KIDNAPPED BY THE VATICAN?

VITTORIO MESSORI

KIDNAPPED BY THE

VATICAN?

The Unpublished Memoirs

of Edgardo Mortara

Translated by Michael J. Miller

Foreword by Roy Schoeman

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Original Italian edition:

Io, il bambino ebreo rapito da Pio IX:

Il Memoriale inedito del protagonista del caso Mortara

2005 by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Milan, Italy

2015 by Mondadori Libri, Milan, Italy

The memoirs of Father Edgardo Mortara were originally written in Spanish but were never published. An Italian translation of them by Andrea Vannicelli, which was approved by the author, is the basis of the English translation in this volume.

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from Revised Standard Version of the BibleSecond Catholic Edition (Ignatius Edition) copyright 2006 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Cover photograph of Edgardo Mortara

Courtesy of Archivio dei Canonici Regolari Lateranensi

Cover design by Enrique Javier Aguilar Pinto

2017 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-198-8 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-779-2 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2017938952

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

The Autobiographical Account of the Mortara Case Written by the Protagonist, Reverend Father Pio Maria Mortara, C.R.L.

FOREWORD

Why was the Mortara case such a cause clbre in the second half of the nineteenth century, and why did it remain so controversial that it was the primary objection to the recent beatification of Pope Pius IX, almost a century and a half later? The case sits at the crossroads of the greatest social transformation of modern times: from a fundamentally religious view of the world to a fundamentally materialistic one. Those two views can lead to diametrically opposed conclusions about the Mortara case.

Promoting the welfare of its citizens has always been seen as a legitimate concern of the state, perhaps the primary one. Throughout the United States and Europe today, the state is considered to have the right even to remove a child from his parents to protect the childs physical and emotional well-being; this has been done in situations in which the child was deprived of proper medical care, left unattended in a parked car, allowed to play unwatched in a public park, or even subjected to secondhand smoke. Although people differ on the merits of particular cases, by and large we accept the principle that at some point the welfare of the child justifies the states intervening and overriding the parents right to care for the childbut only temporal, not eternal, welfare is usually considered.

But what if the teaching of the Catholic Church is true? What if, once created, the human person lives for all eternity, and the nature of that eternitywhether perfect bliss or unending miseryis dependent on the sacraments and on the persons moral formation? Then should not the same principle that gives the state the right to intervene for the physical welfare of the child give the state the right, perhaps even the duty, to intervene for the eternal welfare of the child as well?

That is the issue at the heart of the Mortara controversy. The Mortara case occurred when the fundamental notion of the state was undergoing a transition away from that of the confessional stateone in which there is an official state religion and the rights of other religions, if tolerated at all, are restricted. Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, popes consistently defended the confessional state against the encroachment of an increasing separation of Church and State.

The Mortara case emerged not only at the height of this philosophical shift in the idea of the state but also amid the violent transformation of Italy from a number of independent states, including the Papal States under the popes direct rule, to a single unified state. Although the motivation of the Risorgimento was in part nationalistic, it was also heavily influenced by strongly anti-Catholic, anticlerical, antipapal forces.

In fact, much of the political reformation of Europe following the misnamed Enlightenment can be seen as a geopolitical manifestation of the rejection of Christianity, God, and religion that saw its first brutal expression in the homicidal, anti-Church French Revolution and continued in the atheistic communist revolutions that have plagued the world since the start of the twentieth century. Many of the conflicts in twentieth-century Europe can be better understood in terms of atheisms battle against the Church than in terms of competing ethnic or national interests. The rise of fascism in Europe is directly linked to this battle, for the major figures associated with fascism in EuropeFranco, Mussolini, and Hitlerin their ascents to power, all presented themselves as defenders of the Christian state against atheistic communism.

The Mortara case arose in the center of this perfect storm of social and political turmoil. In addition to the Risorgimento in Italy, revolts against the confessional state were occurring or were soon to occur throughout Europe, as the shackles of Christendom were thrown off in favor of materialistic secularism in France, England, Spain, and Germanyand, of course, in Holy Mother Russia.

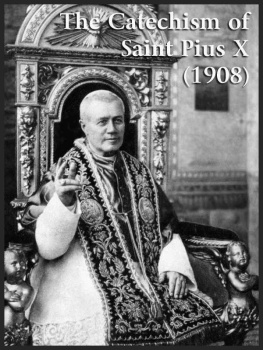

Into that battle waded, unknowingly, an innocent six-year-old boy, a Catholic nursemaid, and a pope of uncompromising integrity and courage. The result was the Mortara affair. Pope Pius IX stood as a bulwark against this secularizing trend that was transforming Italy and all Europe. The Mortara case provided an ideal opportunity for his opponents to attack him personally, as well as the authority of the Church and the very idea of a confessional state. For ones view of the morality of his actions depends on ones acceptance, or rejection, of the truths of the Catholic faith. In the light of the faith, what the pope did can be seen as not only legally justified but also morally justified; in the darkness of a total rejection of the faith, it appears unconscionable.

The circumstances of the case are straightforward. At the time of the incident, the Mortara family resided in Bologna, within the Papal States that were under the rule of Pope Pius IX. Contrary to the law at the time, the Jewish family employed a Catholic nursemaid, who surreptitiously baptized the infant Edgardo when he was at the point of death. The infant unexpectedly recovered; later, when the circumstances became known, the Mortara family was informed that since Edgardo was now a baptized Catholic, they would have to give him a Catholic education, as the law in the Papal States required for all Catholic children. Pressured by anticlerical forces, the parents steadfastly refused, requiring the pope to remove the child from his family in order to provide that Catholic education.

If one rejects the objective truth of the Catholic faith, then the Catholic confessional state, represented by Pope Pius IX as ruler of the Papal States, had no right to impose its beliefs and remove a surreptitiously baptized child from the care of his Jewish parents in order to assure him a Christian education. If, however, one accepts the teachings of the Church about the effects of the sacraments and the conditions for eternal salvation, might one not conclude that the pope had not only the right, but also the duty, to do as he did? Should the pope have put greater weight on the considerations in favor of the parents, or on the eternal salvation of the Christian childs soul? Whichever decision he made, one day he would have to answer for it before God.

Coming as it did at the very end of the existence of the Papal States and at the time of the emergence of increasingly successful anti-Catholic and anticlerical forces trying to remove all trace of Christ from Christendom and of Holy Roman from Holy Roman Empire, the case drew down upon itself all of the passion and fury of that conflict. In the words of Pius IX, All the governments of the Old and the New World united and conspired to take away from me, from Christ, and from His Church, the soul of this child.... I do not feel sorry, though, for what I have done on his behalf, to save a soul that cost the blood of God. On the contrary, I ratify and confirm everything. And what was Edgardos view of the popes decision? In his memoirs, he wrote The angelic, admirable, immortal Pontiff... was far above the frothing, angry waves of the human passions that conspired with Hell to wage a war without quarter against the Church of Christ.... He was as great as his magnanimous heart, as fearless and invincible as the Lion of Judah.

Next page