Buenos Aires: The Biography of a City

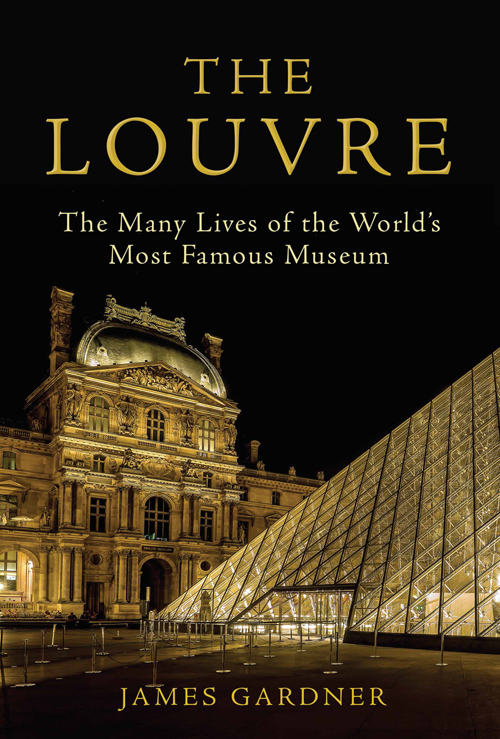

THE

LOUVRE

The Many Lives of the Worlds Most Famous Museum

JAMES GARDNER

Copyright 2020 by James Gardner

Cover design by Gretchen Mergenthaler

Cover photograph Leslie Wilk/Alamy

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

FIRST EDITION

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in Canada

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: May 2020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-4877-3

eISBN 978-0-8021-4879-7

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

20 21 22 23 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother,

Natalie Jaglom Gardner

29 September 192422 February 2019

In telling the story of the Louvre, I have proceeded simultaneously along three fronts, the architectural, the institutional and the historical. That is to say that the present book describes the evolution of the building known as the Louvre from its earliest foundations as a medieval fortress to the completion of I. M. Peis glass pyramid eight centuries later. But the book also considers the institutional genesis of the great museum that has now inhabited that structure for over two hundred years, animating it as a soul animates a body. Finally, and no less essentially, the book explores the crucial role that the Louvre has played in the history of France and its ruling dynasties, from the time of the Third Crusade, through the Revolution, to the Second World War and beyond.

Although this tale is well worth telling, it is also one of nearly incalculable complexity. Architectural history is to art history as three-dimensional chess is to the standard version of the game. In general, a painting or sculpture is created by one artist in a fairly abbreviated span of time and it remains in that final condition, shielded from the elements, for as long as its material foundations hold up. But a building, especially a great building, is often a labor of centuries, engaging the talents of generations of architects and codifying in stone the often discordant whims of several great dynastic families. It is subject to constant attack from the elements, and not infrequently from the fusillades of invading armies and the vicissitudes of siege warfare.

Perhaps no single structure on the planet exhibits this complex and protracted genesis as well as the Louvre, which, for more than eight hundred years, has been in a process of becoming. What we see todaynot counting what has been destroyed beyond recallis the result of some twenty discrete building campaigns over five hundred years, and indeed, the buildings history goes back three and a half centuries before the construction of the earliest structures that are now visible above ground.

But traditionally architects and their patrons seek to belie such troubled gestation and to persuade visitors that they stand before a serenely unified project born of a single building campaign. And that is how most visitors see the Louvre, and how, for a long time, I too saw this incomparable palace. I was aware that there were stylistic disparities among its parts and that it had emerged over a period of centuries. But one day, as I was entering the grounds of the Louvre for perhaps the hundredth time, it suddenly came home to me that I knew almost nothing of the story behind what I was seeing. As I began to look into the matter, my initial curiosity grew upon itself, resulting in the book that you now hold in your hands.

In several respects this book is antithetical to the one I wrote immediately before it, a history of the city of Buenos Aires. That book engaged a massive subjectan entire citythat had been relatively little studied and, to the extent to which it had been studied at all, in a rather unsystematic, even shoddy way. By contrast, the focus of the present book is a single objectalthough, admittedly, one of the largest on earthevery square inch of which has been scrutinized by the most eminent and exacting art and architectural historians, not only in France, but throughout the world. My skills and training being those of a cultural critic rather than a researcher in recondite fields, I freely admit that I have left archival inquiries to the many scholars who are far more practiced and proficient in such pursuits. I am also delighted to acknowledge my debt to the three-volume Histoire du Louvre, edited by Genevive Bresc-Bautier and Guillaume Fonkenell, which appeared at precisely the moment when I began writing my book. Engaging the talents of nearly a hundred scholars and extending to nearly two million words, that book is a summa of archival researchintended mainly for scholars in the fieldinto every imaginable aspect of the history of the Louvre as a building and an institution.

In the interests of housekeeping, the reader will allow me to make several somewhat disconnected points. The first is that, for the sake of consistency, I have numbered the floors in the Louvre, and elsewhere, after the European fashion, rather than the American: the lowest externally visible part of a building is its ground floor, followed by the first floor (which in the United States is called the second floor). The Louvre thus has three levels (not counting several levels below grade): the ground floor, the first floor and the second floor.

Next, it should be stated that the entire western side of the Louvreas it opens outward to the Champs-lyses and the Arc de Triomphewas once occupied by a great palace, Les Tuileries, that was integral, and physically connected, to that architectural complex that we call the Louvre. This palace burned to the ground under the Communards in 1871. Of necessity, I refer to it frequently in the course of the present narrative, but far less for its own sake than for its influence on the evolution of the Louvre as we know it today.

A book of this sort necessarily mentions a great number of paintings, sculptures and architectural elements, more than could be conveniently included among the illustrations. But if this book has a generous complement of images, it has been written in the full awareness of the new realities of the internet: an illustration of every work of art mentioned in the book can be found with relative ease online, and in a higher, crisper resolution than any printed book could achieve. The reader is therefore encourged to seek these images at that bountiful source.