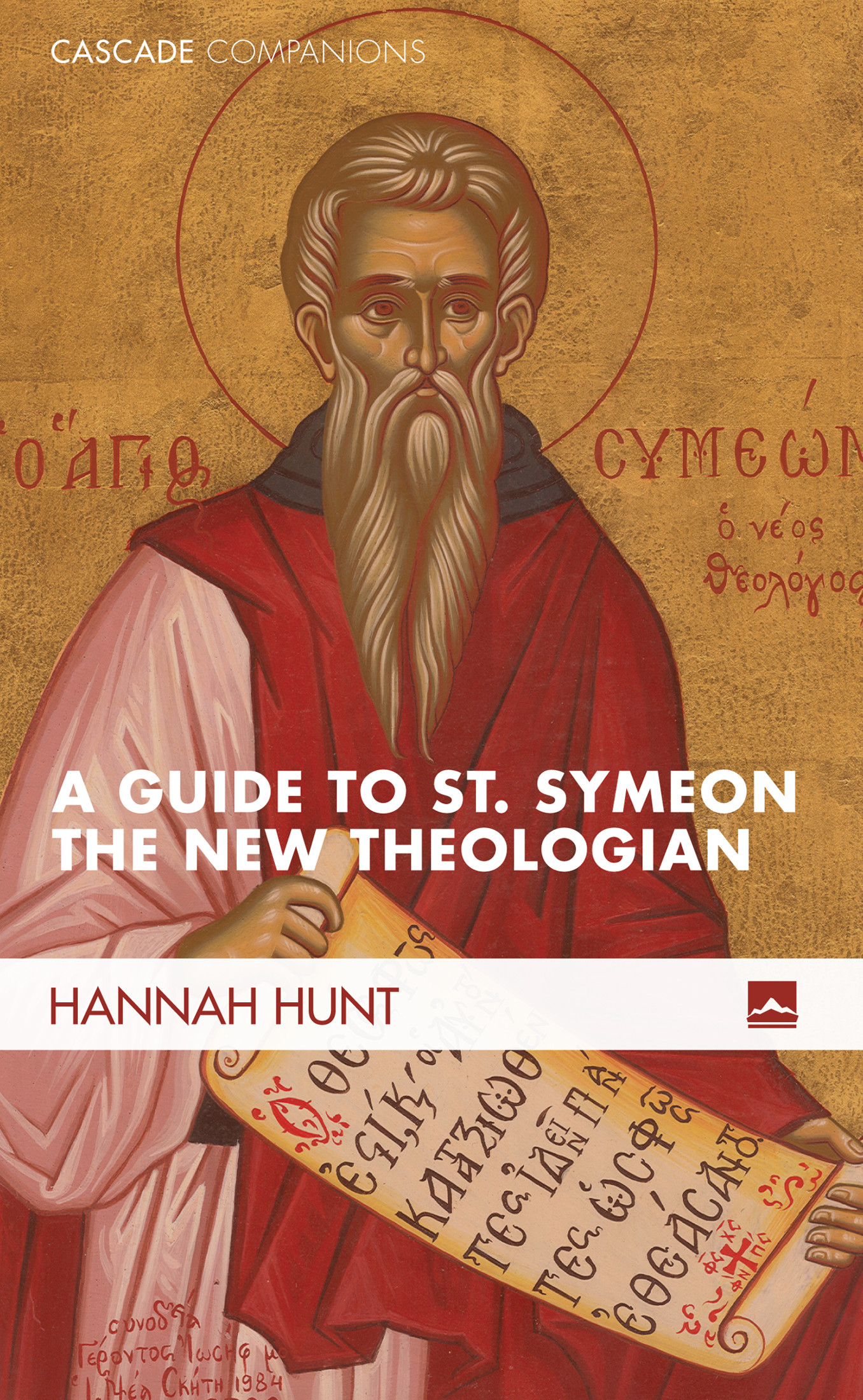

Cascade Companions

The Christian theological tradition provides an embarrassment of riches: from Scripture to modern scholarship, we are blessed with a vast and complex theological inheritance. And yet this feast of traditional riches is too frequently inaccessible to the general reader.

The Cascade Companions series addresses the challenge by publishing books that combine academic rigor with broad appeal and readability. They aim to introduce nonspecialist readers to that vital storehouse of authors, documents, themes, histories, arguments, and movements that comprise this heritage with brief yet compelling volumes.

titles in this series:

Reading Paul by Michael J. Gorman

Theology and Culture by D. Stephen Long

Creationism and the Conflict over Evolution by Tatha Wiley

Justpeace Ethics by Jarem T. Sawatsky

Reading Bonhoeffer by Geffrey B. Kelly

Christianity and Politics in America by C. C. Pecknold

Philippians in Context by Joseph H. Hellerman

Reading Revelation Responsibly by Michael J. Gorman

forthcoming titles:

The Rule of Faith by Everett Ferguson

one

Historical Context to St. Symeon the New Theologian

Sources for Symeons Life

Written evidence for Symeons life and times derive from two key sources, neither of them very objective to modern eyes. The first is a biography or vita by his pupil and disciple Nicetas Stethatos. The obvious problem with an account by someones own pupil, especially in a religious context, is that it is likely to be hagiographic , in other words it will overemphasize the holiness and virtue of its subject. This can be done by manipulating the facts, omitting or overemphasizing some, to create a particular picture of the revered person. Stethatos, who ended up as Abbot of the Stoudios Monastery, claimed that towards the end of Symeons life the old man effectively appointed him as his literary heir. Just as the younger Symeon had a vision of his spiritual father, Eulabes, so in turn Symeons pupil had a vision of his mentor; thirteen years after he had died Symeon appeared to Nicetas in a dream, requesting that he write the story of his life and publish his writings.

In addition to the biography, there is also a great deal of evidence about his life smuggled into his own writings, where he sometimes uses the pseudonym, George (which may have been his baptismal name) as a disingenuous attempt to disguise his identity. Not much is known about Symeons early life. He was born in Paphlagonia, an area of Asia Minor between Galatia and the Black Sea, probably around CE. His family was aristocratic, and being ambitious for a courtly career for their son it is possible the lad was castrated, as some court positions were only available to eunuchs. The status of eunuchs (and whether or not Symeon became one) is contentious within the church and debated by historians: in part, it was presumed that being unable to father children, a eunuch would remain loyal to his employer. At the age of eleven, he was removed from the family home and sent to the court under the protection of his uncle.

The young man apparently progressed within the Byzantine civil service, experiencing an abrupt interruption to the family patronage, which had placed him in court when his uncle was murdered during the civil war in 963. It is barely possible to separate the demise of his political career from the emergence of his enthusiasm for the religious life. For well born men in the Byzantine court the monastery was already a place of refuge, refreshment, and advice; having the right spiritual father added to your social standing, and even those people who took public office might, when they felt the need, consult with an advisor in a monastery. Such a practice is still common for modern Orthodox Christiansand can cause controversy as we shall see in chapter 6. For centuries there had been a sense in Byzantine society that monasteries were a spiritual powerhouse, and that having a saint or holy man in your town or village was a benefit to everyone. So it was not unusual that Symeon went occasionally to a local monastery for counsel. He started to visit the Studite monastery in the capital on an occasional basis. In his Discourse Symeon describes how George, who lived in the city of Constantinople and led a normal worldly existence, encountered a monk who started to guide him towards spiritual reading appropriate for monastic formation. Symeon records how One day, as he stood and recited, God, have mercy upon me a sinner... suddenly a flood of divine radiance appeared from above and filled all the room. (The prayer Symeon was reciting is known as the Jesus Prayer in the Eastern Christian tradition, and it is widely used today for private devotion.) Like St. Paul on the road to Damascus, Symeon loses awareness of his surroundings and in this ecstatic condition has a vision of light surrounding the saint of whom we have spoken, the old man equal to angels, who had given him the commandment and the book. As we shall see in chapters 4 and 5, penitent but joyful tears and visions of light are ways in which Symeon measures the authenticity of a mystical encounter with God. It is on this basis that he claimed his spiritual father Eulabes was a saint and that even though he was not ordained it was such men who had demonstrably had a direct encounter with God, who had the power to remit sins that were confessed to them.

Important as this encounter was, he did not immediately leave his position in the Imperial court, and in fact the years he spent as an adolescent in the opulent surroundings of the palaces of Constantinople provided him with a treasury of images he later used to contrast the indulgent life of court to the ideal, ascetic life. There are many references in his writings to the splendors of the Byzantine court where he had been a minor official; the light-filled palaces with their rich hangings; the encounters with the emperor that parallel biblical parables; even the purple robes of the imperial family, which are, he reminisces, merely a pale imitation of the divinity of Jesus expressed by the royal purple of his blood shed for all sinners.

Writing retrospectively, as did Augustine, Symeon gives thanks that God gave him the free will to turn his back on his debauched past and that God grabbed him by the hair of his head, dragging him out of the filthy ditch of his wrongdoings. The image of being soiled is continued when he describes how Christ effectively handed him over to Eulabes, in a besmirched condition, still wholly defiled, with my eyes, my ears, and my mouth still covered with mud. This represented his sensual engagement with the pleasures of the world. In his account, Christ instructs Symeon to Hold on to this man, cleave to him and follow him, for he will lead you along and wash you. He entered the Studite monastery where Abbot Peter placed him under the care of Eulabes. For the first year he slept under the steps of the elders cell.

Early Monastic Formation

It is hard to be certain of all the factors in Symeons change of direction at this point in his life. Going into the monastery meant leaving his life at the court where he had held a role of some responsibility in the civil service. As a child he had benefitted from the patronage of an uncle who was in the imperial court, and like other adolescents away from home, he enjoyed indulging in the normal dissipations of a comfortably off young man. As suggested above, it is also possible that his move away from the court was due to the death of his uncle in the backlash against aristocracy encouraged by the young emperor, whose advisor during his minority had also not favored aristocrats. Byzantine society at the time was dominated by a handful of very influential and well-connected wealthy families and Basils unease with this situation can be traced through the legislation he undertook to undermine their power. So political disappointment, or even recognizing the need to keep a low profile, may have contributed towards the young Symeons change of direction.