DAVID I. KERTZER

The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara

David I. Kertzer was born in 1948 in New York City. The recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1986, he has twice been awarded, in 1985 and 1990, the Marraro Prize from the Society for Italian Historical Studies for the best work on Italian history. He is currently Paul Dupee, Jr., University Professor of Social Science and a professor of anthropology and history at Brown University. He and his family live in Providence.

ALSO BY DAVID I. KERTZER

Politics and Symbols:

The Italian Communist Party

and the Fall of Communism

Sacrificed for Honor:

Italian Infant Abandonment

and the Politics of Reproductive Control

Ritual, Politics, and Power

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, JULY 1998

Copyright 1997 by David I. Kertzer

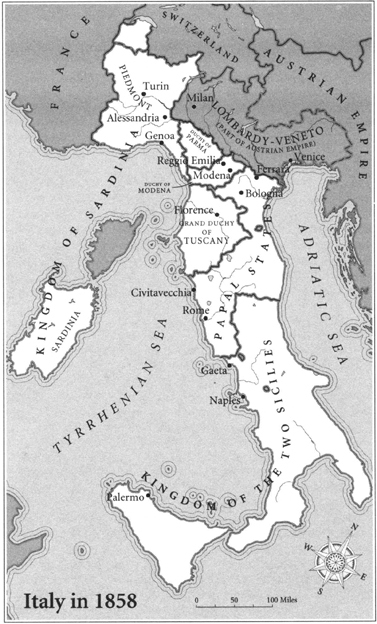

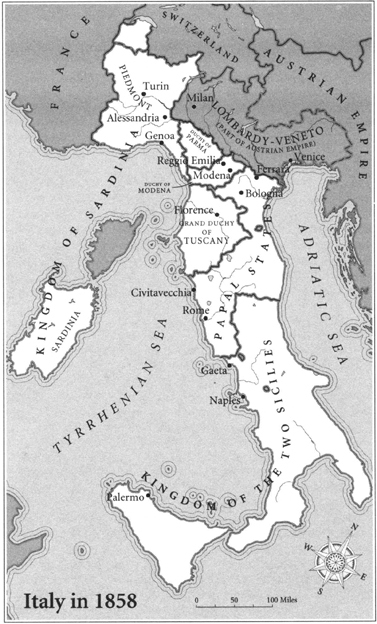

Maps copyright 1997 by David Lindroth, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1997.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Kertzer, David I.

The kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara / by David I. Kertzer.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Mortara, Pio, d. 1940. 2. JewsItalyBolognaConversion to ChristianityHistory19th century. 3. Converts from JudaismItalyBolognaBiography.

I. Title.

DS135.I9M595 1997

945.004924dc21 96-39159

eISBN: 978-0-307-48671-4

Random House Web address: www.randomhouse.com

v3.1_r2

To my father, Morris Norman Kertzer,

and to my daughter, Molly Emilia Kertzer,

with love and appreciation

CONTENTS

Maps will be found opposite the title page

and on

PROLOGUE

I T WAS the end of an era. Regimes that had lasted for centuries were about to be swept away. On the Italian peninsula, the old world of papal power and traditional authority uneasily faced the disparate progeny of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the champions of modern industry, science, and commerce. The proud warriors of the old and the new viewed each other warily, in mutual incomprehension. Each side waved its own flags, intoned its own verities, worshipped its own icons, sang praises to its heroes, and heaped scorn on its enemies. Revolutionaries dreamed of utopic futures, far different from the oppressive present; liberals envisioned a new political order, based on constitutional rule; and even conservatives began to wonder whether the old order could stand much longer. New gods were being born, new objects of adulation. In Italy, out of the patchwork of duchies, grand duchy, Bourbon and Savoyard kingdoms, Austrian outposts, and the pontifical state itself, a new nation-state was soon to take shape whose boundaries were as yet unknown and whose nature was as yet unimagined. Subjects would soon become citizens. Yet for the mass of illiterate peasants, nothing much would seem to change.

Nowhere in the West was the chasm between the old world and the new so wide as in the lands of the pope-king. Where else, indeed, could rule by divine right be so well entrenched, so well justified ideologically, so spectacularly elaborated ritually? The Pope had been a worldly prince, a ruler of his subjects, for many centuries, and the contours of his domain in 1858stretching from Rome in a crescent sweeping northeastward around the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and up to the second city of the Papal States, Bologna, in the northwere much the same as they had been three and a half centuries before. The Pope ruled his state because that was what God willed. The revolutionary notions that people should choose their own rulers, that they should be free to think what it pleased them to think, believe what they chose to believethese were not simply wrongheaded but heretical, the devils work, the excrescences of Freemasons and other enemies of God and religion. The world was as God had ordained it. Progress was heresy.

But while the pontifical state still stood in 1858, it had not survived the previous seven decades unbattered. When French soldiers streamed down the Italian peninsula in 179697, the Papal States were gobbled up; in the years that followed, two popes were driven from Rome into humiliating exile, and Church property was auctioned off to the highest bidder, swelling Napoleons coffers. Although with Napoleons collapse Pope Pius VII returned to the Holy City in 1814 and the Papal States were restored, what had once appeared so solida product of the divine order of thingsnow seemed terribly fragile. Conspiracies against the Popes worldly rule sprouted; revolts broke out. At midcentury another pope was forced to flee Rome, this time fearful of murderous mobs, and had to rely on foreign armies to restore his rule and then protect him from his own mutinous subjects.

Among those subjectsthough, for the most part, far from mutinouswere the Jews, the Popes Jews. Having lived in Italy since before there were any Christians, they nonetheless could not shake off their status as outsiders, petitioners for the privilege of being allowed to remain where they were. Few in numberfewer than fifteen thousand in all the Papal Statesthey were high in the clergys consciousness, occupying a central, if unenviable, position in Catholic theology: they were the killers of Christ, whose continued wretched existence served as a valuable reminder to the faithful, but who would one day see the light and become part of the true religion, helping to hasten the Redeemers return. Since the sixteenth century, the popes had confined them to ghettoes to limit the contagion. No Christian was allowed in their homes; theirs was a society apart. Still, life in the ghetto had its joys and consolations. There the Jews had a rich communal life, their own institutions, their own synagogues, rabbis, and leaders, their own quarrels and triumphs, their own divinely ordained rites that structured each day of their lives and each season of the year.