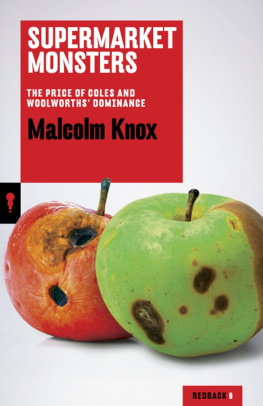

Except for a short stint in a superstore as a student many years ago, my experience of supermarkets had been the same as most peoples; Id rush in to complete the dull but essential chore that is the weekly shop, Id have no time for checkout girls and their small talk. Id rebuff offers of help tactlessly, make demands as though they were machines programmed to serve me without complaint, and promptly forget their names and faces seconds after rushing out. Little did I know that, behind the identity badges, unflattering uniforms and quiet smiles were individuals taking note of my every quirk, comment and foible.

Never again will I shop the same way. And neither will you.

When I began my six-month career as a checkout girl, the country was reeling from the possibility that we were headed for a full-blown recession. President Obamas election brought new optimism around the world but could not disguise the doom and gloom that lay ahead. The credit crunch and financial instability were one thing, but in the early autumn of 2008 things were about to get rocky for every man, woman and child in this countryas we slid into the worst recession the world has seen for decades.

Until that point the main casualties of the financial crisis were the banking institutionsNorthern Rock, Lehman Brothers, Citigroup, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, along with mortgage lenders and insurance companies. Most ordinary people were still watching developments from a safe distance. However, unemployment figures were creeping up, redundancies and job losses were looming and food prices were on the rise.

As a mother running a busy home and working in a volatile industry I had started to count my own pennies. My grocery shopping was now leaving my wallet disconcertingly light. Id push my trolley to the car park while staring at the receipt, aghast that the food in my bags now cost well in excess of a hundred pounds: I knew I had to make cutbacks. It was after one such shopping trip, clutching my hefty bill, that I turned back to look at the checkouts and it dawned on methis was the front line of the recession, where the reality of the downturn really hit home. And thats how I embarked on my quest to see what a billion-pound hole in our economy would really mean for us all.

Someone, with not much time for reporters, once told me that Journalists always report from the outside in and so only ever see the story from a superficial vantage point. My episodes of immersive, experiential or undercover journalism have allowed me the privilege of reporting from the inside out. This requires a degree of individual sacrifice, intrusion, duplicity and commitment that usually leaves me slightly unhinged. However awkward it is personally, thankfully it serves the purpose of shedding light on the truth in a way that turning up with my notebook, pen and press pass never could do. This is that truth.

Why did I choose Sainsburys? Actually it chose me. Last autumn, jobs in retail were hard to come by and I searched and applied for a number of positions in various supermarkets before this vacancy cropped up. I had to complete an in-depth online assessment and attend an interview: I got the job. In my first month, as the crisis deepened, I was convinced that, like many other retailers, the supermarkets would eventually fall victim to the downturn. I couldnt have been more wrong. I sat at my checkout, week in week out, for six months observing first-hand how the nation was adapting to the onset of what would soon be described as the worst global recession since the 1930s. At first, customers were spending hard and most appeared unruffled by the storm brewing ahead. And then as the year drew to an end, I saw a shift: money-saving tactics kicked in, savvy food choices were being made, offers were hunted down and customers were watching the pennies carefullythe recession was starting to bite. I witnessed for myself how the average British family was suffering, as people opened up to me about their money troubles. And some didnt stop there; I listened, mouth agape, as customers launched into full-blown confessions about their personal lives, divulging their most private thoughts.

To us they are just cogs in the supersonic wheel of our supermarkets, but Checkout Girls and Guysor Cogs, as I secretly referred to themhave incredible stories to tell and intriguing interwoven lives of their own. Behind the tills, in the shopping aisles, across the customer service desk, beyond the doors leading to the back of the store and upstairs in the canteen and locker rooms, family dramas are played out, love affairs and friendships flourish and sometimes wilt. Here, several members of one family work together, along with friends who grew up together, neighbours, former school friends and flat-mates. At times its like a small, cosmopolitan village, at others like a big, bustling, multi-racial family. And on a daily basis they welcome us as shoppers right into the heart of their community while unwittingly becoming spectators to our personal and financial dramas. Against all my expectations I walked straight on to the set of a gripping soap opera in which all of us have a walk on part. The Cogs I met were in Sainsburys, but they are in every supermarket and in every townand they are watching you. This is their story.

The Checkout Girl

So here I am. Day One. My hairs tied back, my shoes are low-heeled and sensible but even though Ive got my orange name-badge on, Im still me. That may be because I havent been given my bright blue polyester polo shirt and high-waisted, wide-bottomed, narrow-legged, creased-down-the-front trousers yet.

At Sainsburys, becoming a checkout girl or Cog requires a two-day training course. Staff recruitment is serious business here, and as I wait in the canteen Im given a quick summary of what well learn today: the supermarkets raison dtre, history, financial status, aims and objectives, health and safety rules and, most significantly, its guiding mottos:

Do you want your bonus? Then, always smile, take the customer to the product and offer an alternative. Above all, be friendly.

The mantras are many in number and imprinted on beige-cream A4 pages, crumpling a little at the corners, stuck all the way up the stairwell. And right next to the clocking-in and (equally importantly for all supermarket workers) the clocking-out machine is a poster signed by shop-floor staff all promising to smile more, be more helpful, and treat the customer like someone special. These are the Cogs countless messages pledging allegiance and promising to be better at their jobs. It reads like a giant farewell card written by signees at gun point.

Our trainer finds it impossible to refrain from bragging about how well this store is doing.

The credit crunch has not affected us, we are told. We are set to take a million by the end of this week, she crows, smiling smugly. Weve already taken 16,000 on clothes today. Her grin is now wider than a Cheshire cat.

We have to sign the contract on the spot and hand it back immediately. When I ask if I can get a copy, I am brashly told, Youll get one once Personnel have signed it, with no indication given of when that might be.

Sickness policy: There is no sick pay for six months and if you are ill you only get statutory sick pay.

Holidays: You need to book that now.

Overtime: Whether you like it or not, youre going to have to put in extra hours and swap shifts. Its a matter of You scratch my back, and Ill scratch yours.

Breaks: One hour unpaid lunch for checkout staff if you do a full day. But depending on the number of hours worked this could be a fifteen-, twenty-, thirty- or forty-five-minute paid break. On top of lunch? Instead of lunch? Im not clear and she doesnt provide clarification either.