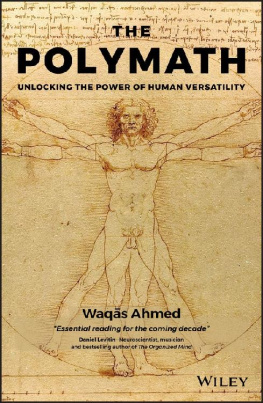

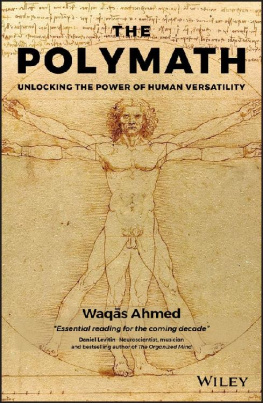

THE POLYMATH

Unlocking the Power of Human Versatility

WAQS AHMED

WILEY

This edition first published 2018

2018 Waqs Ahmed

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data is Available:

ISBN 9781119508489 (hardback)

ISBN 9781119508519 (ePub)

ISBN 9781119508526 (ePDF)

Cover design: Wiley

Cover Image: FineArt/Alamy Stock Photo

Contents

Prologue

Marking 500 Years Since the Death of Leonardo Da Vinci, the Archetypical Polymath

Leonardo, the uomo universale (universal man), is most peoples idea of a polymath.

Painting, sculpture, architecture, stage design, music, military and civil engineering, mathematics, statics, dynamics, optics, anatomy, geology, botany and zoology Leonardo pursued most of these at a level that warrants mention in any history of these subjects. Professionals in many of these fields see Leonardo in themselves, claiming him for their ideal.

It is entirely appropriate that the cover of Waqs Ahmeds The Polymath should be Leonardos Vitruvian Man, the outstretched figure inscribed in a square and circle, based on The Ten Books on Architecture by Vitruvius. It is Leonardos visual hymn to the essential oneness of human beings, the world and the cosmos. It is often used opportunistically in advertising and elsewhere to endow something routine with apparent profundity. Here, however, it is central to Ahmeds endeavour.

Given how we now classify and compartmentalise intellectual and practical pursuits, we tend to see Leonardos diversity. He saw unity. The unity was that of the fundamental organisation of the physical world, which fell under the embrace of the principles of mathematics, that is to say number and measure termed arithmetic and geometry, which deal with discontinuous and continuous qualities with the utmost truth. Behind the myriad diversity of forms in nature lay a set of coherent and consistent laws about how form fitted function in the context of natural law. These universal laws could be extrapolated from behaviours of light, the motion of solids and fluids, the mechanics of the human body and from every phenomenon that involved action, either as a process or as a result. As an example, he saw the vortex motion of water as expressive of the same rules as the curling of hair. We now assign the former to dynamics, the latter to statics. He saw across boundaries that we now use to separate branches of knowledge. My personal discovery of Leonardos unity is recounted in my recent Living with Leonardo, which tells of a personal journey that began with a degree in science and culminated in the worlds most expensive work of art, the Saviour of the Cosmos.

Leonardos mathematical polymathy was of a particular kind, but I do think it likely that most polymaths see more unity in their diversity than we can readily discern. They are better at seeing relationships, analogies, commonalities, affinities, relevancies, underlying causalities, structural unities. It is of course difficult in our modern world for an artist to work as a professional engineer something that was accepted in the Renaissance, even if uncommon. Any polymath today cannot but be aware of the jealously guarded professional boundaries that need be crossed. Institutional structures, erected most diligently in the nineteenth century, leave no doubt where these boundaries are. They are designed to keep outsiders out and insiders in. Massive bodies of professional knowledge certify the status the specialists, supported by forests of jargon and barricades of acronyms. The high demands of modern disciplines are real but they are also serve as protective ramparts against everyone who does not belong.

Polymathy in modern societies runs the risk of shallowness and amateurism. We are aware of the stigma that a polymath is a jack of all trades and a master of none. But there is an older expanded version, A jack of all trades is a master of none, but often better than a master of one. So many of the great innovations in the arts and sciences arose when outside wisdom was brought to bear on a discipline that had become complacent in its own criteria. Biology in the era of DNA was reformed by the arrival of physicists and chemists. Copernicuss sixteenth-century revolution was driven as much by concepts of beauty as innovatory observation. In 1905 Einstein wrote with eloquent brevity about a vision of space, time and energy, founded upon radical intuition, rather than undertaking a comprehensive review of what was right and wrong in modern astronomy and physics as then constituted. He was an insider who managed to stand outside.

There is of course a danger in conquering someone elses territory without due respect and humility. I see this with Leonardo studies. Modern professionals in, say, engineering, assume they can solve the problem of understanding Leonardo through their privileged and narrowly focussed knowledge, transposing Leonardo into the modern world as a man ahead of his time. The result is distortion. Something similar occurred when the artist David Hockney claimed that painters have long used optical devices to assist their depiction of nature an idea with which I have much sympathy. This opened the door to experts in modern optics, not least in lenses, who had scant interest in the nature of early optical instruments and what the business of picture-making was like at the time. In characterising the past, we need to be alert to the arrogance of the present.

True polymathy involves a unique and improbable blend of incorrigible ambition, undeterability, imagination, openness, and humility. It cannot be the same as it was in Leonardos day. However the principle of seeing something as if it were something else seeing it as belonging in other than its normal conceptual place is more vital now than ever if we are to nurture the cultures of mutual understanding that are necessary for the survival of the human race.

Martin Kemp

Emeritus Professor of the History of Art, Oxford University

Preface

A mind that is stretched by new experiences can never go back to its old dimensions.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

My interest is in the pursuit of the optimal life. That is, in developing a mind and experiencing a life that is the richest it can be. So while this book proposes a new way of thinking, it also sets out a new way of being human, a new way of living different from that which has been set out for you as normal by forces that claim to know better. It calls for an extraction of the soul from the current paradigm, like an astral projection, and a visit to the realms of history and possibility. It must all begin by living the conscious, mindful life, by switching the mind on to think more often and more effectively about the objects and their connections, the whole and the particular, the philosophical and the practical so that you can become all you can be: the complete you.

I was not commissioned to write this. It was purely a personal intellectual odyssey until recently when I realised it became too important a thing not to share with the world. As such, work on it was woven between a range of experiences physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual and otherwise each giving me a unique insight into the topic at hand.

After all, you are what you experience. Each and every thought, emotion and inflow of knowledge will either subtly or fundamentally impact your perspective on any given thing over time. This is not just intuitive speculation, but a neuroscientific fact. Your evolving nature manifests in your connectome the complex, ever-changing circuitry unique to each brain. As such, I was both proactive and reactive in researching and writing this book. I didnt immerse myself in the subject, except for intermittent periods. Complete immersion would have risked the sort of narrow-minded specialisation that this book ultimately seeks to challenge. Conscious of this, I allowed the knowledge from all other facets of my life over a five-year period to fuse, clash and connect with pre-existing material in my mind. Hence I remained open as to my approach, structure, content and conclusion, until the very end.

Next page