John Dewey

and Daoist Thought

SUNY series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture

Roger T. Ames, editor

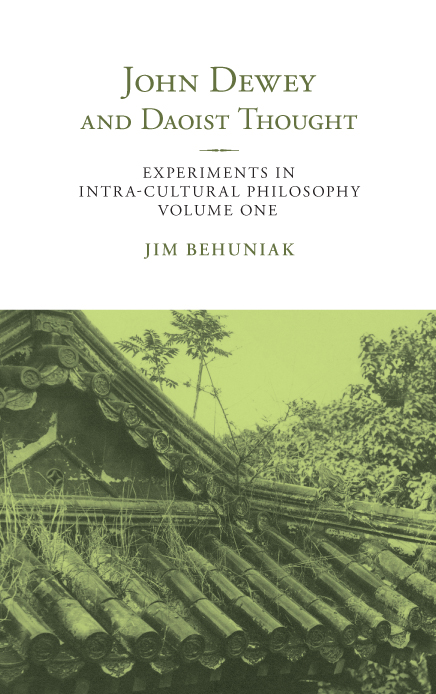

John Dewey

and Daoist Thought

Experiments in Intra-cultural Philosophy

Volume One

Jim Behuniak

Front cover: Roofline image taken by John Dewey in China.

Back cover: Image of John Dewey (Peking, July 5, 1921), courtesy of the Morris Library, Special Collections Research Center, Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2019 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Behuniak, James, author.

Title: John Dewey and Daoist thought / Jim Behuniak.

Description: Albany : State University of New York, [2019] | Series: Experiments in intra-cultural philosophy ; volume one | Series: SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018033271 | ISBN 9781438474496 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438474502 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438474519 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Dewey, John, 18591952KnowledgeTaoist philosophy. | Dewey, John, 18591952TravelChina. | Taoist philosophy. | Philosophy, Chinese. | Philosophy, Comparative. | East and West.

Classification: LCC B945.D44 B393 2019 | DDC 191dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018033271

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Anna

Contents

Illustrations

Prelude

John Dewey retained a keen and personal interest in young Chinese students even after his retirement from Columbia. Consequently, his influence on the Chinese people is deep-rooted because it is two-foldthrough his teachings and through his personal contact with hundreds of young Chinese who pride themselves on being his friend.

Meng Chih to William H. Kilpatrick, September 16, 1949

Deweys Chinese Friendships

When John Dewey died in 1952 at the age of 92, few people knew that he had adopted a Chinese son. Sing-nan Fen (19162011) was born in Suzhou, one of the oldest cities in the Yangzi basin and one known for its lovely flowered gardens, elegant canals, and stone bridges. While a student in China, Fen became a self-taught specialist in American philosophy. He translated Josiah Royces The Spirit of Modern Philosophy into Chinese along with several of Deweys articles. As Dewey later remarked, He read some of my philosophical works for translation into Chinese while still in China and all on his own got a much more adequate idea of their purport and tenor than most college students here. Fen earned a Boxer Indemnity Fellowship in 1946 and came to the United States to study at the University of Chicago. Unhappy with his classes at Chicago, he spent most of his time reading Dewey instead, using hundreds of index cards to organize his notes. Fen wrote to the world-famous philosopher, expressing his admiration and sending him some of his own philosophical essays. Dewey was instantly impressed, and wrote back to Fen encouraging him to transfer to Columbia.

When Dewey learned that his good friend, Joseph Ratner, would be in Chicago, he asked him to pay a visit to Sing-nan Fen. Ratner advised him on transferring to Columbia, which Fen did the following year. Upon his arrival in New York City, Dewey invited the young man to a dinner party at his home. Fen can relate what happened next:

My first visit to Deweys apartment was a disaster. The Deweys served cocktails before dinner. I was physiologically allergic to hard liquor. To be polite, however, I took all the drinks they offered. Gradually I felt dizzy, sick, ran to bathroom and became unconscious until the next morning on the sofa in the living room. When I woke up, the sweet old man sat beside me and offered me breakfast. I thought that was the end of our beautiful friendship. But that was the beginning of my being adopted to Deweys family.

The two would remain like father and son for the rest of Deweys life. Their surviving letters convey the depth of their communion. Dewey would address Fen as his Son and sign his letters, With Love, Father, and Pa Dewey. Johnny and Adrienne, Deweys legally adopted children, took to calling Fen their Brother. He became part of the family.

Dewey supported and mentored Sing-nan Fen during his years at Columbia. Fen visited Dewey regularly, went on country outings with the family, visited ice cream parlors with the kids, and vacationed with the family at their Maple Lodge retreat in Pennsylvania. Dewey read and commented on Fens PhD dissertation, An Examination of the Socio-Individual Dichotomy as it Relates to Educational Theory , which was submitted to Teachers College in March 1949. The work was primarily concerned with restoring continuity between nature and culturea concern that Dewey shared with Fen. This was the period in which Dewey had come to see culture rather than experience as the natural context in which human behavior is expressed. Culture, Dewey realized, is nature. As Fen would argue in his dissertation: cultural behaviors are objectively naturalas a tree grows, as a volcano erupts, as a stone falls, as a dog runs.

Dewey sought out opportunities for Fen, wrote him letters of support for his job applications, and suggested to him topics for papers. Something about Chinese [philosophy] in relation to Chinese culture would be good, Dewey proposed, an article on how Americanor more generally Western philosophy strikes a [Chinese student] would hit a popular note. Fen focused mainly on issues relating to his study of American philosophy, educational psychology, and pragmatic naturalism, and he produced a series of original articles. Alain Locke took notice of the quality of his work and hired Fen to his first teaching job at Howard University in 1950.

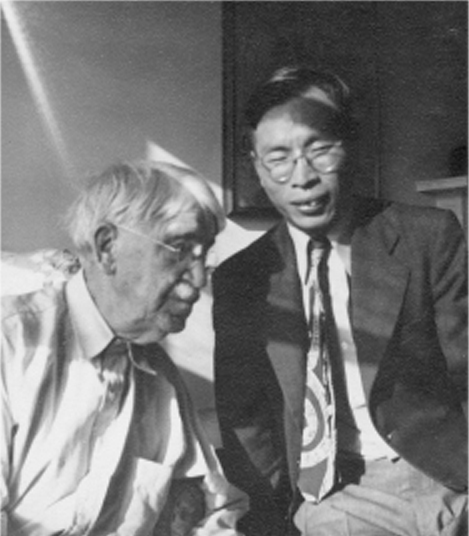

Figure 0.1. John Dewey with Sing-nan Fen, date unknown. Courtesy of Ruth Fen.

Deweys affinity with Chinese students was more than academic. He genuinely enjoyed having Chinese company and went out of his way to make Chinese friends. In 1922, he and his first wife, Alice, invited a group of Chinese students to join them for Easter weekend on their farm in Long Island. The

Throughout his life, Dewey committed himself to the improvement of USChina relations. His fellow Americans, he believed, understood too little about Chinese culture. As Meng Chih remembers, Dewey was troubled by this absence in the Columbia community of a reciprocal understanding of China. This concern led Dewey to cofound the China Institute in 1926. Today, it remains the oldest non-profit organization in the United States devoted to fostering cross-cultural understanding with China. Its original mission remains an important one: to disseminate information concerning Chinese and American education; to promote a closer relationship between Chinese and American educational institutions through the exchange of professors and students; to assist Chinese students in America in their educational pursuits; to help American students interested in the study of things Chinese; and to stimulate general interest in America in the study of Chinese culture.