Published in Great Britain by

Kuperard, an imprint of Bravo Ltd

59 Hutton Grove, London N12 8DS

www.kuperard.co.uk

Enquiries:

Copyright 2009 Bravo Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Publishers.

Series Editor Geoffrey Chesler

eISBN: 978-1-85733-642-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Cover image: Detail from a coloured engraving of Zhou Wenjus original painting A Literary Garden. Southern Tang, tenth century. Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

Image on Georges Jansoone, reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution licence 3.0

v3.1

Contents

List of Illustrations

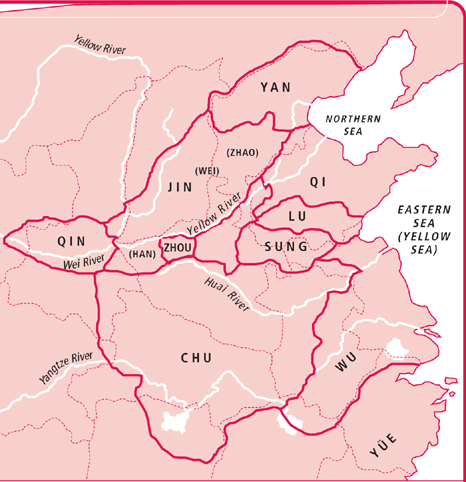

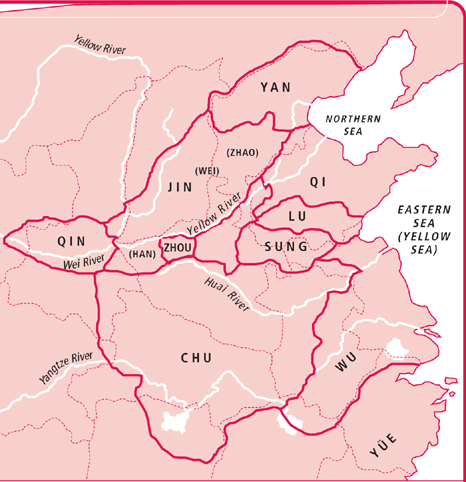

Territories of the Warring Statesc. 500 BCE

Introduction

In recent years, China has emerged as a superpower and Westerners have suddenly had to come to terms with a powerful nation whose ancient civilization owes little to outside influences. For the West, China has been remote in many ways. We have felt its culture to be alien, its people inscrutable. Its language, and particularly its writing system, are totally different from our own. To understand modern China we need to overcome our sense of otherness and appreciate what lies behind the way in which Chinese people think.

Historically, Europeans have long benefited from Chinese inventions and discoveries paper, silk, porcelain, the compass and gunpowder, to name but a few. It is often held that these practical developments sprang from Daoism, one of the main strands of early Chinese philosophy. The Daoists believed that Man should follow the grain of nature rather than cut across it, and in the course of discovering what this grain was they investigated natural forces and materials, and experimented widely to find out how these could be utilised. Their respect for nature resonates strongly with the ecological ideas of today.

Another strand of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism, was more concerned with the relationships between people, and saw its task as working out how a populous society could live in harmony. Confucius and his followers argued for a system of mutual respect, where each individual owed duties to some and responsibilities to others, in a social order where, indeed, no man was an island. Individualism would be subordinated to the good of the community, and all people would be provided for.

The third main strand of Chinese philosophy was Buddhism: a late arrival on the scene in historical terms, but one that focused on Mans relationship to the cosmos. It succeeded in China because of its resonance with philosophical Daoism, but the Buddhist concept of compassion for all creation added the extra dimension of Mans relationship to Man to the Daoist quest to understand the Unchanging Way and the virtue of wu-wei, which means achieving without exertion.

The complex interaction of these philosophical traditions came to influence all aspects of life in China. They continue even under Communism to underpin much of Chinese thinking and behaviour. The study of Chinese philosophy will bring even greater rewards than the expediency of doing so. The wealth of Chinese thought and literature is not of historical or intellectual interest only. It contains profound insights into the human condition and offers challenging perspectives on our place as humans in society, in nature and in the cosmos.

Chapter 1

The Earliest Traces

In approaching the story of Chinese philosophy, it is important to be aware that an identifiably Chinese culture has had a documented existence that spans some 4,000 years. Indeed, there are even older archaeological traces which suggest that its roots may extend at least 2,000 or 3,000 years further back than that, so Chinese cultural patterns pre-date the existence of a single political entity that can be called China, since the unified state only came into being in 221 BCE . For convenience, however, we shall use the term China as a convenient shorthand to describe the geographical area now known as China, and Chinese to identify its inhabitants.

As in many cultures, there were those in China who tried to work out the ways in which individuals should conduct themselves and rulers should govern the people. From the earliest times, scholars and teachers who developed philosophical thought were aware of traditional occult systems, so philosophy and religious thought became intertwined in a cultural environment which they thought extended back to a legendary era. As the development of philosophical thought in China was mainly concerned with matters of government and social organisation, the three strands of philosophy, religion and politics were woven together, sometimes close-knit and sometimes more loosely associated. Moreover, within each strand there were competing views.

This ongoing blend of influences, and the relative importance of each strand at any time, can be traced throughout Chinese history right up to the present day, and so in following the story of Chinese philosophy we shall be touching on archaeology, history, geography, philosophy, religion, statecraft and politics, to discover how the philosophy developed and how China in the twenty-first century is still influenced by this remarkable continuity of culture and thought.

Geography

The geography of China ensured that the development of society took place in substantial isolation from the rest of the world. To the east and south-east lay the China Sea and the Pacific, to the north lay the steppes and tundra, to the west and north-west there were the central Asian deserts, to the west loomed Tibet and the Himalayan range, and to the south-west the jungles provided another natural barrier to free travel and migration.

The Archaeological Evidence

Against this backdrop, the first Neolithic settlements grew up in the Yellow River valley in north China. As evidence to support the assertion that the development of Chinese culture rose in isolation, archaeological excavations have yielded stone tools of a different pattern from that of Western tools. The tools found in China have a distinctive cutting edge formed by chipping from both faces of the tool, compared with the chipping from one face typical of the West.

Neolithic culture (c. 70002000 BCE ) became quite widespread, extending from sites in modern-day Gansu province, where painted red pottery was found, to Longshan near the mouth of the Yellow River and sites as far south as Hangzhou below the Yangtze River, where a distinctive black pottery has been excavated. Despite the differences in the manufacturing process that resulted in the different colours of the body of the ceramics, however, the detailed stylistic features of the wares indicate that they come from a generally uniform cultural background.