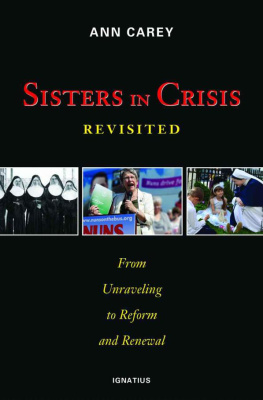

SISTERS IN CRISIS

Ann Carey

Sisters in Crisis, Revisited

From Unraveling to Reform and Renewal

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

First edition

Sisters in Crisis: The Tragic Unraveling of Womens Religious Communities

1997 by Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division

Our Sunday Visitor, Inc.

All rights reserved

Cover images (from left to right)

Sisters of St. Francis, including Mother Marianne Cope (far right), serving

at the Branch Hospital for Lepers in Hawaii, 1886

Sister Simone Campbell, executive director of Network, speaking in Ames, IA,

during a nine-state Nuns on the Bus tour, Monday, June 18, 2012

AP Photo / Charlie Neibergall

A Sister of Life visiting with two children outside the Basilica of St. John the Evangelist

in Stamford, CT, after a profession of vows ceremony, August 6, 2012

Photo by Amy Mortensen

Cover design by John Herreid

2013 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-789-8

Library of Congress Control Number 2012953858

Printed in the United States of America

To my teachers, the Sisters of Loretto and the Sisters

of Saint Joseph of Carondelet

CONTENTS

I. Post-Vatican II Sisters: Ready for

Renewal or Revolution?

PREFACE

The situation for women religious in the United States has changed considerably since the first edition of Sisters in Crisis was published in 1997. Some of the new as well as some of the established orders of sisters who live the classic, traditional style of religious life have been thriving and attracting vocations. An apostolic visitation of US sisters was approved by Pope Benedict XVI and was conducted between 2009 and 2011. An assessment of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR) carried out by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith from 2008 to 2012 found that the conference had serious doctrinal problems. Prominent sisters have taken public positions, contrary to those of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, in support of legislation that allows funding for abortion and denies the conscience rights of those who object to immoral medical procedures.

This new edition of Sisters in Crisis covers all of these important developments while retaining most of the original content in order to provide in one book a history of US sisters since the Second Vatican Council closed in 1965. The historical background in the first edition sheds considerable light on the events that have occurred since 1997, for many of the subsequent developments were foreshadowed by and built upon previous ones. This history reflects the forbearance of the Vatican, which had tried for more than forty years to reform religious life and the conference of women superiors before it initiated the apostolic visitation and doctrinal assessment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to acknowledge the valuable contribution of the many sisters who have shared their experiences, prayers, and suggestions for this work. These sisters belong to a variety of religious institutes, including those of the Benedictines, Carmelites, Daughters of Charity, Dominicans, Franciscans, Holy Cross, Immaculate Heart of Mary, Little Sisters of the Poor, Loretto, Mercy, Notre Dame, Saint Joseph, Sisters of Charity, Sisters of Christian Charity, and Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. Most of these sisters have asked not to be named, as they did not want to be perceived as criticizing their religious institutes to which they are unfailingly loyal. Some of them wanted to remain anonymous because they feared retribution from leaders who hold views different from their own. Some sisters who were not named in the first edition are named here, as they have passed on to their eternal reward and I wish to honor them by acknowledging their names.

I also am indebted to the staff of the University of Notre Dame archives, who graciously and patiently helped me access material in their holdings. Among the collections at Notre Dame were the records of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), the National Assembly of Religious Women (NARW), and the Consortium Perfectae Caritatis. Much of the material gathered from primary sources in those collections, such as correspondence and meeting minutes, was published for the first time in the first edition of this book.

INTRODUCTION

For more than 150 years, religious sisters have been the backbone of the Catholic Church in the United States. Sisters built the parochial school system as well as the Catholic health care and social-service systems. Sisters helped dioceses and parishes spread the Catholic faith to the unchurched while ministering to the spiritual needs of the Catholic people. Perhaps most important, sisters dedicated their lives to giving visible witness to the transcendence of God and to the spiritual aspect of our humanity.

The US Church had 180,000 sisters in 1965, but by 2012, that number had dropped to 55,000, with the median age in most orders being over seventy. Sisters have nearly disappeared from many Catholic institutions, and some of the sisters who are still visible seem to be very angry with the Church in general and with the male hierarchy in particular. Within many orders, the sisters themselves seem to be divided about how religious life should be lived: Some wear religious garb and continue to work in Catholic institutions while others in the same community wear regular clothes, live alone in apartments, and work in secular occupations.

Journalists are trained to ask questions referred to as the five Ws and the H. During the thirty-plus years that I have worked as a journalist in the Catholic press, I have often pondered these questions: Who led the changes in religious life, and who were most affected by them? What events and ideas influenced these changes? When did the philosophy of religious life change? Where have all the sisters gone? Why was the renewal of religious life interpreted so differently by so many sisters? And how did religious life for sisters evolve into its current state of crisis? For this new edition of Sisters in Crisis , I would add one more question to those original ones: Why are the orders that have embraced the classical model of religious life attracting the most vocations? My research and experience have helped me find the answers to these questions, which I detail in the following pages.

In order to simplify a complex topic, I have used consistent terms throughout the book. Strictly speaking, there are some canonical differences between the terms institute, community, congregation and order . In general usage, however, these terms are used interchangeably, as they are in this book. Similarly, the term nun refers canonically to a woman who belongs to a cloistered or contemplative order and remains behind convent or monastery walls, while sister is the canonical term for women religious who belong to congregations that are engaged in apostolic work. Most laypeople are not aware of this distinction, so these terms also will be used interchangeably in this book, although the topics covered refer only to sisters who are members of apostolic communities and do not apply to the approximately four thousand nuns who belong to contemplative institutes.

An additional matter of clarity involves the four-hundred-plus religious institutes of women in the United States. Some of these institutes are provinces of international orders that have headquarters in other countries. For example, the motherhouse of the Sisters of Saint Francis of Perpetual Adoration is in Olpe, Germany. There are two American provinces: the Eastern, or Immaculate Heart of Mary, Province in Mishawaka, Indiana; and the Western, or Saint Joseph, Province in Colorado Springs, Colorado. On the other hand, some US religious institutes, such as the Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne, were started in this country. The larger institutes of women religious, whether they are international or domestic, usually are divided into several provinces in this country. The province of a particular order, however, should not be confused with an autonomous order. Many of these diverse institutes of women religious were founded on the same tradition or rule, and the names of their institutes are very similar. Hence, many laypeople think that institutes founded under the same rule are somehow connected. This is not the case except for provinces of the same institute.

Next page