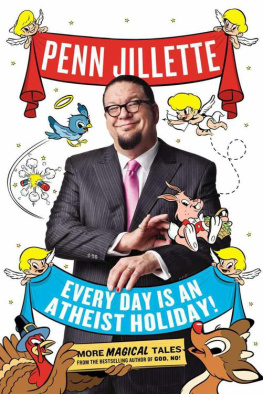

Humorists vs. Religion

Critical Voices from Mark Twain to Neil DeGrasse Tyson

IAIN ELLIS

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3401-2

2018 Iain Ellis. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover images of apples versus oranges 2018 dobrinov/iStock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Introduction

To paraphrase Mark Twain, reports of the death of the culture wars have been greatly exaggerated. Looking back from 2018, the Obama years are sometimes seen through rose-colored glasses as a time when American society experienced an inexorable march toward improved civil rights in regard to race, gender, and sexuality, identity zones within which, in decades prior, the religious right regularly contested. Even the long march toward the legalization of marijuana became a blitzkrieg during this period, with little opposition put forth from the Moral Majority forces that once fought such decadent developments with righteous indignation. Where were the prayer in schools or anti-abortion rallies that gave voice to Jerry Falwells Evangelical army during the Reagan era? Where were the Terri Schiavo and Intelligent Design equivalents, sagas that rallied those same forces during the Bush 43 years? In short, where had the religious right gone? Had it waved the white flag, leaving the culture wars to the battlefields of a bygone era?

Judging by recent developments, the religious right went nowhere; it was merely in hibernation, awaiting the next opportunity to re-emerge on the frontlines of the culture. That opportunity has now knocked, as we see activist fundamentalists filling the highest seats of the Trump administration. Since Obama vacated the White House, they have, one might say, come out of the closet and into the cabinet.

This disquieting turnaround has left many culture observers somewhat red-faced, especially those that published their state of the nation musings between 2008 and 2016. Richard T. Hughes, a professor of religion at Messiah College, argued in 2009 that Americans had grown Bush-weary by the end of his second term, and that young Evangelicals were turning away from the socio-political concerns that had once animated them.

For those living through 2018 America, these predictions appear premature, if not out of step with reality. Yet, despite the signs up ahead that indicate imminent onslaughts against science, minority groups, and secular institutions, a credible argument might still be made that the current administration represents a temporary blip, an anomaly in a broader trajectory toward a more humanist future. Those optimistic of such a macro-trend are heartened by the enormity of the backlash against Trump and his cast of culture warriors. Although emanating from various sources, these counter-reactions have been led, driven, and sustained with the greatest force, determination, and effectiveness not by the media or opposing political parties but by our nations critical humorists. Now, as they have before, public humorists have taken the fight to those political theocrats attempting to impose their beliefs and values or to restrict others of theirs.

While culture war skirmishes between humorists and religion can be traced back to (and beyond) the satirical output of the likes of Aristophanes and Juvenal (in Ancient Greece and Rome, respectively), a significant and pertinent date for American history is 1859, the year Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Not only did this belief-shaking book embolden scientists to explain the history of the world in ways and means that wholly undermined scriptural gospels, but it also established principles of evidence and reason for anyone explaining that history. Ever since, David Niose states, the culture wars have raged in one form or another in popular culture.

Darwin and evolutionary theory not only set religious fundamentalists against the scientific community, but also against its humorist sympathizers. Michael Billig explains that the concept of a sense of humor came into vogue during the same period of American history; this trait was perhaps best embodied and embraced at the time by Mark Twain, a writer many consider the nations greatest (humorist). Twain was intellectually inspired by Darwin, and his wit was often unleashed on religious institutions and individuals of his time, whether it be for their Gospel of Wealth prosperity theology, their imperialist advocacy of Manifest Destiny, or their willful ignorance about evolution in the face of mounting scientific evidence.

If scientists bore the brunt of the early culture wars, Twain too was an early combatant, always armed with a rapier wit and a gleeful willingness to use it. His largely secular perspectives were out of sync with the mainstream beliefs of the 19th century, but they were not wholly alien. The Founding Fathers, a century earlier, were mostly Deists, interested in the teachings of Jesus but rarely with the supernatural aspects of religion. Paine, Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, and Madison were all Deists, skeptics, or atheists, products of the Enlightenment thinking of Hobbes, Locke, Hume, and Rousseau. All stressed the importance of reason, empiricism, and science. Such philosophy inspired the Founding Fathers to establish the wall of separation between church and state they deemed necessary for a viable democracy to function. For Jefferson et al., the dark ages of church abuses, arbitrary authority, and faith-based customs were an anathema to a nation seeking life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all its citizens. Such a vision for America has not always been fully embraced by certain religious-political forces, but it has remained the working precedent most political representatives have followed, if sometimes grudgingly.

Although the wall of separation still stands, it has periodically been chipped at and rocked back and forth. One such time was in 1925, the year of the Scopes Trial, then hailed as the trial of the century. Scopes brought festering conflicts between Darwinists and creationists to a head into a legal showdown over whether the teaching of evolution violated Tennessee law. The creationists and state won the battle in court, but it is often assumed that they lost the subsequent war at the national level. For historians Edward J. Larson and Andrew Hartman, such an historical reading is only partially true. The former says that it is a myth to suggest that the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial halted the anti-evolution movement. activity during those decades ultimately intensified the culture wars when they resumed in the battle royals later in the century.

Looking back, the Scopes Trial and its aftermath represent an important indicator that the culture wars would be regarded as a long-term fight for fundamentalists, a group that might periodically retreat into their trenches, but only to re-arm, not to surrender. Scopes also introduced us to one of the most renowned early combatants from the humorist camp, H.L. Mencken. His caustic dismissal of the creationists as Neanderthal brought a style of put-down insult humor to journalism that fellow anti-theist fighters like Christopher Hitchens would later adopt and adapt.

Next page