Copyright 2008 by David I. Kertzer

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Kertzer, David I., date.

Amalias tale : an impoverished peasant woman, an ambitious attorney, and a fight for justice / David I. Kertzer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-618-55106-4

ISBN -10: 0-618-55106-9

1. Bagnacavalli, AmaliaTrials, litigation, etc.History. 2. Bologna (Italy)Trials, litigation, etc.History. 3. Trials (Malpractice)ItalyBolognaHistory. 4. Barbieri, Augusto. 5. Medical personnelMalpracticeItalyBolognaHistory. 6. Medical laws and legislationItalyCriminal provisions. 7. Negligence, CriminalItaly. 8. LawyersItalyBolognaHistory. 9. Syphilis. I. Title.

KKH 41. B 65 K 47 2008 344.454104121dc22 2007008519

e ISBN : 978-0-547-34490-4

v3.1115

FOR TWO JACKS

Little Jacob Bear and his sorely missed

great-grandfather, Jacob Dana

Prologue

T HE STORY I am about to tell may seem strange, even bizarre. No one who reads this book will have ever heard of its protagonist, an illiterate young peasant woman, much less of the seemingly hopeless battle she fought, taking on a count and assorted others of her social superiors. Nor is the reader likely to have ever heard of the nature of her complaint, of the nineteenth-century scourgewhose name was so terrible that it was rarely utteredthat was devastating remote villages in Italy, France, and beyond.

But I offer this unknown story, not because of its ability to shock, but because it offers a rare glimpse into a world that is no more. From its idiosyncratic vantage point, it allows us to peer deep into a world in transformation, a society changing with breathtaking speed.

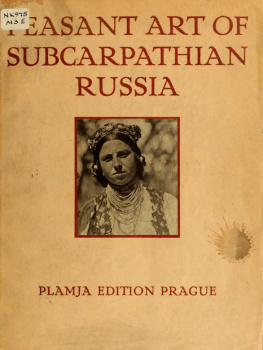

Italy in the not so distant past was a country of huge contrasts, of nobles and peasants, of great writers and a mass of illiterates, of fabulous palaces and rat-infested hovels. Until recently, most Italians lived in poverty in the countryside while the rich and powerful lived in the cities. Civilizationcivilt in Italianmeant urban life. Life in the countryside was regarded as fine for the contadini, the peasants, but only because no one thought of them as part of civilized society. There was no romance to rural living in Italy, no glorification of the soil or those who tilled it. Yet the worlds of rich and poor, of city and countryside, were intimately linked. Vast areas of fertile farmland were owned by the urban elite, who visited each fall to be sure that the peasants who farmed it did not hold anything back. The parish priests who tended their rural flocks were, in this respect, no different, for they too took their orders from their superiors in the city.

The old social order began to change after the explosion that was the Risorgimento. Indeed, Italy only came into existence as a unified country in 1861, and even then Rome and the region around it remained a holdout. It was only in 1870, when the Italian army literally blasted through the medieval wall surrounding the Eternal City, that Rome fell and the defeated pope, Pius IX, retreated to his Vatican palaces as a self-styled prisoner. The following year Rome became the capital of the new Italian state.

At first, not much changed in the lives of most Italians: the peasants continued to till the soil and tend their flocks in much the same way their ancestors had. True, there was now a parliament and no longer an absolute ruler. But the senators were appointed by the king, and although the members of the House of Deputies were elected, no peasant could cast a ballot. In fact, in the years after unification, the majority of Italians, the contadini, had scant interest in their new government other than to lament it as another source of taxes, military conscription, and support for the landlords. Few of them could read government proclamationsor anything elsenor could they understand what either their king or those in parliament said, for such speech was unintelligible to the dialect-speaking peasantry.

While at first it seemed that, to paraphrase the aristocratic protagonist of The Leopard, all had to change so that all could stay the same, it soon became clear that change was coming. Long-held assumptions were being questioned, not least among them the notion that the masses of people had no rights, that it was up to the privileged few to decide what was best for those beneath them.

In 1876, the historic rightclosely tied to the aristocracy and committed to maintaining the old social hierarchyfell, and the left gained control of the Italian parliament. Although far from a revolutionary force, and soon to show itself all too ready to compromise to hold on to power, the left began a series of reforms that would transform the Italian countryside. Not the least of these was the spread of mandatory schooling in the hinterland and, by the turn of the century, the first, albeit weak, rules regulating womens and child labor.

Yet the major pressure for change in those years came not from the government but from quite another source. Ever since the revolutions of 1848, European society had been roiled by a maelstrom of popular movements against the privileged classes. With the First and then the Second International, these protests mutated from a disorganized series of abortive anarchist uprisings and associated millenarian delusions into a rapidly expanding and increasingly powerful socialist movement. In northern Italy in the last two decades of the century, tens of thousands of workers and peasants formed local cooperatives and leagues, demanding a transformation of society. When they began to coalesce into a nationwide socialist party in the 1890s, the elites began to get nervous. The peasants, who had for centuries seen themselves destined to spend their lives toiling for their wealthy landowners, began to question their fate. Rural strikes spread and outrageousor so they seemed to the padroninew demands were made.

The tale of Amalia Bagnacavalli is the story of people living amid this historic upheaval. Her story can scarcely be imagined any earlier in Italian history. It would have been inconceivable that an illiterate peasant woman could take legal action against one of Bolognas foremost aristocrats and one of the major urban institutions of her timethe Bologna foundling home. For all this to take place, a host of major changes had to appear. There had to be an established legal system that would allow such a suit to be filed and pursued. There would have to be a crusading lawyer who, motivated by a new ideology and by social ambitions unleashed by the loosening of aristocratic control, would champion her cause. And there would have to be a change in legal philosophy in the courts, with lowly workers seen as having certain basic rights.

The settingthe foundling home and the vast network of babies and wet nurses spread throughout the hinterland it oversawmay seem to be an unlikely one for a story of dizzying social change. On the face of it the system, established centuries earlier, remained remarkably stable. Yet as a backdrop it offers some special advantages. In an Italy then poised between two epochs, nothing more dramatically illustrates the human dimensions of the relations of city to country, of rich to poor, than the foundling homes. For centuries they had taken in hundreds of thousands of babies abandoned by their parents at birth. In the days before safe artificial feeding, the survival of this mass of unfortunates depended on a peculiar system that involved renting out the bodies of peasant women. For these women in the desperately poor communities of the rural periphery, survival depended on being able to take in babies from the citys foundling home and getting paid for lending the infants their breasts. The cities sent thousands and thousands of these unfortunate creatures, as they were called, into the countryside, pumping large amounts of money into the rural communities along with them. In the poorest villages in the late nineteenth century, thousands of women took in such children, like their mothers and grandmothers before them.

Next page