Adriano Prosperi - Crime and Forgiveness

Here you can read online Adriano Prosperi - Crime and Forgiveness full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Crime and Forgiveness

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crime and Forgiveness: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Crime and Forgiveness" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Crime and Forgiveness — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Crime and Forgiveness" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CRIME AND FORGIVENESS

Christianizing Execution in Medieval Europe

ADRIANO PROSPERI

Translated by Jeremy Carden

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

2020

Copyright 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

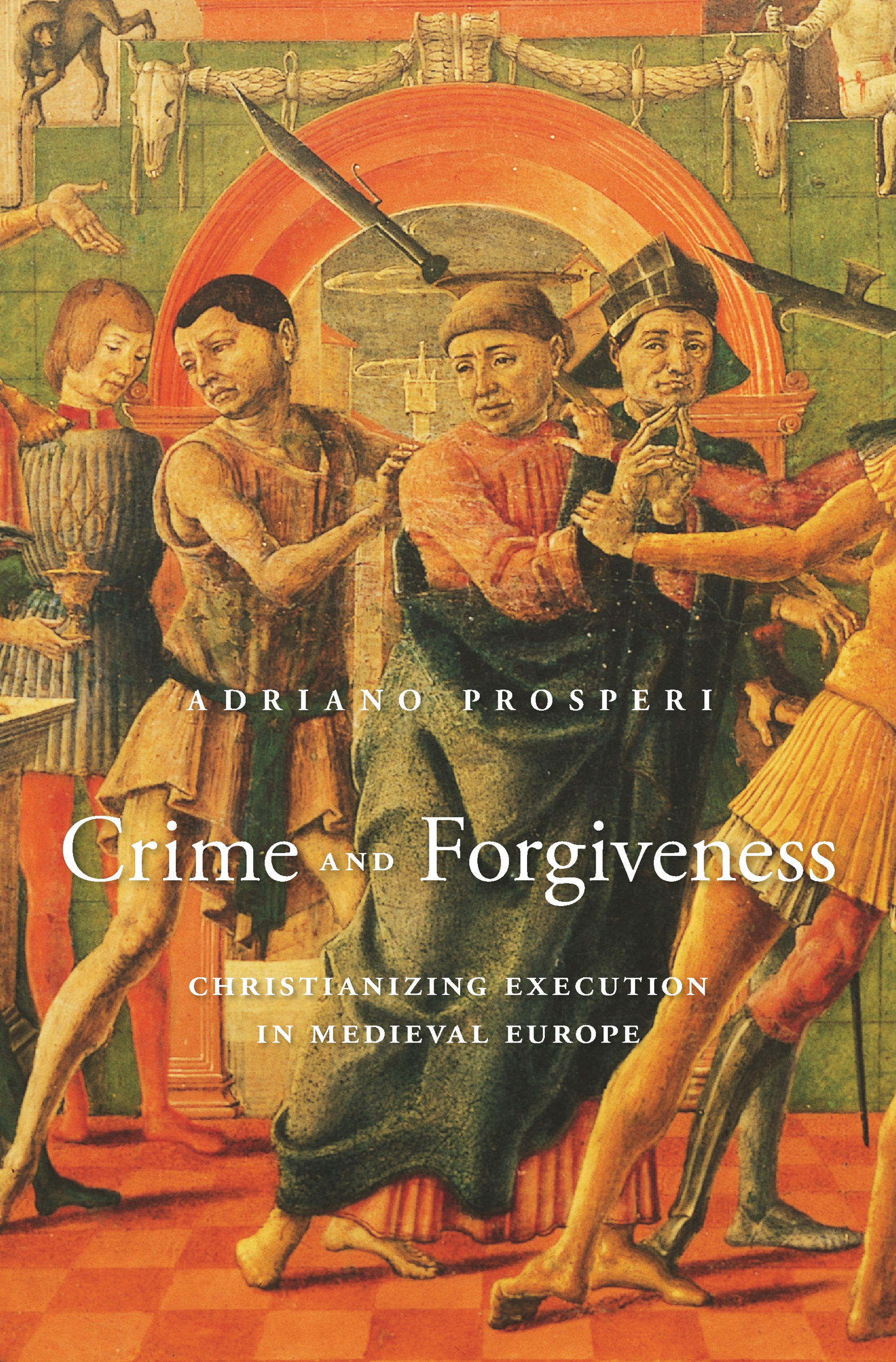

Jacket design - Lisa Roberts

Jacket art - Altarpiece of St Maurelio, scene condemnation of St Mauritius, ca 1480, by Cosm Tura (1430-ca 1495), oil on wood, diameter 48 cm / De Agostini Picture Library / A. De Gregorio / Bridgeman Images

978-0-674-65984-1 (hardcover)

978-0-674-24027-8 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24028-5 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24026-1 (PDF)

Originally published in Italian as Delitto e perdono: La pena di morte nellorizzonte mentale dellEuropa cristiana, XIVXVIII secolo, Nuova edizione riveduta, Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi Storia. Copyright 2013 and 2016 by Giulio Einaudi editore, s. p.a., Torino.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Prosperi, Adriano, author. | Carden, Jeremy, translator.

Title: Crime and forgiveness : Christianizing execution in medieval Europe / Adriano Prosperi ; translated by Jeremy Carden.

Other titles: Delitto e perdono. English

Description: First. | Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2020. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019044040

Subjects: LCSH: Capital punishmentEuropeHistory. | Capital PunishmentReligious aspectsCatholic ChurchHistory. | Capital PunishmentReligious aspectsChristianityHistory.

Classification: LCC HV8699.E85 P7613 2019 | DDC 364.66094/0902dc23

LC record available at https:// lccn .loc .gov /2019044040

This book recounts the way in which a religion born from the preaching of Jesus of Nazareth, a Jew who was condemned to death and crucified, legitimized the death penalty for over a millennium. But actually it did much more than that: it transformed capital punishment into a great public ritual and made the condemned person a figure of Christ, that is, someone willing to accept death in order to save humanity. The person who had been condemned to death for their crimes was expected to offer an example of a Christian death, declaring remorse for what they had done. In some penal systems, like the English one, the condemned had to give a last speech to the crowd, describing their misdeeds and exhorting the audience not to follow their example.

After the display of remorse and the plea for forgiveness, members of religious associations or Protestant pastors handed over the prisoner to the executioner and his assistants, who sometimes simply proceeded with the hanging or beheading, but very often had the task of making the prisoner suffer through mutilation, hot irons, and other forms of atrocious suffering that might last for a whole day. Among them was the breaking wheel, envisaged, like all the other terrible forms of punitive torture, by Charles Vs penal Constitution of 1532. All of this took place in the presence of the crowd and with the blessing of one or more churchmen: Catholic chaplains, Protestant pastors, members of associations specialized in comforting the condemned. They were the ones who, in the preceding days, had prepared the prisoner to meet their death, persuading them that if they expressed remorse and asked for forgiveness, their soul would live forever in the bliss of heaven.

This religious legitimation of violence on the scaffold was for a long time one of the contradictions of human history: not the only one, but certainly one of the biggest in Western Christian culture and one of the most widespread in the world. This book, though long, offers just a rough idea of the many forms taken by this fundamental model. I have been able to do no more than give a brief account of a vast body of documentation relating to a large number of intellectual constructs and institutions extending all over the Christian West. Testimony to these practices and events can be found in architectural monuments, in artistic and literary creations, in poetic, musical, and theatrical compositions. If the Italian tradition occupies a bigger place in my account, it is because the Misericordieassociations of men and women set up to comfort the condemned and bury their bodieswere founded in Italian cities. Starting in the fifteenth century, the model branched out from there throughout the Christian world and beyond. The discovery of America, contacts with the East and with Islam, and the shattering of the unity of the Western Church in the age of the Reformation multiplied its proliferation, which was split and reflected as in the fragments of a mirror. The Anglo-Saxon readers to whom this translation is addressed will recognize in it certain aspects of their own legal and religious traditions.

But this historical study also has the ambition of being more than just a straightforward description. From an anthropological point of view, I consider the scapegoat theory proposed by Sir James Frazer and later picked up on by Ren Girard to be valid: the condemned person is like the goat on which the Jewish priest laid his hands during Yom Kippur, transferring to it all the sins of the people before shooing it off into the desert. The community concentrated all the evil that afflicted it, and that had been expressed in the violence of the crime, on the condemned criminal. By eliminating the criminal, the community purified itself and eliminated the evil, but at the same time asked the prisoner to accept full responsibility and to forgive their executioners. But as the condemned person is a human being and not an animal, the contradiction between the Gospel message of forgiveness and fraternity and the supreme violence of legally taking someones life was resolved with the distinction between body and soul: the soul has a life of its own, survives the death of the body, and lives forever in another dimension. When, in eighteenth-century European cultures, there began to be a crisis of faith regarding the existence of the soul and the Christian afterlife, the religious foundations of capital punishment started to crumble as well, and the death penalty was first abolished by the grand duke of Tuscany, Peter Leopold, in 1786. This was preceded, in 1782, by the abolition of the ecclesiastical Inquisitionthe disarming of the religious court.

The division between the life of the body and the life of the soul is being reproposed today by the forms of warfare waged by fringe groups of so-called radical Islam. What makes the threat difficult to counter is the religious conviction of the terrorists, who believe that by becoming human bombs and blowing themselves up in order to kill as many people as possible, they will earn the prize of martyrsa place in paradise. The instinct for self-preservation that acts as a brake on the killers and terrorists of our cultures cannot be relied upon in their case. And yet similar phenomena can be found in European Christianitys past: those who killed Gods enemies (heretics, infidels, Jews, rebels) were guaranteed the reward of eternal beatitude.

So does radical Islam rest on ancient beliefs that are destined to fade away? Maybe. But one thing is certain: religion has an inerasable capacity to exert a grip on human minds and bring about great upheavals. The bond between religion and pain, and between injustice and death, is deep and hard to erase. It is part of what Kant called the crooked timber of humanity. There is no guarantee that our own past will not come back to life, even though it may take unexpected forms.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Crime and Forgiveness»

Look at similar books to Crime and Forgiveness. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Crime and Forgiveness and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.