John Dewey

and Confucian Thought

SUNY series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture

Roger T. Ames, editor

John Dewey

and Confucian Thought

Experiments in Intra-cultural Philosophy

Volume Two

Jim Behuniak

Front cover: Roofline image taken by John Dewey in China.

Back cover: Image of John Dewey (Peking, July 5, 1921), courtesy of the Morris Library, Special Collections Research Center, Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2019 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Behuniak, James, author.

Title: John Dewey and Confucian thought / Jim Behuniak.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2019] | Series: Experiments in intra-cultural philosophy ; Volume two | Series: SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018033272 | ISBN 9781438474472 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438474465 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438474489 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Dewey, John, 18591952KnowledgePhilosophy, Confucian. | Dewey, John, 18591952TravelChina. | Philosophy, Confucian. | Philosophy, Chinese. | Philosophy, Comparative. | East and West.

Classification: LCC B945.D44 B39 2019 | DDC 191dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018033272

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Anton

Contents

Illustrations

Interlude

Dewey is still in Chinalearning, I hope, from the Chinese.

Lewis Mumford to Patrick Geddes, May 5, 1921

Deweys Chinese Dinners

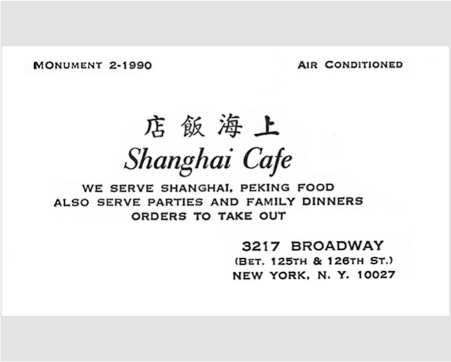

Tucked under the elevated local tracks at Broadway and 125th Street in Manhattan, Shanghai Caf opened its doors in 1949. It was the first non-Cantonese Chinese restaurant to open in New York and remains widely remembered as one of the best Chinese restaurants that the city has ever seen. Thus, in the last few years of Deweys life, the area around Columbia became a hub for what were then known as Mandarin restaurantsbasically any non -Cantonese Chinese cuisine.

Gradually, the Shanghai Caf on Broadway and 125th came to be known as the Old Shanghai Caf to distinguish it from its eponymous competitors. Dewey and his family dined there every Sunday night and Sing-nan Fen often joined them. Lawrence Cremin, one of Fens classmates at Teachers College, came to join these dinners by accident. As he explains:

Fen asked me quite unexpectedly one evening whether I would be willing to deliver a package for him to the Dewey apartment on my way home, and I said of course I would I went on up and rang the bell and Mrs. Dewey came to the door and graciously accepted the package and asked whether I would like to meet Professor Dewey. I said it would be a privilege and was promptly ushered into the study, where Dewey was pecking away at an ancient typewriter, using two fingers. He looked up, smiled, greeted me warmly, said he was working on an article dealing with the improvement in his concept of interaction that the term transaction made possible, and then asked quite bluntly, What do you think, Mr. Cremin? It was one of those occasions when the lips move but the words have trouble coming out. The words did come, and the point is [that] we had a lively conversation for about a half-hour, in which at the age of twenty-three I was treated as an absolute equal I shall never forget it.

From then on, Cremin was on the Invite list for Deweys Chinese dinners. I must tell you, writes Cremin, that whatever the emphasis on the social and communal in Deweys writings, it was rampant individualism in that Chinese restaurant. Eating was the main event, and Dewey did not defer to his underlings. I may be the only person living who learned to use chopsticks fighting over fried rice with John Dewey, reckons Cremin.

Dewey became adept at using chopsticks during his Asia trip, while also solidifying his affection for Chinese food. Prior to leaving San Francisco for Asia, he and Alice put in the requisite preparations. Last Friday we went to Chinatown again for dinner so that Papa and Mama could get used to using chopsticks, Sabino Dewey relates to Lucy. They are doing fine, he reports

Figure 0.1. Business card of the original Shanghai Caf, date unknown. Image source: https://www.chowhound.com/post/remember-shanghai-cafe-126th-broadway-196905#photo=1060802.

Deweys first letter from China is all about food. I will tell you something of what we had to eat, he writes to his children. On the table were little pieces of sliced ham, the famous preserved eggs which taste like hard boiled eggs and look like dark colored jelly, and little dishes of sweet shrimps, etc. So the description begins. We had chicken and duck and pigeon and veal and pigeon eggs in soup and fish and little oysters nice little vegetables and bamboo sprouts mixed in with the others, and we had shrimps cooked and sharks fin and birds nest. So it rolls to its conclusion: For dessert we had little cakes made of bean paste filled with almond paste and other sweets.

One month later, there would be the following to report: I am going right on getting fat on delicious Chinese food.

So the founding of the Peoples Republic of China in 1949 would have one salutary effect on Deweys life: it allowed him to end his days in New York surrounded by excellent Chinese food. He did not let the opportunity pass. Dewey was always eating in some Chinese restaurant or another. He once ran into Hu Shihs son in a Chinese restaurant, Lovers of Chinese food can relate. Fine cuisine is one of the myriad ways in which cultures take what is basically a common biological requirementin this case, eating and elevate it through human intelligence and creativity. China achieves this as well as any culture in the world.

Like every cultural showcase, fine cuisine emerges against the background of a shared human nature. Stemming from our earliest forest diets, humans have always had a preference for sugars and acids, cravings that

Nevertheless, humans gather around the table to share what is by and large a common pleasure in artfully prepared food. Taste is only part of it. On the strictly metabolic level, our bodies require the same carbohydrates, proteins, sugars, and amino acids that other animal bodies require. We convert these into raw energy and through transduction use the nutrients to replace damaged cells. Unlike that of many other animals, human metabolism is normally running at maximum capacity. The reason is that 16 percent of our basal metabolism is allocated to our brains, whereas the average mammal allocates only 3 percent. This makes us unusual, because in the economy of life, animals are under selection pressure to be as dumb as they can get away with. Through such natural endowments we forge relationships, communicate, engage in ritualized behavior, create art and music, and prepare the delectable xiaolongbao that Dewey enjoyed on Sunday evenings at the Old Shanghai Caf. Appreciating the continuity ( yi ) of such experiences with the rest of Nature ( tian ) will be the central theme in the present volume.