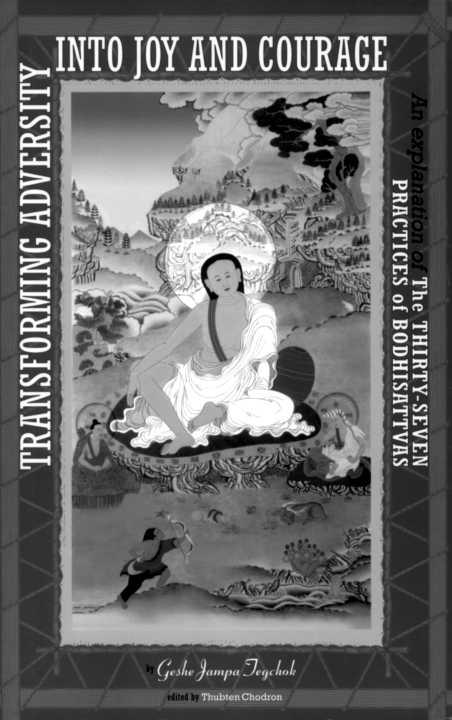

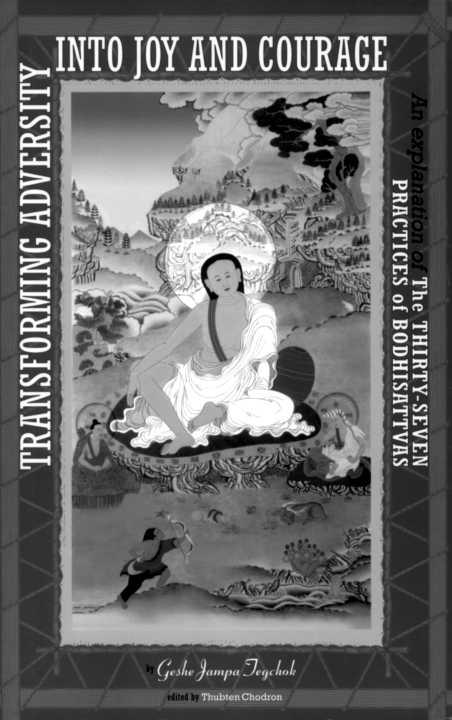

TRANSFORMING ADVERSITY

INTO JOY AND COURAGE

TRANSFORMING ADVERSITY

INTO JOY AND COURAGE

An Explanation of the Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas

by

Geshe Jampa Tegchok

Edited by Thubten Chodron

CONTENTS

23 33 47 63 67 85 101 113 121 155 165

PREFACE

The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas, by the Tibetan monk Gyalsay Togme Sangpo, is a text popular in all schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Studied by old and young, monastics and lay followers, it describes, in thirty-seven short verses, the essential practices leading to enlightenment. Gyalsay Togme Sangpo (1295-1369) was renowned as a Bodhisattva in Tibet and revered for living in accordance with the Bodhisattva ideals and practices that he taught. He continuously practiced exchanging oneself with others and transforming adverse circumstances such as sickness and poverty into the path to enlightenment, and in this way inspired not only his direct disciples but also generations of practitioners up to the present day.

In the late 1980s, while he was abbot of Nalanda Monastery in France, Geshe Jampa Tegchok, who is currently the abbot of Sera-je Monastic University in India, gave a commentary on The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas. Born in 1930, Geshe Tegchok became a monk at the age of eight. He studied the major Buddhist treatises at Sera-je Monastic University in Tibet for fourteen years before fleeing his homeland in 1959 following the abortive uprising of the Tibetans against the Chinese communist occupation of their country. After staying in the refugee camp at Buxa, India, Geshe Tegchok went to Varanasi, where he obtained his Acharya (Master) Degree and taught for seven years. He then began teaching in the West-three years in England and ten years at Nalanda Monastery in France. In 1993, His Holiness the Dalai Lama appointed him as abbot of Sera-je Monastic University in India.

I had the good fortune to study with Geshe Tegchok for three years in the early 1980s and was delighted when he asked me some years later to prepare his oral teachings for publication. Having received teachings almost daily from Geshe-la, I know that he teaches very clearly and with deep care and compassion for his students. While teaching, he often explores a topic in detail, revealing aspects that would remain hidden in a more cursory teaching. This commentary is no exception.

Geshe Tegchok teaches in a very strict, yet relaxed manner. He never waters down the meaning to make it more acceptable to our ego. For me, a good spiritual mentor is one who challenges my preconceptions, who makes my ego squirm with discomfort when its games are exposed. At the same time, Geshe-la is relaxed and jovial, laughing with his students as we study and discuss a text together. But his good humor doesn't prevent him from introducing us to a very subtle type of analysis. He reveals multiple layers of meaning inside seemingly simple concepts.

As editor, I was repeatedly faced with deciding what to include and what to delete from Geshe-la's oral teachings. He went into some topics in depth-especially in chapters nine and thirteen-introducing vocabulary and concepts found in the philosophical texts studied in the great monastic universities. These terms and concepts may not be familiar to the general reader, and it may require a stretch of the mind to understand their subtleties. It would have been easy to remove these topics from the manuscript, resulting in easier reading in some sections. However, I think this would have been a great loss. Where else could the average reader receive these explanations? How else could we be challenged to go deeper? My own experience in studying the Buddha's teachings is that I need to be exposed to certain topics repeatedly, knowing that I will not understand them the first few times. However, through familiarity everything becomes easier. If I constantly avoid the difficult subjects, then my practice will remain superficial. So I am happy to "plant seeds" in my mind by repeatedly hearing these topics, knowing that by making some effort, understanding will gradually come. The great masters have said that as we purify our negativities, and accumulate positive potential, we will be able to understand things that were previously obscure to us.

In chapter eleven, Geshe-la went into detail when describing the taking and giving meditation. I have heard teachings on this many times before, but find his explanation here especially captivating and stimulating. Just reading the material created a sense of joy in my mind, so when editing, I decided to include all the details in the hopes that the reader would benefit from this precious teaching.

However, if a particular explanation is too detailed or too complex for your needs, please feel free to go on to the next section. Each person's needs and ways of learning and practicing are unique and need to be respected.

As in most explanations of the Bodhisattvas' practices, the ideal is presented. Often we in the West feel that we should be able to understand and practice everything immediately. However, learning the Dharma is different from learning secular subjects, and we are not expected to be able to put everything into practice at once. Rather, we practice according to our present needs and abilities. That enables us to progress gradually, so that later we will have the ability to do practices that initially were too difficult for us. Even though some practices may seem too advanced for us now, we can still appreciate and respect those who are able to engage in them and know that one day we, too, will be find these practices within our range.

The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas is found at the end of this volume, and an outline of the text is included as an appendix. This outline gives an overview of the text and shows how the various topics fit together. The glossary contains the general meanings of Dharma terms found in this book. Please note that these are not translations of the definitions found in philosophical texts. The section on recommended reading lists resources that complement the teachings in this book.

A few comments about language usage are needed. In an attempt to be gender inclusive, "he" and "she" have been alternately used in situations that, in fact, include people of both genders. The term "our mind" does not mean that we share one mind. We each have our own mindstream. It simply means "one's mind" or "your mind."

Geshe Tegchok taught The Thirty-seven Practices in Tibetan, and Thubten Sherab Sherpa did the oral translation. This was checked and retranslated when necessary by Ven. Steve Carlier. In preparing this book, I also drew on the teachings Geshe Tegchok gave on Mind Training Like Rays of the Sun by Namkha Pel, which were translated by Ven. Steve Carlier, and included them in appropriate areas in this book. This serves to depict the Bodhisattvas' practices more completely. The translation of the root text was done by Ruth Sonam and excerpted with permission from The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas by Geshe Sonam Rinchen, translated and edited by Ruth Sonam (Ithaca NY: Snow Lion Publications, 1997). I would like to thank Ven. Steve Carlier for making final corrections on the content, Dan Black for his editorial suggestions and for proofreading the manuscript, and Peter Green for doing the illustrations. All errors are my own. Many thanks also to the monks of Nalanda Monastery for making these teachings possible and to the members of Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle who supported me while I edited this book. May this book contribute towards alleviating the suffering of sentient beings and enabling them to discover and develop their good qualities and joy.

Next page