Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Whos Black and Why?

A Hidden Chapter from the Eighteenth-Century Invention of Race

EDITED BY

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Andrew S. Curran

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England2022

Copyright 2022 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Andrew S. Curran

All rights reserved

Cover design by Ben Blount

978-0-674-24426-9 (cloth)

978-0-674-27612-3 (EPUB)

978-0-674-27613-0 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., editor. | Curran, Andrew S., editor.

Title: Whos black and why? : a hidden chapter from the eighteenth-century invention of race / edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Andrew S. Curran.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021036013

Subjects: LCSH: Acadmie royale des sciences (France) | Racism in anthropologyEuropeHistory18th century. | Scientific racismEuropeHistory18th century. | Black raceColorEuropeHistory18th century. | Black raceColorEuropePublic opinionHistory18th century. | EuropeansAttitudesHistory18th century. | RacismFranceBordeaux (Nouvelle-Aquitaine)

Classification: LCC GN27 .C38 2022 | DDC 305.8009409/033dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021036013

For Karen C. C. Dalton and Sheldon L. Cheek

CONTENTS

I promised you some returns for your favors, by sending you my Essay on that strange phenomenon in Nature, the cause of the colour of Negroes but I am afraid that this will come too late for a solution of the Prize-Problem proposed by the Academy of Bordeaux.

Letter from Dr. John Mitchell, of Urbana, Virginia, to Peter Collinson, Fellow of the Royal Society, London, April 12, 1743

I N 1739, the members of Bordeauxs Royal Academy of Sciences met to determine the subject of the 1741 prize competition. As was customarily the case, the topic they chose was constructed in the form of a question: What is the physical cause of the Negros color, the quality of [the Negros] hair, and the degeneration of both [Negro hair and skin])? According to the longer description of the contest that later appeared in the Journal des savants, the academys members were interested in receiving a winning essay that would solve the riddle of the African varietys distinctive physical traits. But what really preoccupied these men were three larger (and unspoken) questions. The first two were straightforward: Who is Black? And why? The third question was more far-reaching: What did being Black signify? Never before had the Bordeaux Academy, or any scientific academy for that matter, challenged Europes savants to explain the origins and, implicitly, the worth of a particular type of human being.

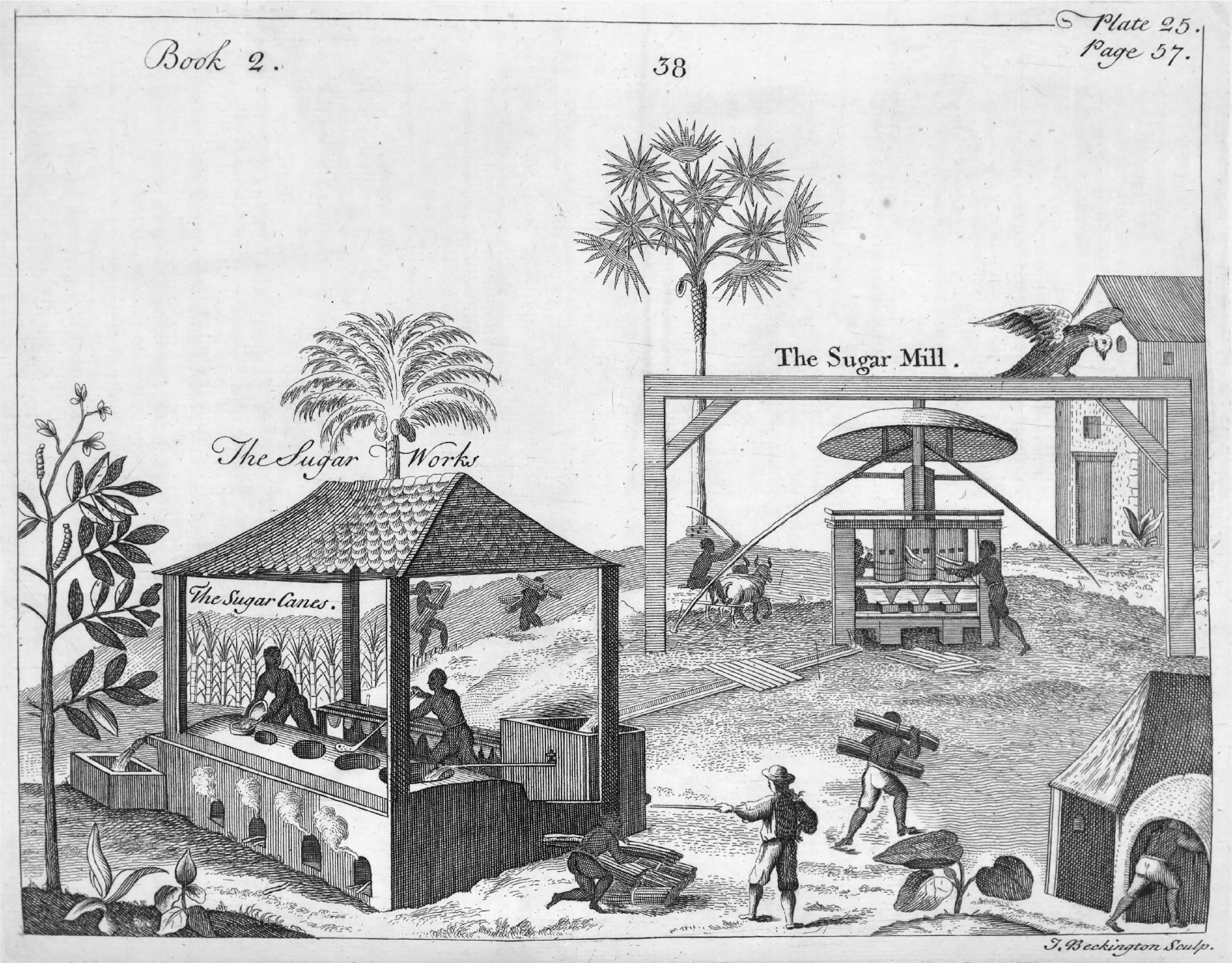

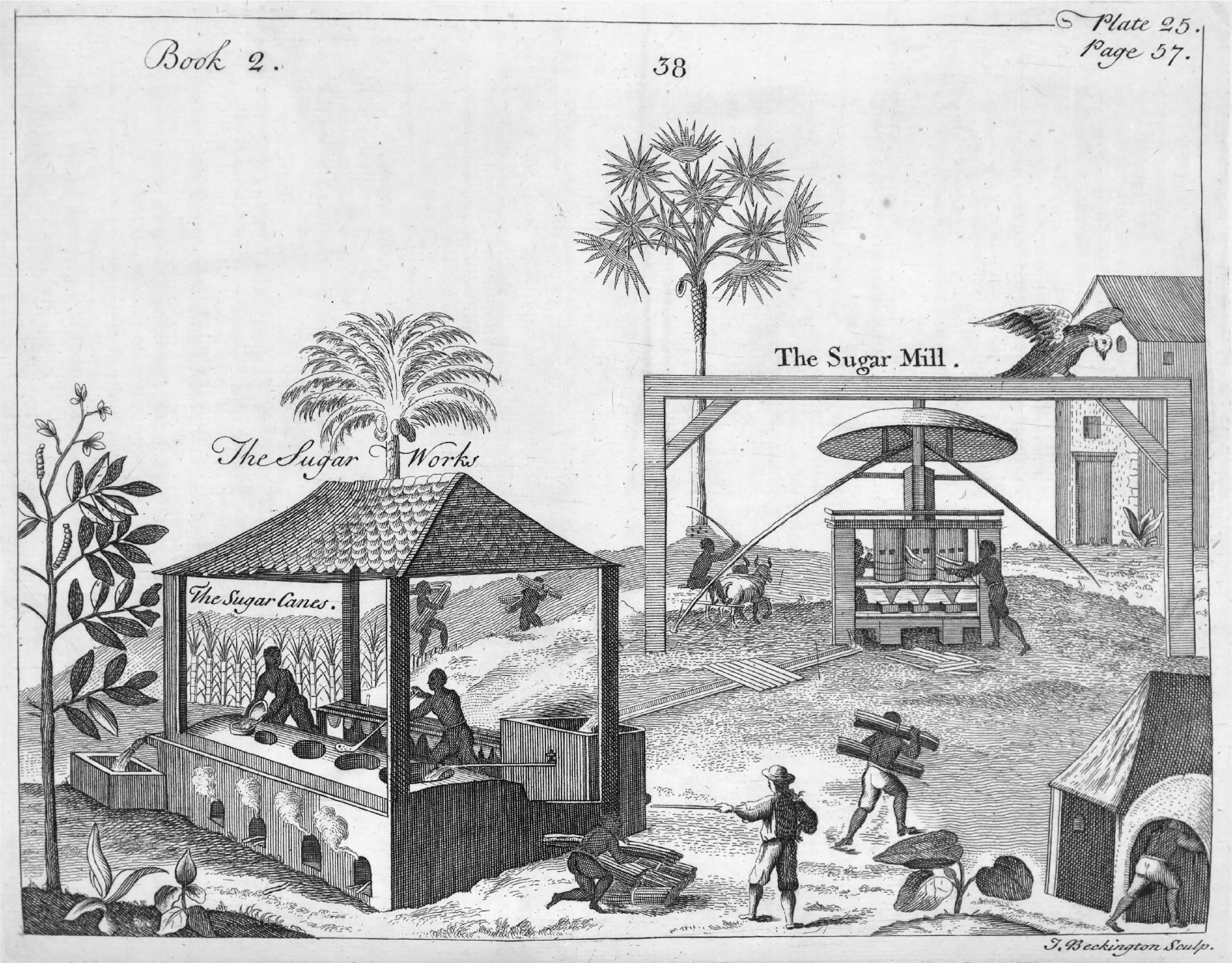

The Bordeaux competition on the source of blackness did not occur in an intellectual vacuum, of course; it emerged in tandem with the ever-growing dependence of European economies on African slave labor throughout the New World. It is important to note, in fact, that in 1741the year when the essays arrived at the Royal Academy62,485 African captive men, women, and children are estimated to have boarded ships in chains along the long west coast of Africa, destined for plantations in Brazil, Central America, the Caribbean, and North America. As was invariably the case, a disturbing percentage of these humans died before spotting shore9,454 in this year alone. Although the trans-Atlantic slave trade had not yet reached its peak, the number of Africans who had been forced to make this dreaded voyage already totaled well over four million. By the end of the eighteenth century, the era we have come to know as the Enlightenment, another 4,500,000 Africans were forced to leave their home continent for a life of brutal enslavement in plantations on the other side of the Atlantic. (See https://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates.)

The imperatives and advantages of Frances slave-based colonies in the Caribbean were patently obvious to every member of the Bordeaux Academy in the 1730s. Yet the question they ultimately decided upon for the prize-problem of 1741 centered solely on black bodies themselves, as if the reality of Africans enslavement in the Caribbean (not least in the city of Bordeaux) was not pertinent. This competition format, in short, not only obscured the citys and Frances relation to New World slavery, it also hid the fact that the color of sub-Saharan bodies had become synonymous with human bondage. Lurking behind the framing of the academys competition were thus two metonyms: in addition to the fact that the color black was a metonym for Africans, Black Africans themselves were undoubtedly a metonym for slavery and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

To a large extent, the Bordeaux contest was only the latest iteration of a two-thousand-year-old fascination with dark skin. When the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Arabic peoples first described the black-skinned inhabitants of Africa, it was inevitably Africans color that was the most striking takeaway. Over the centuries, African blackness had grown into an all-encompassing signifier that substituted itself for the range of reddish, yellowish, and blackish-brown colors that the skin colors of Africans actually express. Indeed, the notion of blackness had even become synonymous with the land itself: a number of the geographical names that outsiders ultimately assigned to sub-Saharan Africathese include Guinea, Niger, Nigritia, Sudan, and Zanzibarcontain the etymological roots of the word black. The most telling example of this darkened-inscribed geography is the word Ethiopia. Derived from the Greek, aitho (I burn) and ops (face), this term not only became one of the most widespread labels for the entire sub-Saharan portion of the continent until the late seventeenth century, it even hinted at a theory about the original cause of blackness itself.

The members of the Bordeaux Royal Academy of Sciences had obviously become puzzled by the mishmash of conflicting explanations for African pigmentation. To begin with, they were well aware of bioclimatic accounts dating from Antiquity that maintained that the heat, sun, and humidity of the Torrid Zone not only had darkened African skin, but may have thrown African bodies out of equilibrium, introducing humoral imbalances that produced an excess of black bile and melancholia. These naturalist explanations existed alongside sacred history or what we might call European biblical anthropology: both the Old Testamentinspired belief that all humans descended from Noahs three sons and the notion that Black Africans were actually an ill-fated branch of the family, the result of a curse that not only marked them but sentenced them to slavery. In addition to both climatological and biblical explanations, the Bordeaux Academy members had heard about new scientific discoveries and theories related to Africans: anatomists were sending back reports of anatomical dissections of slaves from the colonies; naturalists were putting forth secular histories of human mutation; and taxonomy-minded thinkers had begun proposing human classification schemes that separated the worlds peoples into