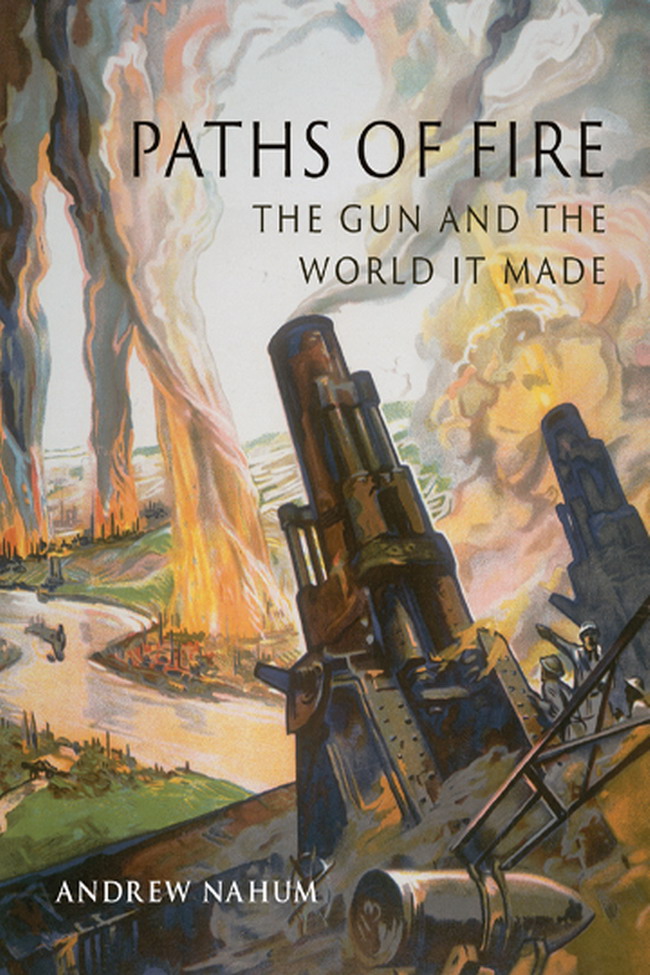

PATHS OF FIRE

PATHS OF FIRE

THE GUN AND THE

WORLD IT MADE

ANDREW NAHUM

REAKTION BOOKS

Published in association with

the Science Museum, London

TO FIONA, ADAM AND CHLOE

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

In association with the Science Museum

Exhibition Road

London SW7 2DD, UK

www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

First published 2021

Text SCMG Enterprises Ltd 2021

Science Museum SCMG Enterprises Ltd and logo design

SCMG Enterprises Ltd

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ Books Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789143980

CONTENTS

A 90 mm M1 anti-aircraft gun on display to the public at Watertown Arsenal, Massachusetts, c. 1950.

PREFACE

T ype Mikhail Kalashnikov into an Internet search engine like Google and the biography of the inventor comes back to you from secretive server sites in Oregon or Virginia in a blink, winging down optical fibres at the speed of light, or even along some old-style electrical phone cable, but still covering almost 200,000 km an hour (124,000 mph).

Squeeze the trigger of a Kalashnikov, and a bullet weighing about a quarter of an ounce is kicked up the barrel at a trivial fraction of that speed, propelled by a chemical bang that would have been quite familiar to Oliver Cromwell or General Custer. Modernity, in the everyday sense, is not evenly distributed. Ancient inventions, like the gun, are often still as prevalent, and as effective in their own domains, as those embodying the latest science.

Antique, yet contemporary, the gun dominates the world in obvious ways and is woven into the fabric of life, even though people in fortunate countries do not see them very often. But the influence of guns extends even beyond war, revolution and death, and this is not a conventional book about them. Nor is it about the gun lobby or the profound effects that firearms have on national affairs and on civil society.

Neither is it a synoptic history. There is no seamless arc, for example, from muskets to Kalashnikovs, or from the Renaissance cannon to the immense naval guns that could strike from 16 km (10 mi.) at Jutland although these things are all here.

Rather, this is a series of snapshots, showing how guns and gunnery have influenced our world and our culture in unsuspected, surprising ways. The flight of the cannon ball, for instance, helped overturn ancient theories of motion, inherited from the Greeks and clung to by the Catholic Church, for it was the study of ballistics, as well as the study of the heavens, that helped underpin the new science of Galileo and Newton. In spite of theology, here was an analysis that was seen to be genuinely useful by the most powerful actors in the emerging scientific world.

In the Second World War, predicting and calculating the aim of anti-aircraft batteries required the creation of small reactive on board computers, a development which points to a different history of computing and not the familiar one based on vast static mainframe machines. It is an alternative story because these new devices opened the path to artificial intelligence, to robotics, and even to the way in which we make sense of our own consciousness and powers of action today.

In another sphere, gun making refined the techniques and set the style for modern manufacture the systems that now produce so much stuff for us, so accurately and so cheaply.

Firearms and not just battles have also moulded political and international structures in intricate and surprising ways. Ronald Reagans Star Wars programme precipitated the end of the Cold War and also, perhaps, the end of the apparently impermeable Soviet empire. But at the heart of Reagans sally was an ultimately idealized gun Edward Tellers X-ray laser which existed only as a mythic weapon, an unrealized design that will, perhaps, never be made. Yet this promised ray gun proved to be an immensely effective lever during the years of the ReaganGorbachev diplomacy and provoked a seismic geopolitical shift. Its power was that it seemed to promise a nuclear umbrella, a robust new American defence against incoming missiles that would end the balance of nuclear terror.

It is a truism that arms development has an enormous and continuing effect on technological development and on social change. But the histories here show that this effect occurs not just in the familiar ways we know, but often by elliptical and surprising routes. The events here reflect these unexpected linkages. These are the less-considered tributaries of arms development, which also link to the broader, more generous and more surprising history of technology that has begun to emerge in recent years. These are episodes crammed with lesser known cross-connections, with individuals, and with contingencies that reveal an unsuspected undertow to the conventional and established tide of historical events.

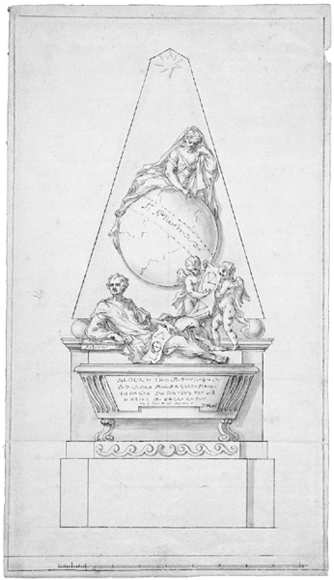

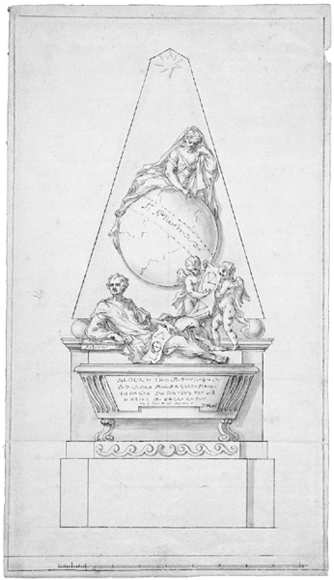

Newton as Olympian. The original 1731 design for Isaac Newtons memorial in Westminster Abbey by William Kent. For some reason Popes couplet was not used, and there is a much longer Latin inscription.

1

THE GEOMETRY OF WAR

I n 1931 a high-powered Soviet delegation attended the International Congress of the History of Science and Technology, held that year at the Science Museum in London. The members even arrived by aeroplane, then an emphatic statement of importance, and it has become a notable event for the history of science. It was, one historian commented, a Soviet road show since, instead of just the one speaker the conference expected, a small battalion (actually eight delegates) arrived, led by Nikolai Bukharin, once a close associate of Lenin. It was impossible to fit in papers from all the delegates but they were mollified by being given time for two papers and the publication of all the contributions at lightning speed an editorial marathon Five Day Plan based at the Soviet Embassy that resulted in the influential small volume Science at the Crossroads.

By far the most influential contribution to both the spoken session and the book, however, came from a comparatively little-known Soviet philosopher and physicist, Boris Hessen, with his paper The Social and Economic Roots of Newtons Principia, which located Newtons pure science firmly in the social milieu of its times and even in contemporary industrial and military events.

The paper, according to one reading, was written with an eye to saving [Hessens] career (and possibly his neck), since it was delivered in the presence of Ernst Kolman, arguably the most savage of Stalins intellectual cheerleaders, the delegate who had been assigned to the group by the Politburo and charged with reporting on the