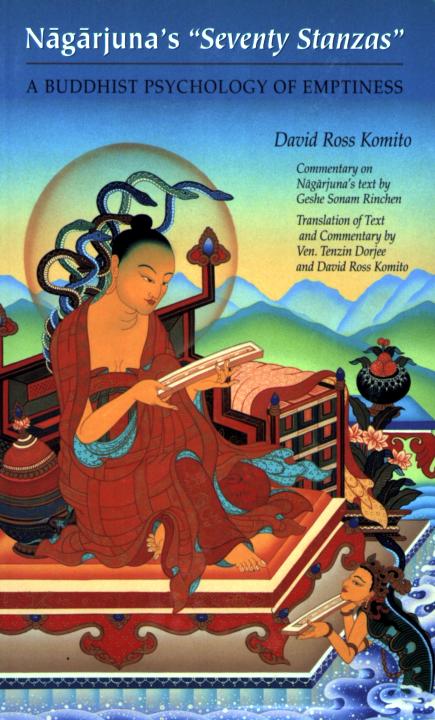

David Ross Komito - Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness

Here you can read online David Ross Komito - Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

David Ross Komito

Translation and commentary on the Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness by Venerable Geshe Sonam Rinchen, Venerable Tenzin Dorjee, and David Ross Komito.

The author wishes to express his gratitude to his many teachers, without whose kind instruction this work could never have been accomplished, and especially to Helmut Hoffmann, Tara Tulku Kensur Rinpoche, and Geshe Sonam Rinchen. The author also wishes to thank the National Endowment for the Humanities, whose grant of a Summer Stipend was instrumental in the completion of this project.

Chapter 1 19

Section

Chapter 2 77

Section

Chapter 3 183

Section

"Reality according to Buddhists is kinetic, not static, but logic, on the other hand, imagines a reality stabilized in concepts and names. The ultimate aim of Buddhist logic is to explain the relation between a moving reality and the static constructions of thought."

T. Stcherbatsky

Buddhist Logic

Vol. 2, p. 2

In the summer of 1982 I traveled to Dharamsala, India to do some advanced study on Nagarjuna's Madhyamika system with Geshe Sonam Rinchen, one of the scholars at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. I had reached a limit in what I could understand about Madhyamika by merely reading texts, and had a number of questions which remained unanswered. I felt that these questions could only be answered through dialogue with an accomplished scholar who had trained in the venerable monastic tradition.

For some time the focus of my Madhyamika studies had been Nagarjuna's treatise Shunyatasaptatikarikanama, the Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness (hereafter referred to as the Seventy Stanzas). I'd begun work on this treatise while a graduate student, translating it under the supervision of Professor Helmut H. Hoffmann and commenting upon it and its relation to the Prajnaparamita literature for my Ph.D. dissertation at Indiana University. In this project we utilized the standard commentaries on the Seventy Stanzas for guidance. The translation produced at that time replicated the terseness of Nagarjuna's treatise. In the course of our work together I had learned much about Nagarjuna's system, but felt that what I didn't know was perhaps even more vast as a result of having learned a title. Frustratingly, there seemed to be few, if any, scholars in the west with whom I could consult who were any better off.

As I began asking Geshe Sonam Rinchen my questions about the Seventy Stanzas, I realized that I had finally met a true treasure house of knowledge about Madhyamika. He had begun his studies at Sera Monastery in Lhasa, Tibet, fled in 1959 to India with about 100,000 other Tibetans and completed his scholarly studies there, finally obtaining his Geshe (Doctor of Theology) degree. His answers to my questions were always lucid, and many difficult points in Madhyamika began to come clear. Amazingly, when I put questions to him he often asked me which explanation did I want? As he showed me, there were many ways to analyze the subtle points in Nagarjuna's system. His own preference was to adopt the Prasangika view of Candrakirti, as his monastic tradition followed the Prasarigika interpretation favored by Tsong kha pa, the founder of the dGe lugs pa sect to which Sera was connected. I found that this view profoundly enriched my understanding of the Seventy Stanzas, a draft of which I had brought with me.

In the course of our discussions we determined that the most profitable way for me to continue my training in Madhyamika would be for us to read the Seventy Stanzas from beginning to end, discussing problems as they arose in our reading. As our reading progressed I began to revise my translation of the Seventy Stanzas under Geshe Sonam Rinchen's direction, all the while taking notes on his explanations of the significance of the stanzas (Sanskrit: karika(s)). During this process I realized that my notes represented a nucleus of a contemporary commentary on this ancient treatise which reflected both the views of Candrakirti and the oral tradition of interpretation which Geshe Sonam Rinchen had learned in Sera.

This struck me as being of particular value, and after some discussion we determined to continue our work with the formal intention of actually producing a contemporary commentary on the Seventy Stanzas which could be of use to the modem reader. This is also why we did not choose simply to translate the Candrakirti commentary, for Candrakirti himself can be extremely difficult for the nonscholar, and we felt that we would have simply found ourselves in the regress of needing to comment upon Candrakirti as well as Nagarjuna, leaving the modern reader with a larger task, and perhaps not succeeding in providing him/her with what we had intended to provide: a readable version of one of Nagarjuna's philosophical treatises.

This desire to serve both the needs of the nonscholar and the scholar also presented us with a problem in translating. The terseness of the stanzas themselves is often very confusing to the nonscholarly reader, and both Geshe Sonam Rinchen and I felt that many other translations of Nagarjuna's treatises were prone to being inaccurately read, though translated correctly, simply because they were so terse. Therefore we determined to interpolate English words into our translation of the stanzas which are not found in the original text but do reflect the meaning of Nagarjuna, at least as the Tibetans interpret Nagarjuna. To preserve the accuracy of the translation we have adopted the device of italicizing all the words in the English translation found in chapter two, section 2-2, which actually correspond to the Tibetan. In section 2-1 the stanzas are presented without italics or commentary. In this way we hope to satisfy both the needs of the scholar for a precise translation and the needs of the nonscholar for a readable and comprehensible translation.

We have taken great care in our work to select English terminology which conforms to the style now being developed at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives and also which carries the appropriate English connotations. For this I must express special appreciation to Venerable Tenzin Dorjee, the third member of this translating project. Ven. Dorjee is fluent in both Tibetan and English, and has taken pains to develop his command of English by studying English Literature at Indian universities. We spent considerable time discussing the specific English words we wished to use in the translation of both Nagarjuna's treatise and Geshe Sonam Rinchen's commentary on it, attempting to select English words which had both the appropriate denotations and connotations. This was particularly difficult and yet important. In this respect our translation has the merit of being an accurate reflection of what an indigenous tradition believes the text is saying, and is not merely what western scholarship says the words in the text mean. Those who would prefer a more literal translation may wish to consult either my earlier translation of the Seventy Stanzas or else Chr. Lindtner's translation of it. I believe, however, that they will find our translation to be of great help in understanding Nagarjuna's thought.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness»

Look at similar books to Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nagarjunas Seventy Stanzas: A Buddhist Psychology Of Emptiness and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.