Veronica Della Dora - Mountain

Here you can read online Veronica Della Dora - Mountain full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Reaktion Books, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Mountain

- Author:

- Publisher:Reaktion Books

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mountain: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mountain" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mountain — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mountain" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

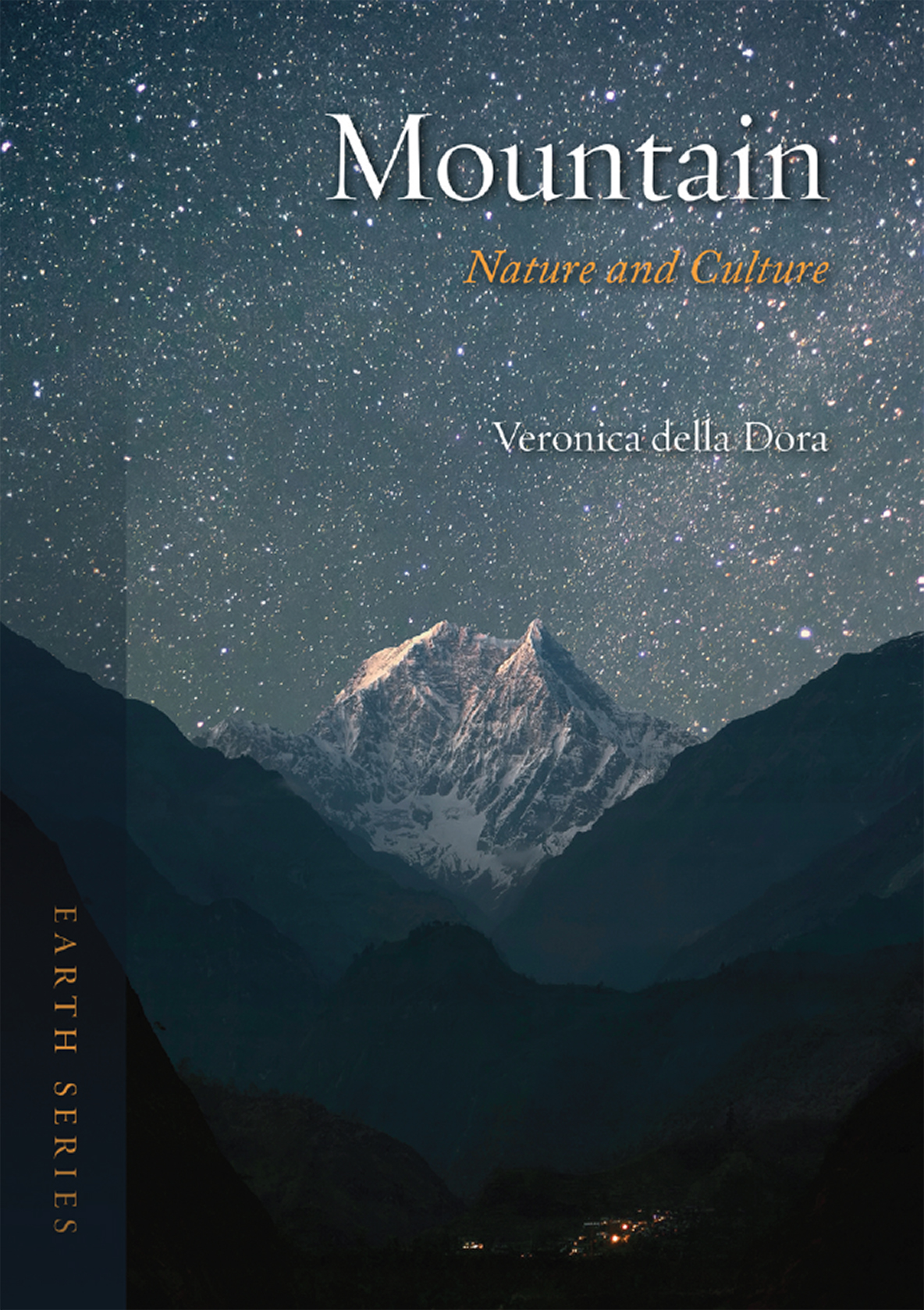

MOUNTAIN

The Earth series traces the historical significance and cultural history of natural phenomena. Written by experts who are passionate about their subject, titles in the series bring together science, art, literature, mythology, religion and popular culture, exploring and explaining the planet we inhabit in new and exciting ways.

Series editor: Daniel Allen

In the same series

Air Peter Adey

Cave Ralph Crane and Lisa Fletcher

Desert Roslynn D. Haynes

Earthquake Andrew Robinson

Fire Stephen J. Pyne

Flood John Withington

Gold Rebecca Zorach and Michael W. Phillips Jr

Islands Stephen A. Royle

Lightning Derek M. Elsom

Meteorite Maria Golia

Mountain Veronica della Dora

Moon Edgar Williams

South Pole Elizabeth Leane

Storm John Withington

Tsunami Richard Hamblyn

Volcano James Hamilton

Water Veronica Strang

Waterfall Brian J. Hudson

Veronica della Dora

REAKTION BOOKS

Alla mia mamma che ama le montagne

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448, Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2016

Copyright Veronica della Dora 2016

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780236957

Aiguille du Midi.

Among all geographical features, mountains are commonly deemed to be the most permanent. Majestic and awe-inspiring, mountains are the first objects in a landscape to capture our attention. Their hard stone transcends human temporariness; it is an absolute mode of being. As such, mighty rocks and peaks are key protagonists of ancient cosmogonies and of most religious narratives. In the West, mountains are also places that have helped to shape our perceptions of wilderness and of the sacred. Their cultural history is largely the history of our relationship with the natural and supernatural Other.

The wilderness and the sacred share two main similarities. First, they both evoke separation from the ordinary against which they are defined. Second, taken literally, they both cause bewilderment, wonder, displacement. Wilderness is psychological as much as it is geographical: it can be a state of mind and a state of the land. Yet for many today the term wilderness evokes nostalgia, compassion, perhaps even a sense of moral guilt, rather than threat or mystery. In the Western geographical imagination, wilderness, like the sacred, is no longer boundless terra incognita, but, rather, a fragile archipelago to be safeguarded from the evils of modernity.

Wilderness and the sacred converge on mountain peaks, as do shifting attitudes to these two concepts. Historically mountains have repulsed and attracted. They have been appreciated and despised as sites of divine and diabolic sublimity, as abodes of gods and demons, of hermits and revolutionaries. Progressively domesticated, today they nevertheless continue to attract seekers of spiritual quietness and extreme emotions alike, as well as weekend excursionists seeking a break from the everyday. The reason is that mountains, like the sacred, are usually perceived as wholly other. Floating above the clouds, materializing out of the mist, mountains appear to belong to a world utterly different from the one we know. They demand separation from the ordinary, removal from earthly concerns even for a brief moment.

Sunset on the Dolomites.

The history of mountains is deeply interlaced with our cultural values, with our aesthetic tastes and scientific practices. Over the centuries mountaintops have been repeatedly lowered and elevated by the human imagination. New summits have been occasionally carved out of the land through scientific convention; others have been spoiled by intensive mining. Mountains, one might argue, are geological forms as much as they are social constructs. Yet there is something elemental about mountains that exceeds and transcends our attempts to ascribe meaning to them. How have conceptions of wilderness and the sacred been shaped through mountains? What do mountains teach us about the relationship between wilderness and the sacred? And, ultimately, what do they teach us about our relationship with our planet and with the transcendent? This book addresses these questions.

Domenico di Michelino, La Divina commedia di Dante, 1465, fresco in the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence.

We have probably all been faced with a mountain of problems at least once in our lives. Some of us might often find ourselves buried under a mountain of work. And those with a bad temper might end up making a mountain out of a molehill. Mountains punctuate our everyday speech as they punctuate the earths surface. Whether physically or metaphorically, they strike us for their insistent materiality and for their prominence. In fact, the Latin term for mountain (mons) shares its root with the word prominence (as do eminence and imminent). Likewise, amount a word that entered the English lexicon in the thirteenth century comes from the Latin phrase ad montem (to the mountain).

Mountains cover 24 per cent of the earths surface and, while most of them pre-date human existence, their outlines have served as immutable backdrops to human history. Due to their prominence, some have provided different civilizations with distinctive landmarks or have been believed to be the seats of divinities (for example, Mount Olympus in ancient Greece, Mount Kailash in Tibet and the Navajos Mount Taylor). Others have been used as defensive barriers from the Barbarian incursions into the Roman Empire to the Nazi Blitzkrieg of the Second World War. Mountain ranges like the Alps and the Pyrenees helped define the limits of emerging nation states in early modern Europe, whereas in the eighteenth century the Urals set the arbitrary continental border between European and Asiatic Russia.

Destroy a country, but its mountains and rivers remain, a Japanese proverb says. If the mountain will not come to Muhammad, Muhammad must go to the mountain, we hear in different languages. The fact that mountains can hardly be moved is acknowledged in various cultures and is used to express persistence of circumstances (and thus the necessity to adapt to them), of human habits and of belief. After all, we learn from the New Testament that only faith can move mountains (Matthew 17:20 and 21:21).

Yet if mountains seem to be the most solid and stable of all geographical objects, semantically, they are probably also the most unstable. It is very easy to point at a mountain, but it is very difficult to establish exactly what a mountain is. If you ask someone to draw a mountain, they will normally produce a well-defined triangular shape, but this is not what we find in nature most of the time. It is curious, John Ruskin observed, how rarely, even among the grandest ranges, an instance can be found of a mountain ascertainably peaked in the true sense of the word pointed at the top, and sloping steeply on all sides. These archetypal mountains are usually those that attracted ancient myths and sacred narratives, as well as modern climbers. However, they are exceptions, rather than the rule.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Mountain»

Look at similar books to Mountain. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mountain and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.