ALSO BY SAUL FRIEDLNDER

When Memory Comes: The Later Years

Franz Kafka: The Poet of Shame and Guilt

Nazi Germany and the Jews, 19331945 (Abridged Edition)

The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 19391945

Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution, 19331939

Memory, History, and the Extermination of the Jews of Europe

Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the Final Solution (editor)

Visions of Apocalypse: End or Rebirth? (co-editor)

Copyright 1978 by ditions du Seuil, Paris, France

Originally published in French as Quand vient le souvenir ,

Translation copyright 1979 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC

All rights reserved.

Published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC

Introduction copyright 2016 by Claire Messud

Production editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 FifthAvenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Friedlnder, Saul, 1932- author. | Lane, Helen R., translator.

Title: When memory comes / by Saul Friedlnder; translated from the French by Helen R. Lane; with an introduction by Claire Messud.

Other titles: Quand vient le souvenir . English

Description: New York : Other Press, [2016] | ?1979 | Originally published: 1st ed. New York : Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1979.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016003710 (print) | LCCN 2016005051 (ebook) | ISBN 9781590518076 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781590518083 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Friedlnder, Saul, 1932- | JewsFranceBiography.

| Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)FrancePersonal narratives. | FranceBiography.

Classification: LCC DS135.F9 F74513 2016 (print) | LCC DS135.F9 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/18092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016003710

eBook ISBN: 978-1-59051-808-3

v3.1

For Eli, David, and Michal,

and for Hagith,

who has always understood

When knowledge comes, memory comes too, little by little. Knowledge and memory are one and the same thing.

Gustav Meyrink

Contents

INTRODUCTION

by Claire Messud

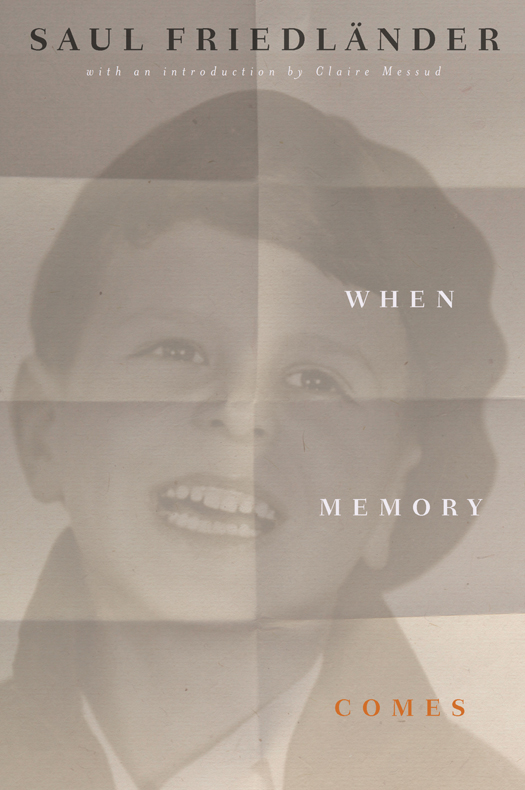

We have understood, at least since Aeschylus, that wisdom is attained through suffering. But it is a truth powerfully reinforced by the experiences of Saul Friedlnders generation: born into a prosperous, assimilated Jewish family in Prague in 1932, Friedlnder had experienced by the age of sixteen more trauma, upheaval, and grief than many do in a lifetime. This memoir of his youth, written in a moment of comparative hope (at the time of Anwar Sadats visit to Israel in 1977, in the run-up to the Camp David Accords of 1978), is valuable not simply for Friedlnders inspiringly vivid and elegant account of his youthful travails, but also for his Tiresian clarity of vision, and for the forthrightness of his narrative. It is, if anything, only more relevant forty years after its initial publication.

Few have inhabited such diverse personae as did the young Friedlnder: born Pavel, a Czech boy, he became Paul when his family fled to France in 1939, settling in Nris les Bains, Vichy on a smaller scale minus the government plus the Jews. Subsequently, placed in a Jesuit boarding school, Saint-Branger, by his parents (who would themselves die in Auschwitz), he was known as Paul-Henri Ferland. Immediately after the war, having come to understand for the first time his Jewish identity, he was sent to a Russian-Jewish guardian in Paris, where he attended the Lyce Henri IV. From there, in the spring of 1948, he ran away to join Betar, a youth movement with ties to Menachem Begins Irgun. As a new Israeli, he took the Hebrew name Shaul, the French transliteration of which is Saul.

Internal confusion was inevitable along his journey, as was a sense of isolation. As a teenager, he refused meat at his first Passover Seder because it was Good Friday. Of his Catholic years at Saint-Branger, he recalls that, unaware of his Jewishness, I soon felt a vocation: I wanted to become a priest; I liked the austere simplicity, the intense devotion of the early mass at which I sometimes served. He remembers, too, being part of the schools majority, faithful to the Marshal [Ptain] in every way, that ostracized a young boy named Jean-Marc on account of his Gaullist views: how happy I was to be able to share this fraternal warmth and look upon this proscribed youngster with scornful eyes! Even in midlife, he acknowledges that I still feel a strange attraction, mingled with a profound repulsion, for this phase of my childhood.

From this unlikely extreme, with the revelation of his heritage and of his parents fates, he turned, in 19471948, to fervent Zionism. As he abandoned his French schooling and his known world, he did so for reasons not wholly dissimilar to those behind his earlier enthusiastic embrace of Catholicism: I was all alone in the world To leave for Eretz [Israel] meant merging my personal fate with a common lot, and also a dream of communion and community. Ultimately, an unmitigated sense of belonging would continue to elude Friedlnder as an adult, and it is this very not-belonging that affords him so rare and crucial a perspective.

He recalls a moment when, as a newly Jewish-identified teenager, he sought to conjure imaginatively an experience of the camps Belzec and Maidanek (which of course he had not seen):

It was only much later that I understood that what was missing was not literary talent but rather a certain ability to identify. The veil between events and me had not been rent. I had lived on the edges of catastrophe; a distanceimpassable, perhapsseparated me from those who had been directly caught up in the tide of events, and despite all my efforts, I remained, in my own eyes, not so much a victim asa spectator. I was destined, therefore, to wander among several worlds, knowing them, understanding thembetter, perhaps, than many othersbut nonetheless incapable of feeling an identification without any reticence, incapable of seeing, understanding, and belonging in a single, immediate, total movement. Henceneed I say?my enormous difficulty in writing this book.

Seeking in part to rend the veil, in part to understand his pasthaving fruitlessly attempted a Proustian conjuring with a strawberry milkshake in the Paris milk bar hed frequented with his mother as a small boy: though it brings back memories, [it] doesnt summon up what I am looking for No, really not Friedlnder turned, with ardor, to history. The memoirs title is the inversion of a quotation from Gustav Meyrink (author of The Golem, an Austrian writer and Prague resident who died in the year of Friedlnders birth): Meyrink wrote that When knowledge comes, memory comes too; for Friedlnder, in lifes path of self-discovery, when memory comes, knowledge comes too.

The essential and abiding lesson is that Knowledge and memory are one and the same thing. To bear witness to his multiple, incongruent selves amounts, for Friedlnder, to acknowledging the experiences of others, whether they are fellow Jews or Palestinians or his Czech nanny Vlasta, who went on to work for the family of a German general. He has had the fortitude to examine clearly even the acts of the Nazis themselves. To bear witness is to recognize, in his young daughters face, the echo of his lost mothers; or simply to evoke, with magnificent Tolstoyan precision, the details of a distant memory: