Table of Contents

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Support for this book was generously provided through fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the American Council of Learned Societies.

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54371-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fulton Brown, Rachel, author.

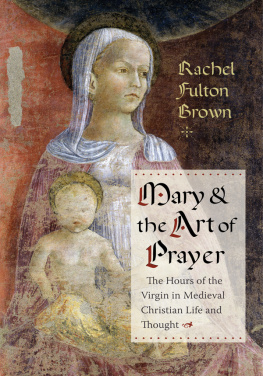

Title: Mary and the art of prayer : the hours of the Virgin in medieval Christian life and thought / Rachel Fulton Brown.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017009362 (print) | LCCN 2017034281 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231543712 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231181686 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Catholic Church. Little office of the Blessed Virgin Mary. | Mary, Blessed Virgin, SaintPrayers and devotions. | Mary, Blessed Virgin, SaintDevotion to. | Spiritual lifeChristianityHistory.

Classification: LCC BX2025 (ebook) | LCC BX2025 .F85 2017 (print) | DDC 264/.020150902dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009362

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover image: Mondadori Portfolio/Electa/

Paolo e Federico Manusardi/Bridgeman Images

For my mother, the strongest woman in my life, and in memory of my father, who sent me on the quest.

R hetorically, prayer may take many forms. In acknowledgments, it takes the form of thanksgiving.

I am grateful to Mary, for choosing me to write this book on her behalf and trusting me, a cradle Presbyterian, with the recovery of the devotion with which medieval Christians prayed to her.

I am grateful to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for giving me a year (2004) as a New Directions Fellow to study cognitive and biological psychology, that I might develop the tools that I needed to get inside the medieval practice of prayer.

I am grateful to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the American Council of Learned Societies for fellowships to spend two years (20082009, 20122013) to concentrate on writing this book. Thanks to their generosity, funds were likewise available to bring this book to press. Thanks also to the University of Chicago where I teach for leave during this time.

I am grateful to Christopher Fletcher for serving as my research assistant for two years, for photocopies and rich conversation whenever he brought materials to me.

I am grateful to Google Books, Hathi Trust, and the staff of the Joseph Regenstein Library for making it possible to do much of the work for the latter part of this book from my couch. I am particularly grateful to David K. Larsen for setting up the Scan & Deliver service at the library so as to make its collection more accessible to those of us working from home.

I am grateful to the British Library and the Regenstein Library Department of Special Collections for access to the Books of Hours in their care, and to Wellesley College Library, Special Collections, for access to their beautiful manuscript of Richard of Saint-Laurents De laudibus beatae Mariae virginis.

I am grateful to the late Erik Drigsdahl for maintaining his magnificent site on Books of Hours and for advice on the books that he knew.

I am grateful to the students in my courses on Mary and Mariology (spring 2012, autumn 2015), The Psalms in Medieval Christianity (autumnwinter 20142015), Medieval Biblical Exegesis (autumnwinter 20112012), Praying by the Book (spring 2007), and Spiritual Exercises: History and Practice (spring 2006) for helping me read the texts on which much of this book is based, and to my students in Tolkien: Medieval and Modern (spring 2005, 2008, 2011, 2014) for being willing to subcreate with me.

I am grateful for the opportunities I had to present portions of this work in progress to the Medieval Studies Workshop at the University of Chicago, Brent House Episcopal Campus Ministry, the Medieval Intellectual History Seminar, St. Louis University, the University of California at Los Angeles, the University of California at Berkeley, the University of Mississippi, Marquette University, the University of Minnesota, DePaul University, Northwestern University, the University of Virginia, Villanova University, Yale University, the University of WisconsinMadison, the Medieval Academy of America, and the American Society of Church History.

I am grateful to Lynn Botelho, Caroline Walker Bynum, Steve Heyman, Nathaniel Goggin, Susan Melsky, Barbara Newman, Victor Pisman, and Jeffrey Stackert for conversation, scholarly advice, and constant encouragement, and to Barbara Friend Ish for helping me rewrite the opening meditation.

I am grateful to my three readers for the Press, particularly my devils advocate who made the argument against why my book should be published, and to my two angels for encouraging me to revise. I am more grateful than words can express to my editor Wendy Lochner for not giving up on my book throughout its lengthy review.

I am grateful to my mother for her generosity in helping me finish this book.

I am grateful to my husband Jonathan Brown for insisting even in my darkest moments that Mary wanted me to write this book, and to our son Rush for letting me drag him around all those churches in Belgium, for drawing the schema for the book, and for always being there when I needed a hug.

And I am grateful to my dog, for being my Joy. Every scholar needs a dog to get her outside for walks and to look at the trees.

Feast of St. Margaret of Scotland, A.D. 2016

Chicago, Illinois

In the ancient Hebrew tradition, the Divine Name or Tetragrammaton () was believed to be too sacred to speak out loud; accordingly, when reading from the scriptures, cantors would substitute the word Adonai, meaning Lord. When the scriptures were translated into ancient Greek, this spoken word was rendered (Lord). Translated into Latin, the Name as spoken became Dominus (Lord). In the King James Version of the scriptures published in 1611, the translators rendered the Name in capitals: Lord. According to medieval as well as ancient Christians, Jesus was not just a lord in the sense of a master or ruler; his proper name was (and is) Lord.