Dream of the Red Chamber (a book whose story is told below, ). Since then my journeys in China have extended over four decades, both as a traveller and as a broadcaster; for example making The Story of China films, which have been seen worldwide, then in 2018 a series on the fortieth anniversary of Deng Xiaopings Reform and Opening Up, one of the most significant events in modern history. Most recently, in autumn 2019, I returned to make a film on Chinas greatest poet, Du Fu, which, though late in the writing of this book, gave me another opportunity to think about the long vistas of Chinese culture and its enduring ideals. We filmed in Chengdu, where Du Fu stayed for nearly four years from the end of 759. Today the supposed site of his Thatched Cottage is one of Chinas most delightful and popular tourist destinations, with its ornamental streams and gardens, stands of bamboo, peach and plum trees, and yellow splashes of wintersweet and jasmine. Its reconstructed buildings, pavilions and gift shops the visitor might think are a purely invented past; but recently, following a chance find during the laying of a drain, an excavation inside the tourist site uncovered the footings of a small Tang dynasty Buddhist monastery, with houses and brick platforms just as Du Fu describes; an inscription on a tablet from 687 even mentions the small tower of the senior monk, evidently the same building west of the stream to which Du Fu refers as the tower of monk Huang. With Tang dynasty ceramics and domestic pottery, eaves tiles and stamped bricks, the find confirms in detail a tradition passed down tenaciously over more than 1,200 years. Though destroyed and rebuilt many times, this was indeed the very spot. Nothing now survives above ground that is of any antiquity, but in China it is not the physical fabric of the building that matters; it is the sense of place that conjures the stories, songs and poems that have been handed down for so long among the people; the riches of what Confucius called this culture of ours.

Writing on Chinas past, though, is a daunting task, all the more so if one is not a sinologist. China is a huge and incredibly rich, indeed inexhaustible, subject the other pole of the human mind, as Simon Leys said in a famous essay. With more than three millennia of written records, it has a vast history small libraries have been written about each of my individual chapters! And that history is growing by the day, with a constant flow of new discoveries in the past few years. Among a host of recent major textual finds still being evaluated and published, for example, are extraordinary collections of private letters, law codes and legal cases going back to the Qin and Han dynasties. Since the discovery of the Terracotta Army at the tomb of the First Emperor in 1974, there have also been many sensational archaeological finds, such as the remarkable prehistoric astronomical platform at Taosi, and though many are still unpublished, I have tried to give up-to-date accounts where possible a preliminary interpretation of the exciting finds at Shimao in the first chapter, for example, was only published by the excavators in 2017. Chinas early history in particular is a fascinating and constantly evolving field.

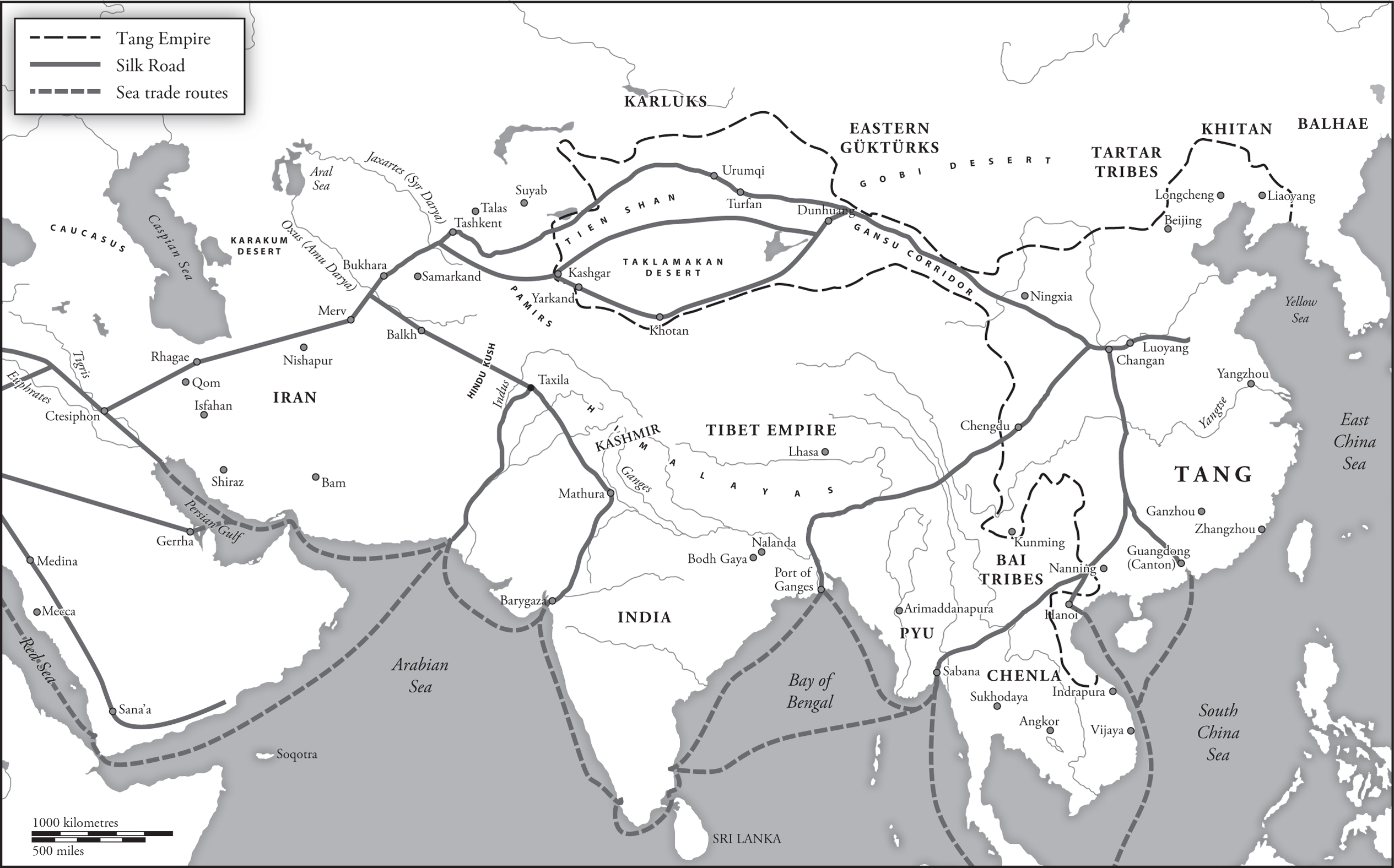

As regards the form of this book, in the manner of a film maker I have tried to keep the grand sweep narrative moving along while making detours to provide close-ups, homing in on particular places, moments and individual lives, voices high and low. For ordinary lives early in the story I have gratefully used the new finds, for example letters by soldiers in the Qin military the real-life Terracotta Army or letters from Han garrisons on lonely watchtowers in the wilds of the Silk Road, which give us the kind of immediacy we get in Britain from the Vindolanda tablets on Hadrians Wall. In the Tang dynasty there are letters exchanged between Buddhist monks in China and India. Later we have the correspondence of a mother and daughter caught up in the horrors of the Manchu Conquest; the diary of a child during the Taiping War; memos by loyal Confucian village officials in the declining days of the Last Empire; diaries and letters recounting tales of the Boxer Rebellion, the Japanese invasion and the Cultural Revolution. In all these cases, as the reader will see, I have used as a regular device the view from the village in the belief that the big story can be fruitfully illuminated from the grassroots.

I have often been led, inevitably, by personal interests; hence my sometimes extended sections on individual people, for example on the Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang, whose journey to India initiated one of historys great cultural exchanges; the poets Du Fu and Li Qingzhao, who lived through the cataclysms that engulfed the Tang and the Song; the free and easy wanderer Xu Xiake, who saw the decline of the Ming; Chinas most loved novelist, the tragic Cao Xueqin, who lived during the splendours of the eighteenth century; the electrifying feminist revolutionaries Qiu Jin and He Zhen at the end of the empire. Brought to us by superb translators, such as Patricia Ebrey, Ronald Egan, Julian Ward, David Hawkes, Dorothy Ko and many others, their brilliant and powerful words enable us to weave their dramatic life stories into the tale of their times.

Rebecca

Rebecca