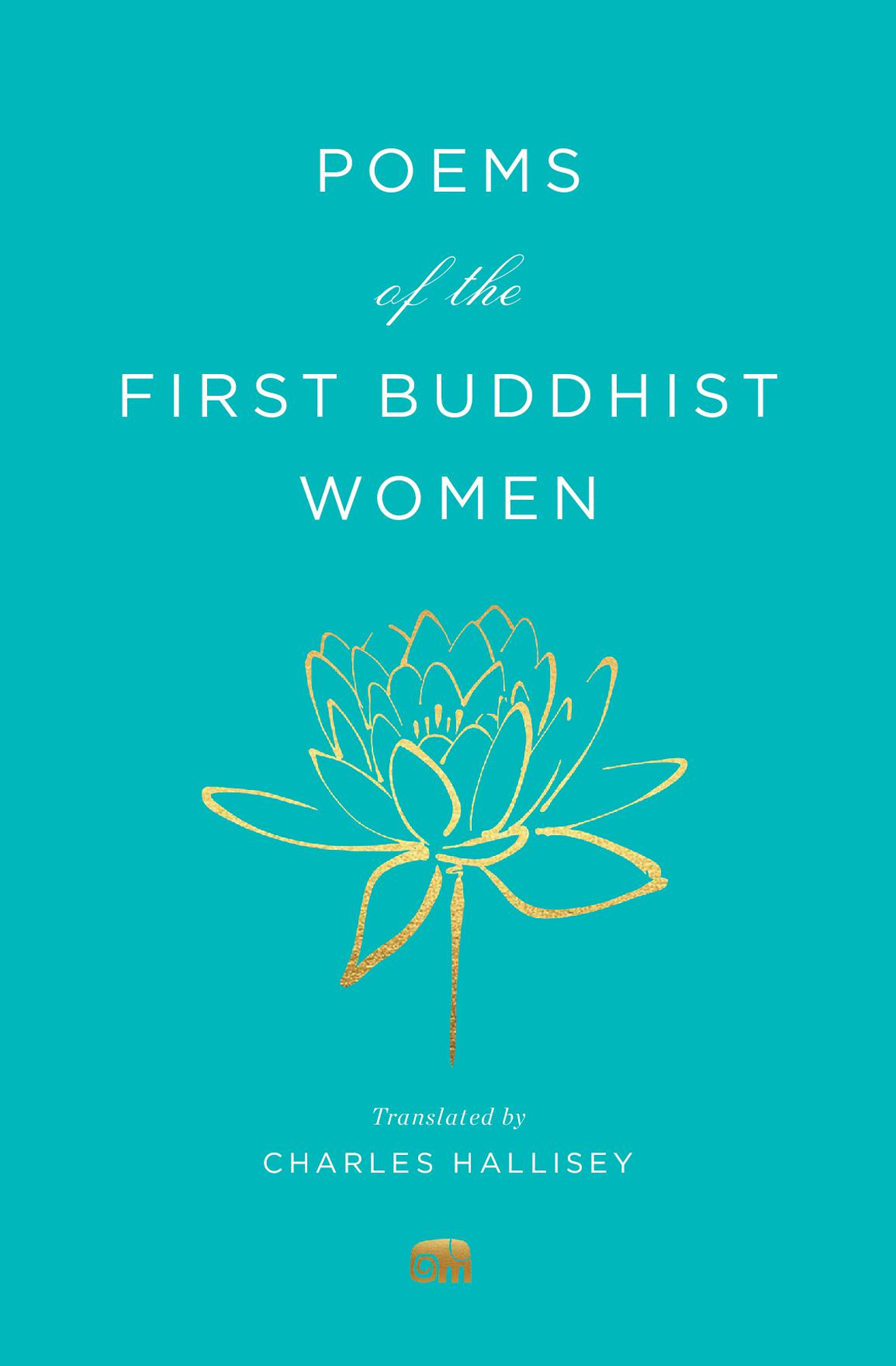

First published in Murty Classical Library of India, Volume 3, Harvard University Press, 2015.

Names: Hallisey, Charles, 1953- translator.

Title: Poems of the first Buddhist women : a translation of the Therigatha / translated by Charles Hallisey.

Other titles: Therigatha (Harvard University Press) | Tipiaka. Suttapiaka. Khuddakanikya. Thergth. | Murty classical library of India.

Description: New edition. | Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2021. | Series: Murty classical library of India | Includes bibliographical references | Identifiers: LCCN 2020034185 | ISBN 9780674251359 (paperback) | ISBN 9780674251410 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Buddhist poetry. | Pali poetry. | Pali poetryTranslations into English.

The Thergth is an anthology of poems by and about the first Buddhist women. These women were thers, senior ones, among ordained Buddhist women, and they bore that epithet because of their religious achievements. The thers in the Thergth are enlightened women and most of the poems (gth) in the anthology are the songs of their experiences. Dhammapala, the sixth-century Buddhist commentator on the Thergth, calls the thers poems udna, inspired utterances, and by doing so, he associated the Thergth with a venerable Buddhist speech genre. For Dhammapala, the characteristic mark of the utterance would be one or more verses consisting of knowledge about some situation accompanied by the euphoria that is felt there, for an udna is proclaimed by way of a composition of verses and caused to rise up through joy and euphoria.

As salt just seems to go with food, the adjective first and the Thergth seem to go together. It is easy to see why. It is an anthology of poems composed by some of the first Buddhists; while the poems are clearly nowhere near as old as the poetry of the g Veda, for example, they are still some of the first poetry of India; the Thergths poems are some of the first poems by women in India; this is the first collection of womens literature in the world. As such statements suggest, to use the adjective first is to point to something key to the value that these poems have for us. We often try to draw out that value by turning our attention to the religious, literary, and social contexts in which the poems were composed and then try to see the Thergth as expressions of those contexts. It is important, however, to ask when we think of the poems as first in these different ways, whether we may be inadvertantly predetermining how we approach the work. While reading and appreciating the Thergth for being the first of so many things is no doubt appropriate, we also want to ask ourselves if seeing the Thergth in this way also predisposes us to read the poems mainly for their historical information and whether this might come at the expense of their expressive, imaginative, and emotional content, as well as their aesthetic achievements.

Reading the Thergth as Poetry

The Thergth is not merely a collection of historical evidence of the needs, aspirations, and achievements of some of the first Buddhist women. It is an anthology of poems. They vary in quality, to be sure, but some of them deserve not only the adjective first in a historical sense; they also deserve to be called great because they are great literature.

They are literature in the way that Ezra Pound meant when he said, Literature is news that STAYS news. The poems in the Thergth are about that freedom. They are udnas about the joy of being free, and they hold out the promise, in the pleasure that they give, of being the occasion for making us free, too.

How a literary text from more than two millennia ago can give us pleasure, can speak to us about ourselves and about our world in astonishingly fresh and insightful ways, is not easy to explain, but there is no doubt that the poems of the Thergth have proved capable of doing so. Moreover, there is no doubt that they are capable of giving pleasure in translation.

This was probably the case throughout the long history of the Thergth. The imprint of linguistic difference and translation seems intrinsic, especially in the difficulties and peculiarities that many of the verses present. Individual poems were composed over a considerable period of time, perhaps centuries; according to Buddhist tradition, they date from the time of the Buddha himself, while according to modern historical methods, some date as late as the end of the third century B.C.E.

The poems as we receive them are in Pali, the scholarly and religious language distinctive to the Theravadin Buddhist traditions that are now found in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia; in the first millennium, however, Theravada Buddhism was quite prominent in south India as well. It seems very likely that these verses have been translated from whatever their original versions may have been in any number of ancient Indian vernaculars and then reworked as Pali evolved. The translation of the poems in the Thergth into Pali was key to their wide circulation. The anthology has continued to work its magic in modern translations, including into German by Karl Eugen Neumann in 1899, into Bangla by Bijay Chandra Majumdar in 1905, and into Sinhala by the novelist Martin Wickramainghe.

For Wickramasinghe, the road to pleasure, so basic to receiving the deeper meanings of the Thergth, would open up for a reader who took the time to remember that these verses must be read with a sensibility that is guided by the poetry itself. What does a sensibility guided by poetry itself look like, and how might it be brought to bear when reading the Thergth? Taking the first verse from the poem of Ambapali as a case study can help us see the kind of richness and pleasure that comes when we take the Thergth seriously as poetry:

The hairs on my head were once curly,

black, like the color of bees,

now because of old age

they are like jute.

Its just as the Buddha, speaker of truth, said,

nothing different than that.

If we read primarily for information, we could justifiably say that this poem is about the central Buddhist teaching on impermanence. In Buddhist thought, impermanence is one of the three marks (tilakkhaa) of the world, along with suffering (dukkha) and the lack of an enduring essence (anatt): everything in this world, including our bodies, disappoints us and causes us to suffer because everything changes in ways we do not want; everything changes because everything in the world is impermanent (