Sign up to receive weekly Tibetan Dharma teachings and special offers from Shambhala Publications.  Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

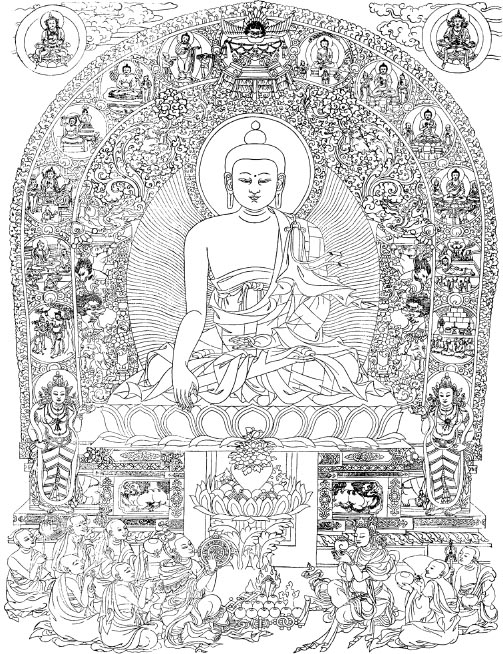

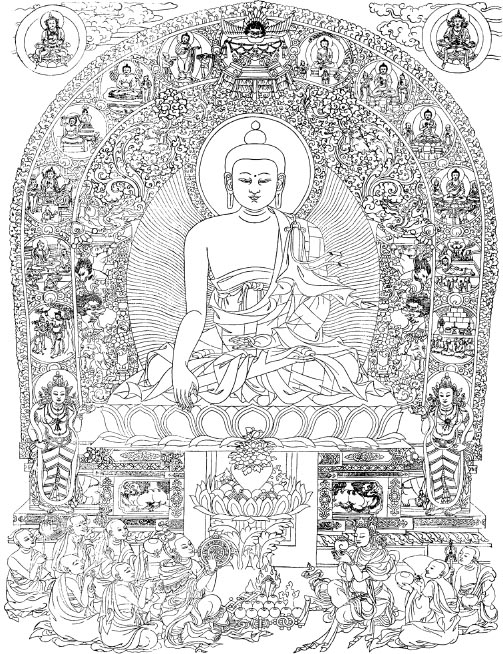

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.  Buddha Shakyamuni

Buddha Shakyamuni  Bodhisattva Manjushri

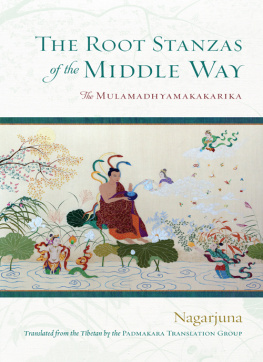

Bodhisattva Manjushri  Nagarjuna T HE R OOT S TANZAS OF T HE M IDDLE W AY The Mulamadhyamakakarika Nagarjuna TRANSLATED FROM THE TIBETAN BY THE Padmakara Translation Group

Nagarjuna T HE R OOT S TANZAS OF T HE M IDDLE W AY The Mulamadhyamakakarika Nagarjuna TRANSLATED FROM THE TIBETAN BY THE Padmakara Translation Group

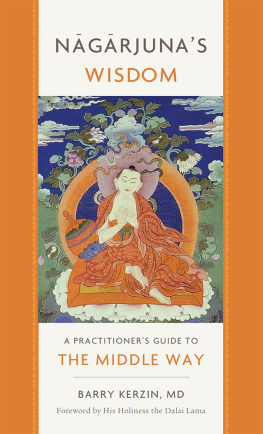

Shambhala Publications, Inc. 4720 Walnut Street Boulder, Colorado 80301 www.shambhala.com 2008 by Editions Padmakara Previously published privately in a limited edition in France by Editions Padmakara (2008). Cover design: Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Cover art: Cover painting of Nagarjuna by Livia Liverani used courtesy of Tsadra Foundation.

Shambhala Publications, Inc. 4720 Walnut Street Boulder, Colorado 80301 www.shambhala.com 2008 by Editions Padmakara Previously published privately in a limited edition in France by Editions Padmakara (2008). Cover design: Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Cover art: Cover painting of Nagarjuna by Livia Liverani used courtesy of Tsadra Foundation.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Names: Ngrjuna, active 2nd century, author. | Comite de traduction Padmakara, translator. Title: The Root Stanzas of the Middle Way: the Mulamadhyamakakrik / Nagarjuna; Translated from the Tibetan by the Padmakara Translation Group. Other titles: Madhyamakakrik.

English Description: First Shambhala Edition. | Boulder: Shambhala, 2016. | Previously published privately in a limited edition in France by Editions Padmakara (2008). Identifiers: LCCN 2015041715 | eISBN: 978-1-9220-5998-7 | ISBN 9781611803426 (paperback) Subjects: LCSH : Mdhyamika (Buddhism)Early works to 1800. | BISAC : RELIGION / Buddhism / Sacred Writings. | PHILOSOPHY / Buddhist.

Classification: LCC BQ 2792.E5 P33 2016 | DDC 294.3/85dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041715 The Padmakara Translation Group gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Tsadra Foundation in sponsoring the translation and preparation of this book. O f Nagarjunas life, we know almost nothing. He is said to have been born into a Brahmin family in the south of India around the beginning of the second century CE . He became a monk and a teacher of high renown and exerted a profound and pervasive influence on the evolution of the Buddhist tradition in India and beyond. Much of his life seems to have been spent at Sriparvata in the southern province of Andhra Pradesh, at a monastery built for him by king Gotamiputra, for whom he composed the Suhrllekha, his celebrated Letter to a Friend. Nagarjuna is intimately associated with the Prajnaparamita sutras, the teachings on the Perfection of Wisdom, the earliest-known examples of which seem to have appeared in written form around the first century BC , thus coinciding with the emergence of Mahayana, the Buddhism of the Great Vehicle.

It is recorded in the Pali Canon that the Buddha foretold the disappearance of some of his most profound teachings. They would be misunderstood and neglected, and would fall into oblivion. In this way, he said, those discourses spoken by the Tathgata that are deep, deep in meaning, supramundane, dealing with emptiness, will disappear.of the Mahayana believed that, with the Prajnaparamita scriptures, they were recovering a profound and long-lost doctrine. Nagarjuna seems to have been deeply implicated in this rediscovery. Questions of historicity aside, the story that he brought back seven volumes of the Prajnaparamita sutras from the subterranean realm of the nagas, where they had been preserved, conveys a clear message. In the eyes of Nagarjunas contemporaries and of later generations, the appearance of the Prajnaparamita sutras marked a new beginning in the history of Buddhism, and yet the teachings they contained were not innovations.

And in their interpretation and propagation, Nagarjuna played a crucial role. Tibetan scholarship has organized Nagarjunas literary output into three collections. The first of these, the so-called Yukti-corpus (Tib. rigs tshogs) contains six scholastic texts expounding the Madhyamaka view and related topics: the Mulamadhyamakakarika (The Root Stanzas on the Middle Way), the Yuktishashtika (The Sixty Stanzas on Reasoning), the Shunyata-saptati (The Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness), the Vigrahavyavartani (Answers to Objections), the Vaidalya-sutra (The Finely Woven Sutra), and the Ratnavali (The Jeweled Necklace) or the no longer extant Vyavaharasiddhi (The Proof of Conventionalities). The second collection is the Stava-corpus (Tib. gtam tshogs), which contains letters and other discourses. gtam tshogs), which contains letters and other discourses.

It is impossible here to give anything approaching an adequate description or analysis of the Mulamadhyamakakarika. Yet as a brief indicator of its importance, we may say that, together with Nagarjunas other philosophical writings, it was the first-known attempt to distill the voluminous contents of the Prajnaparamita scriptures into a systematic scholastic form. As such it lies at the origin of the Madhyamaka school, which flourished in India from the second century CE until the disappearance of Buddhism from the subcontinent in the twelfth: a thousand years during which the tradition was upheld by a series of outstanding teachers and commentatorsof whom Aryadeva, Buddhapalita, Bhavaviveka, Chandrakirti, Shantideva, Shantarakshita, Kamalashila, and Atisha were only the most notable. Shantarakshita and Kamalashila introduced the Madhyamaka teachings to Tibet, where they have formed an essential cornerstone of Buddhist study and practice until the present day. The Mulamadhyamakakarika is an extremely demanding text. It is filled with subtle reasoning on abstruse themes.

Without the help of the commentarial tradition as well as a keen and tenacious commitment on the part of the student, it is practically incomprehensible. As one tries to negotiate the labyrinthine arguments, however, it may be useful to bear the following four points in mind. The first is that, however tortuous and rarefied the karikas may seem, it is worth remembering that Madhyamaka is not a mystical doctrine concerned with strange and otherworldly revelations. Neither is it a philosophical explanation of Reality, if by that is meant some remote transcendental absolute. The purpose of Madhyamaka is simply to elucidate the nature of phenomena: the things and situations that make up the world of our experience. The second point is that Madhyamaka is not a species of philosophical nihilism.

Although phenomena are said to be empty, their functional effectiveness on the experiential level is not at all called into question. Phenomena appear and they do affect us regardless of the theories that we may entertain about them. The view of Madhyamaka, on the other hand, is that within phenomena, two truths, the relative and ultimate, fuse together and are united. Relatively, things appear through the force of causes and conditions. Yet, in the very moment of their appearance, they are empty of intrinsic being: the seemingly solid, discrete, independent thingness that, owing to our long-ingrained tendency to perceive them thus, appears to us so vividly. The third point is thatlike all Buddhist teachingsMadhyamaka has one essential goal: the liberation of beings.

Next page

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.  Buddha Shakyamuni

Buddha Shakyamuni  Bodhisattva Manjushri

Bodhisattva Manjushri  Nagarjuna T HE R OOT S TANZAS OF T HE M IDDLE W AY The Mulamadhyamakakarika Nagarjuna TRANSLATED FROM THE TIBETAN BY THE Padmakara Translation Group

Nagarjuna T HE R OOT S TANZAS OF T HE M IDDLE W AY The Mulamadhyamakakarika Nagarjuna TRANSLATED FROM THE TIBETAN BY THE Padmakara Translation Group

Shambhala Publications, Inc. 4720 Walnut Street Boulder, Colorado 80301 www.shambhala.com 2008 by Editions Padmakara Previously published privately in a limited edition in France by Editions Padmakara (2008). Cover design: Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Cover art: Cover painting of Nagarjuna by Livia Liverani used courtesy of Tsadra Foundation.

Shambhala Publications, Inc. 4720 Walnut Street Boulder, Colorado 80301 www.shambhala.com 2008 by Editions Padmakara Previously published privately in a limited edition in France by Editions Padmakara (2008). Cover design: Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Cover art: Cover painting of Nagarjuna by Livia Liverani used courtesy of Tsadra Foundation.