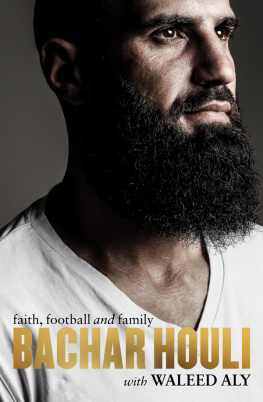

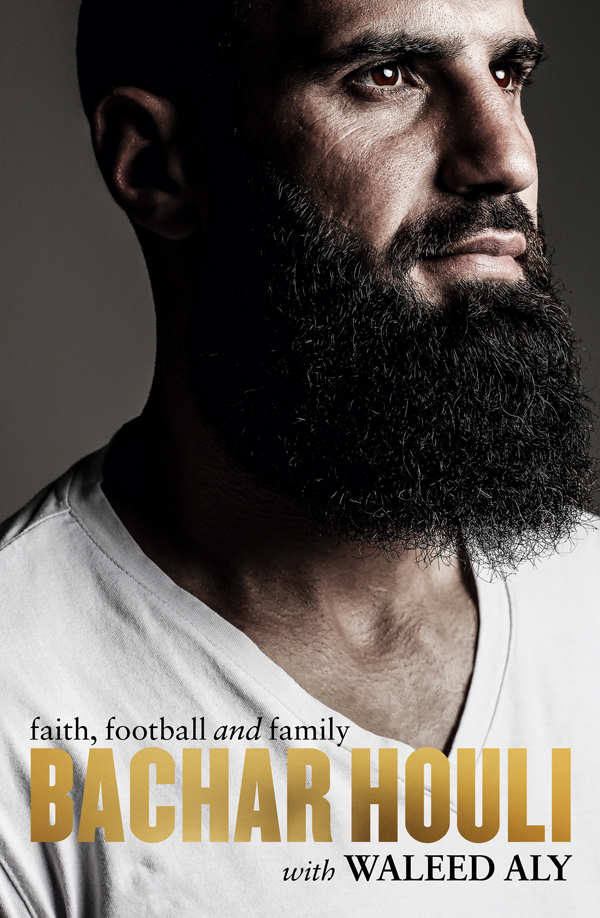

About the Book

Bachar Houli is as accomplished an AFL footballer as they come. Hes been part of two Richmond Premiership sides, he was an All-Australian in 2019, and with more than 200 games to his name he remains a key part of a champion team.

Picked at number 42 in the 2006 National Draft by Essendon, Houli played 26 games for the Bombers before moving in 2010 to Tigerland, where rookie coach Damien Hardwick was assembling the team that six years later would achieve the seemingly impossible and claim Richmonds eleventh Premiership. Another flag followed two years later, with Houli close to best on ground in both deciders.

Yet its as the AFLs most prominent Muslim player that Houli is best known and his strong Muslim values and the importance of family are at the heart of the man he is. Writing for the first time, Houli explores the experiences and beliefs that sparked and sustained his trailblazing success as a Muslim footballer, and that established him as a leading voice within the AFL community for inclusion, understanding and tolerance.

Co-authored with acclaimed broadcaster and writer Waleed Aly, Bachar Houli: Faith, Football and Family tells the unique story of one of footballs most fascinating men.

For my family and community who have ridden every bump.

For those who are different, who know that being different isnt a roadblock but an advantage.

For my heroes who are striving for that great off-field premiership of unity and solidarity in our society.

This is for you.

FOREWORD

Bachar Houli made his first speaking appearance at a school as an Essendon player in his first week on the job. A young man at the back of the class began talking disruptively. Bachar called him to the front and made him apologise to his classmates. But Bachar wasnt finished. Now promise me youll go home tonight and tell your mum and dad you love them, he said.

I first heard this story from an AFL employee in early 2007, just before Bachar made his debut. It had become quietly famous in those parts because no one had seen anything quite like it before. Who was this guy? Which 18-year-old kid who has barely even attended a training session as an AFL player, let alone played a game, does something like this? I loved the story then for exactly the same reason I love it now: it captures Bachar in miniature.

First, its so fantastically Lebanese. Family looms very large in Lebanese culture, and love and respect for parents are probably the crowning feature. Even the most misbehaving child will submit to this idea. People might go astray in many ways, but someone who is rude to or neglectful of his or her parents is truly lost. So when Bachar chose to conclude this moment like this, he wasnt doing something off-beat or beside the point. He was turning to what, for him, was the obvious and natural full stop. He was reminding the boy of one of the most foundational, anchoring principles he could think of directing him to remember who he was, to consult his moral compass and reorientate himself.

But there was also a lightness to it, because Bachar had changed the subject to something on which he presumed everyone agreed. Bachar didnt even bother to ask whether or not the boy loved his parents that was assumed, because anything else was unthinkable. The only necessary reminder was for the boy to tell them. I imagine him saying it in the way a parent might say, after reprimanding their young child, Now, go on outside and play. Its even a touch playful I think of Bachar rustling the boys hair as he speaks.

Its inevitable that family is a major theme in this book. Its not deliberately this way; it just pours forth when Bachar starts talking about his life. To talk to him even briefly is to understand that family is among the things he values most. To talk to him at length is to discover how profoundly it infuses every aspect of his story. Its at the heart of his decision to take up football as a kid, and his progression to the highest level of the game. Its central to his deepest relationships in football, with people like Damien Hardwick, Ivan Maric and Trent Cotchin. Its the thing that allowed him to meet, and then court, Rouba, who became his wife.

Wherever you look in Bachars story theres an aunty, or an uncle, or a friend who might as well be. Theres a sibling, or a cousin, or a Lebanese neighbour whose relationship with Bachar is thoroughly fraternal. You might think these people are all similar. Theyre not. They are diverse in age, in temperament, in their attitudes towards life. This is probably the key to understanding Bachar. He knows who he is and what he believes, but hes comfortable around people who are thoroughly different, because he spent his childhood forming thick, life-defining bonds with them. And hes mature beyond his years because he has spent his life with older people. When Bachar addressed that school group in his first week as an AFL player, he was 18 on paper, but more like 28 in spirit. That was why he exuded an easy authority.

But probably the most remarkable aspect of the classroom encounter is that hes there at all. Hed have been forgiven, at that age, for being consumed with figuring out how to survive his first few training sessions, and yet he was making himself available for community work. But then, Bachar walked into an environment that made his whole career a form of community work. He must be the most hyped number 42 draft pick in AFL history. Even before his debut, his media file would comfortably have matched that of Bryce Gibbs or Tom Hawkins, the highest-profile draftees from his year. There was no doubt Bachar could play; his press was more a function of social curiosity, as he was the first practising Muslim selected to play at the highest level. There is an argument that the attention was overblown. At one level, that is unquestionable. But wasnt that true of almost every news story with a Muslim protagonist at the time?

Bachar was drafted in 2006, little over a year after the London Tube bombings, which introduced the notion of homegrown terrorism to the public imagination. Four months later, the Operation Pendennis raids in Melbourne and Sydney franked that fear, part of the biggest counter-terrorism investigation in Australian history, which led eventually to eighteen terrorism convictions. This was a time of heightened, frenzied, public anxiety about multiculturalism, and especially about young Muslim men. Bachar had simply walked into that zeitgeist. In a troubled time, he was an ambassador by circumstance, irrespective of choice. He knew that before he was even drafted.

I remember the Friday night in May 2007 when Bachar made his AFL debut against North Melbourne. I remember feeling, as I walked into what was then called the Telstra Dome, that something momentous was happening. I remember being nervous, like I had something major at stake. And I suppose, like so many Australian Muslims, I did. The AFL is a unique stage in Australian society. Muslims had been cast as villains on so many public stages for so long. This felt like a rare opportunity for one of us to be cast as a hero. I remember seeing Bachar line up next to Michael Firrito, who seemed twice his size in every direction, and thinking he just looked so out of place. But he wasnt. And that was the whole point.