Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

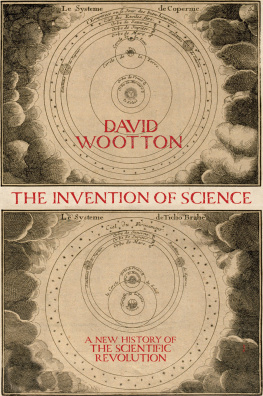

POWER, PLEASURE,

and

PROFIT

Insatiable Appetites from Machiavelli to Madison

DAVID WOOTTON

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

2018

Copyright 2018 Railshead Ltd.

All rights reserved

Book design by Dean Bornstein

Jacket art: Allegory of Happiness, painting by Agnolo Bronzino (1564). Courtesy of the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy, and Bridgeman Images

Jacket design: Tim Jones

978-0-674-97667-2 (alk. paper)

978-0-674-98990-0 (EPUB)

978-0-674-98989-4 (MOBI)

978-0-674-98988-7 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Wootton, David, 1952 author.

Title: Power, pleasure, and profit : insatiable appetites from Machiavelli to Madison / David Wootton.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018023374

Subjects: LCSH: Conduct of lifeHistory. | Power (Social sciences)History. | ValuesHistory. | Enlightenment. | AmbitionHistory. | Pleasure. | Profit.

Classification: LCC BJ1595 .W793 2018 | DDC 170.9/03dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018023374

For Alison, with whom I have found happiness

Ragione di Stato, from Cesare Ripa, Iconologia (4) (1603).

Contents

It is an opinion of the ancient writers, that men are wont to vex themselves in their crosses, and glut and cloy themselves in their prosperity, and that from the one and the other of these two passions proceede the same effects: for at what time soever men are freed from fighting for necessity, they are presently together by the eares through ambition; which is so powerfull in mens hearts, that to what degree soever they arise, it never abandons them. The reason is, because nature hath created men, in such a sort, that they can desire every thing, but not attaine to it. So that the desire of getting being greater then the power to get, thence growes the dislike of what a man injoyes, and the small satisfaction a man hath thereof. Hereupon arises the change of their states, for some men desiring to have more, and others fearing to lose what they have already, they proceede to enmities and warre.

Niccol Machiavelli, Discorsi sopra la prima Deca di Tito Livio (trans. Edward Dacres, 1636)

Besides this, the desire of man being insatiable [sendogli appetiti umani insaziabili] (because of nature hee hath it, that hee can and will desire every thing, though of fortune hee be so limited, that he can attain but a few) there arises thence a dislike in mens minds, and a loathing of the things they injoy, which causes them to blame the times present and commend those passd, as also those that are to come, although they have no motives grounded upon reason to incite them thereto.

Niccol Machiavelli, Discorsi sopra la prima Deca di Tito Livio (trans. Edward Dacres, 1636)

O human mind, insatiable and vain,

Fraudulent, fickle, and, above all things,

Impious, malignant, full of quick disdain!

Niccol Machiavelli, Tercets on Ambition

From whence, then, arises that emulation which runs through all the different ranks of men, and what are the advantages which we propose by that great purpose of human life which we call bettering our condition? To be observed, to be attended to, to be taken notice of with sympathy, complacency and approbation, are all the advantages which we can propose to derive from it. It is the vanity, not the ease or the pleasure, which interests us.

Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)

The principle which prompts to save, is the desire of bettering our condition, a desire which, though generally calm and dispassionate, comes with us from the womb, and never leaves us until we go into the grave. In the whole interval which separates those two moments, there is scarce perhaps a single instant in which any man is so perfectly and compleatly satisfied with his situation, as to be without any wish of alteration or improvement of any kind. An augmentation of fortune is the means by which the greater part of men propose and wish to better their condition.

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776)

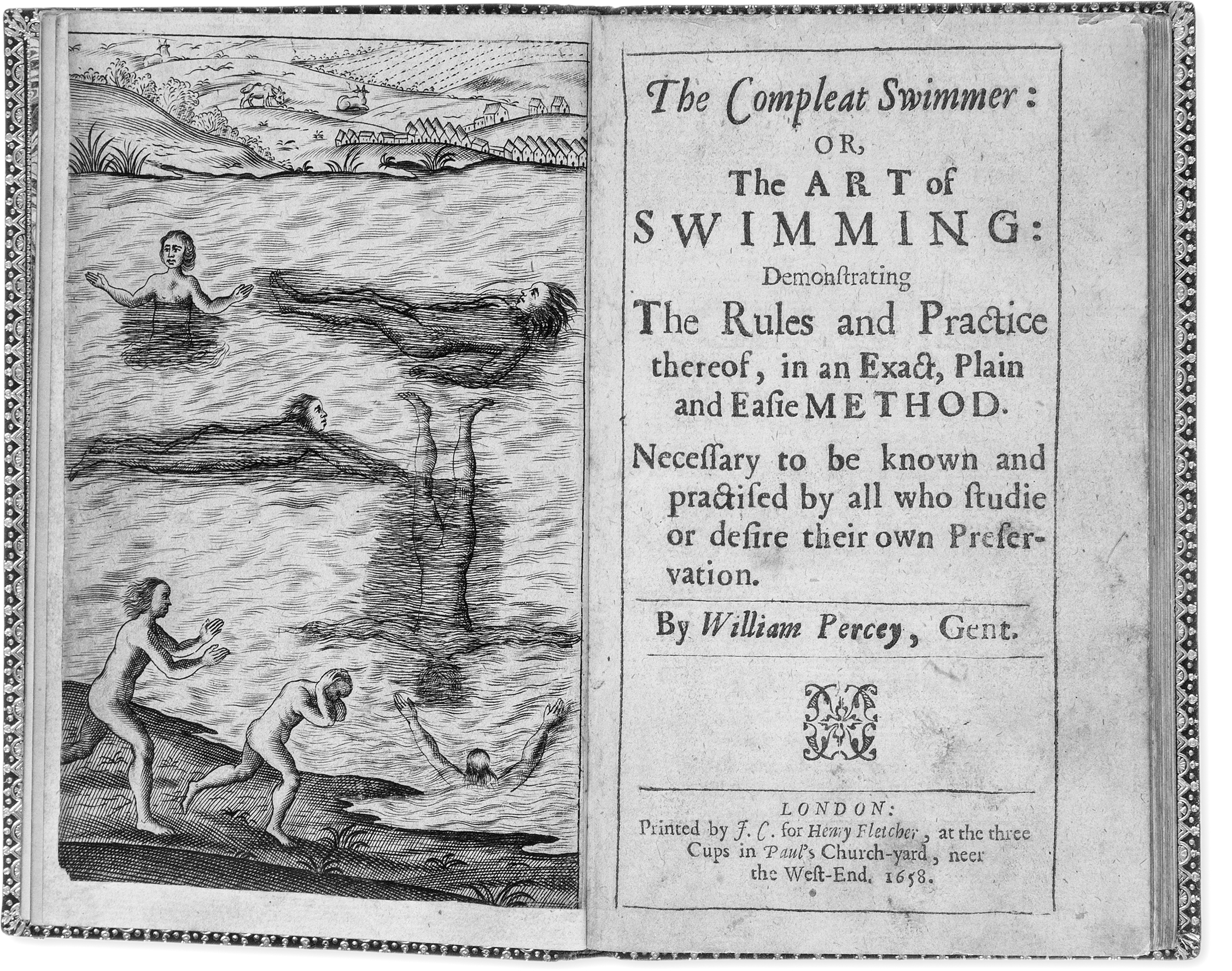

Title page and frontispiece from William Percey, The Compleat Swimmer (8) (1658).

William Perceys The Compleat Swimmer (1658) begins, as I do, by addressing the ingenious, prudent, and self-preserving reader. For Percey, There are two onely chief ends, which are the only inducements to all Actions in the whole world; and these are pleasure and profit; yea these are the mayn and only objects whereon all Creatures animal or rational fix their eyes; the wheeles upon with [sic: which] all our Actions turn, as the Universe doth upon the Axletree, these are the Magnets or Loadstones that attract all our thoughts and actions to themselves as their Centre. Whether he intended to or not, Percey was presenting a new account of what it is to be a human being. He even went so far as to suggest that human beings are little different from the animals:

Doth not the indefatigable Emmet [Ant] keep still exercising his restless motion all the summer, that he may enjoy the pleasure and profit thereof in his low-roof, but to himself, and his un-aspiring thoughts, a delightful Palace. What incessant pains takes the Laborious Bee, that she may enjoy the sweetness of the Hony in the Artificial Chambers of her well-wrought Castle? Herein consists pleasure and profit both. Sed quid moror istis? [But why do I linger over such examples?] The prudent and industrious Merchant Roames far and neer, spares neither costs nor pains, danger,care nor trouble; and all for the sacred hunger of Gold: Therein consists both his pleasure and profit too. Nay, the Toyl-embracing husband-man [farmer] merrily whistles along the tediousness of his painful furrows, in hopes to rejoyce in a fruitful Harvest.

He may well have had classical philosophers such as Epicurus and Lucretius in mind, but no classical philosopher (and indeed no medieval theologian) had praised hard labor in this way, or taken economic activity as the paradigmatic example of rational activity. Something new is happening here, yet Percey seems quite unaware of it, and assumes that his readers will think as he does.

Percey is an early example of the conviction that human beings (and animals too) are always engaged in the pursuit either of immediate pleasure or of the means to future pleasure.