Contents

Guide

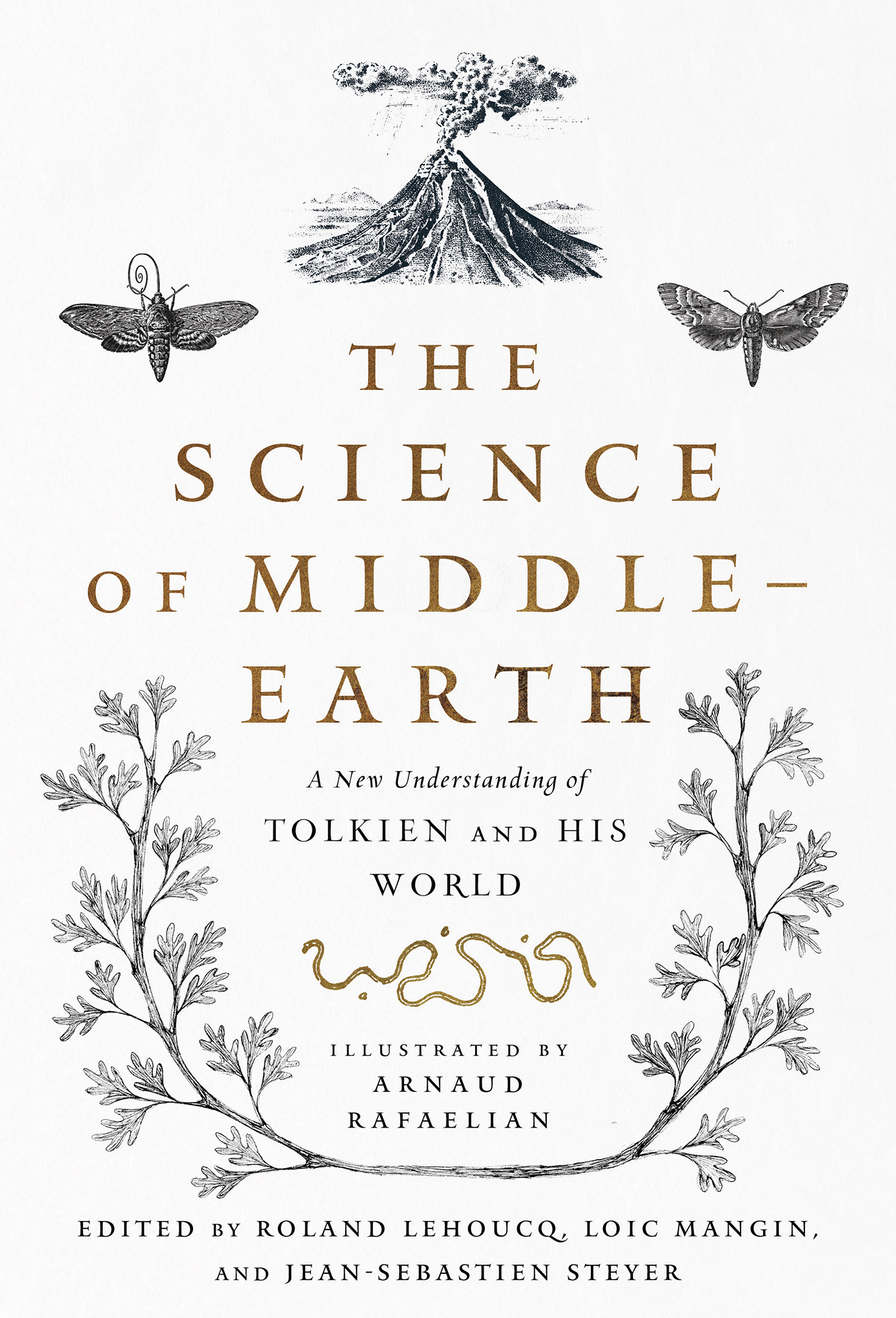

The Science of Middle-Earth

A New Understanding of Tolkien and His World

Illustrated by Arnaud Rafaelian

Edited by Roland Lehoucq, Loic Mangin, and Jean-Sebastien Steyer

Dedicated to my brother Jean-Claude (June 7, 1954 to September 7, 1973).

THE SCIENCE OF MIDDLE-EARTH

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2021 by Roland Lehoucq, Loc Mangin, and Jean-Sbastien Steyer

Illustration Copyright 2021 by Arnaud Rafaelian

Translation Copyright 2021 by Tina Kover

First Pegasus Books cloth edition April 2021

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Front cover image Shutterstock

Jacket design Studio Gearbox

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-616-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-64313-617-2

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

www.pegasusbooks.com

TOLKIEN, LORD OF THE SCIENCES

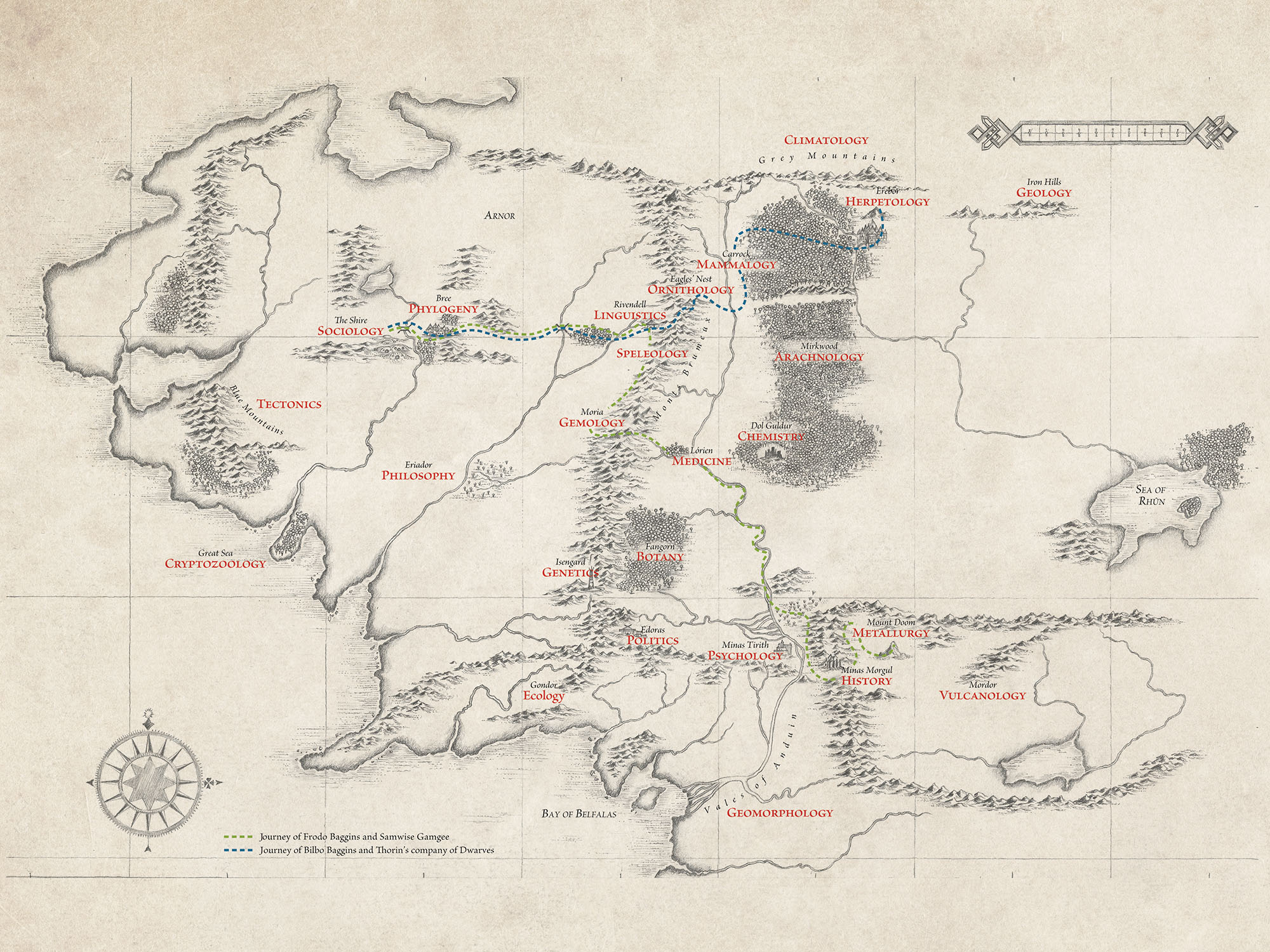

ow are the Elvish language and Old English related? What is the geology of Middle-earth? How does the dragon Smaug fly? You dont need to be a scientist or a Tolkien specialist to answer these questions; all you have to do is open this book.

ow are the Elvish language and Old English related? What is the geology of Middle-earth? How does the dragon Smaug fly? You dont need to be a scientist or a Tolkien specialist to answer these questions; all you have to do is open this book.

In 1937, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien left an indelible mark on the history of fantasy with The Hobbit, originally written for his children. The multitalented author, Oxford university professor, philologist, and poet would repeat this success with his best-known works, including The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955) and The Silmarillion (published posthumously in 1977). Passionate about mythology and languages, which he entertained himself by inventing, Tolkien left behind a complex legendarium, an imaginary world so rich, fully formed, and elaborate that it serves as an outstanding argument in favor of science as entertainment! That is the goal of this book: to use Tolkiens universeits history, languages, geography, monsters, and charactersto speak about the human, physical, and natural sciences. We are well aware of how many themes there are to be explored, how many questions raisedbut, though we cannot be exhaustive, we hope to be reader-friendly, and to share knowledge with a wide audience. We have no desire to shatter the fantasy of Tolkiens creation, much less to criticize the man himself; rather, we hope to show how the sciences can enrich the world. Welcome to the Middle-earth of science! A cross-disciplinaryand sometimes undisciplinedjourney through the land of Tolkien And if you [come back], you will not be the same!

R OLAND L EHOUCQ , L OC M ANGIN, AND J EAN -S BASTIEN S TEYER

TOLKIEN AND THE SCIENCES: A RELATIONSHIP WITH MANY FACES

ISABELLE PANTIN, historian, cole normale suprieure

olkien saw himself primarily as a poet and a creator of myths through words, but he was certainly just as much a scientist, if we keep to a fundamental (and therefore timeless) definition of science: the rational effort made to learn about and understand natural reality, from the organization of the cosmos to human activity and production. If, on the other hand, we limit ourselves to the standard (caricatural?) definition of modern Western science, dominated by models created by and for physics and mathematics, and engaged in a conquering approach based on technology, the analysis demands far greater nuance. We must, then, examine these two approaches separately.

olkien saw himself primarily as a poet and a creator of myths through words, but he was certainly just as much a scientist, if we keep to a fundamental (and therefore timeless) definition of science: the rational effort made to learn about and understand natural reality, from the organization of the cosmos to human activity and production. If, on the other hand, we limit ourselves to the standard (caricatural?) definition of modern Western science, dominated by models created by and for physics and mathematics, and engaged in a conquering approach based on technology, the analysis demands far greater nuance. We must, then, examine these two approaches separately.

Tolkien had a scientific mind in the broadest sense: not the kind defined by the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, perhaps, or by others for whom the aptitude for objective knowledge could not exist before the advent of the modern era, but rather that of Plato, Aristotle, and Roger Bacon (12141294), that insatiably curious admirable doctor who had preceded him at Oxford, albeit some seven centuries earlier and occupying a different chair. Tolkien loved the real world, and he was curious about it, and wanted to have an unbiased relationship with it; endowed with a sharp critical mind, he maintained a cordial loathing for the sort of convoluted, pretentious discourse on any subject which offered false access to knowledge while simultaneously acting as an opaque and deceptive barrier.

A REFUSAL TO LIE ABOUT REALITY

To express his disgust for pretense, Tolkien often used the word bogus, meaning cheap and artificial, and often associated with trickery and fraud. He uses it, for example, in a 1968 letter to Time-Life International (Letters, no. 302), in which he declines to have a series of photos taken in a work setting, pointing out that he and the agency clearly have different definitions of the word natural; as he is never photographed while writing or speaking with someone, a snapshot of him pretending to be at work would be entirely bogus. The term is used here to refer to writerly practices, but it is applicable to various sciences as well.

In his study of the Kalevala, Tolkien points out that this collection of ancient Finnish poems, compiled and arranged from oral sources with great care by the physician and linguist Elias Lnnrot in the 19th century, is unsullied by the bogus archaism that marks the work attributed to Ossian (a mythical third-century A.D. Gaelic poet) by the man who claimed to be its translator, James Macpherson.)

Bogus syndrome can also afflict those who affect an ivory-tower purism in matters of botanical terminology, like those pedantic proofreaders of The Lord of the Rings who substituted nasturtium (the Latin name of the flowering plant also known as Indian Cress) for its true English name, nasturtian. In a letter written in July 1954, Tolkien cites the expertise of Merton Colleges gardener and rejects nasturtium as bogusly botanical and falsely learned.

The disorder had a far more serious effect on certain champions of the Indo-European hypothesis and its biased application to the study of mythology. Georges Dasent (18171896), a leading author of Scandinavian studies who did not hesitate to express in his work his belief in the superiority of the Nordic race (which, to him, included the English), was accused by Tolkien, in his essay

ow are the Elvish language and Old English related? What is the geology of Middle-earth? How does the dragon Smaug fly? You dont need to be a scientist or a Tolkien specialist to answer these questions; all you have to do is open this book.

ow are the Elvish language and Old English related? What is the geology of Middle-earth? How does the dragon Smaug fly? You dont need to be a scientist or a Tolkien specialist to answer these questions; all you have to do is open this book. olkien saw himself primarily as a poet and a creator of myths through words, but he was certainly just as much a scientist, if we keep to a fundamental (and therefore timeless) definition of science: the rational effort made to learn about and understand natural reality, from the organization of the cosmos to human activity and production. If, on the other hand, we limit ourselves to the standard (caricatural?) definition of modern Western science, dominated by models created by and for physics and mathematics, and engaged in a conquering approach based on technology, the analysis demands far greater nuance. We must, then, examine these two approaches separately.

olkien saw himself primarily as a poet and a creator of myths through words, but he was certainly just as much a scientist, if we keep to a fundamental (and therefore timeless) definition of science: the rational effort made to learn about and understand natural reality, from the organization of the cosmos to human activity and production. If, on the other hand, we limit ourselves to the standard (caricatural?) definition of modern Western science, dominated by models created by and for physics and mathematics, and engaged in a conquering approach based on technology, the analysis demands far greater nuance. We must, then, examine these two approaches separately.