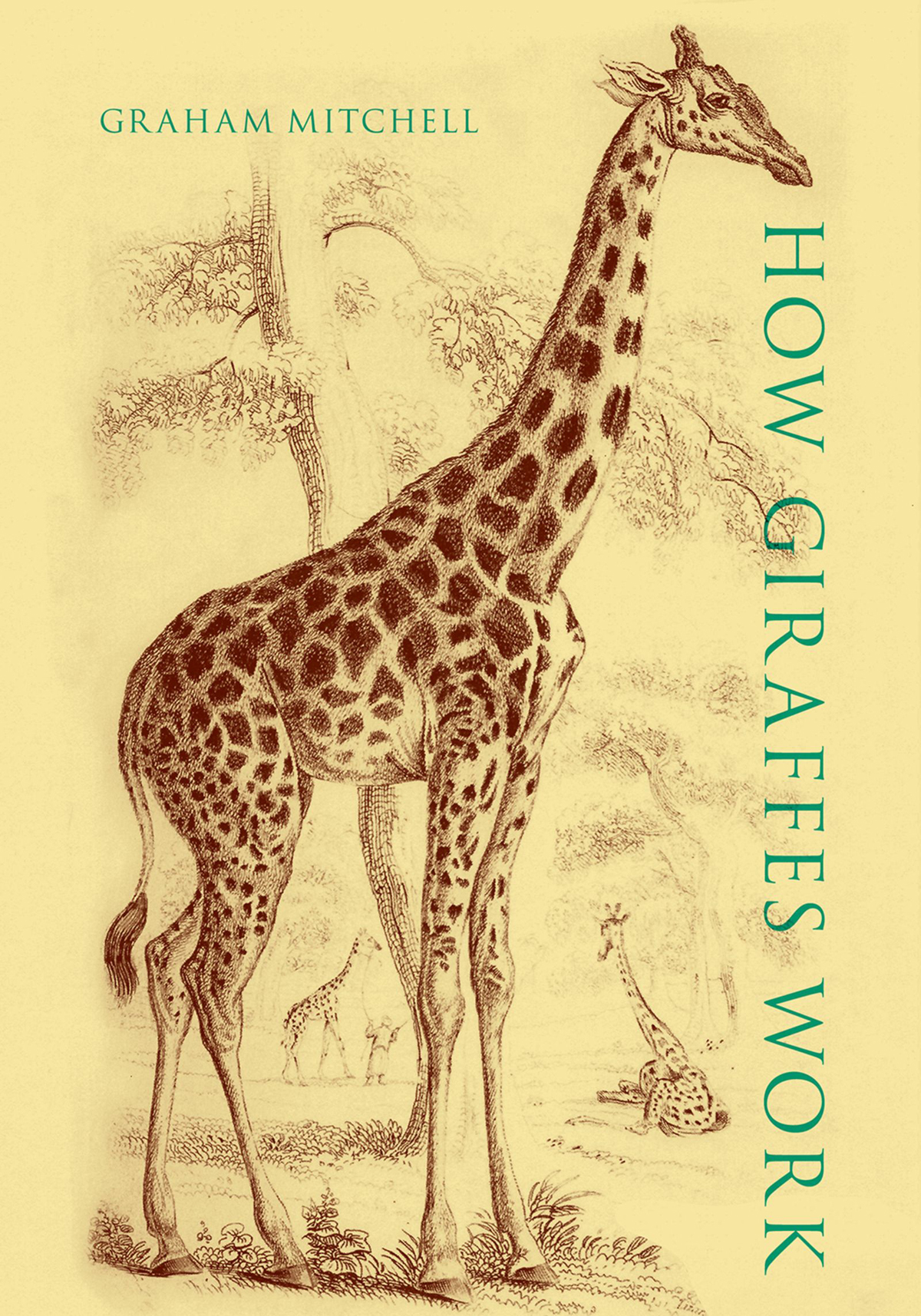

How Giraffes Work

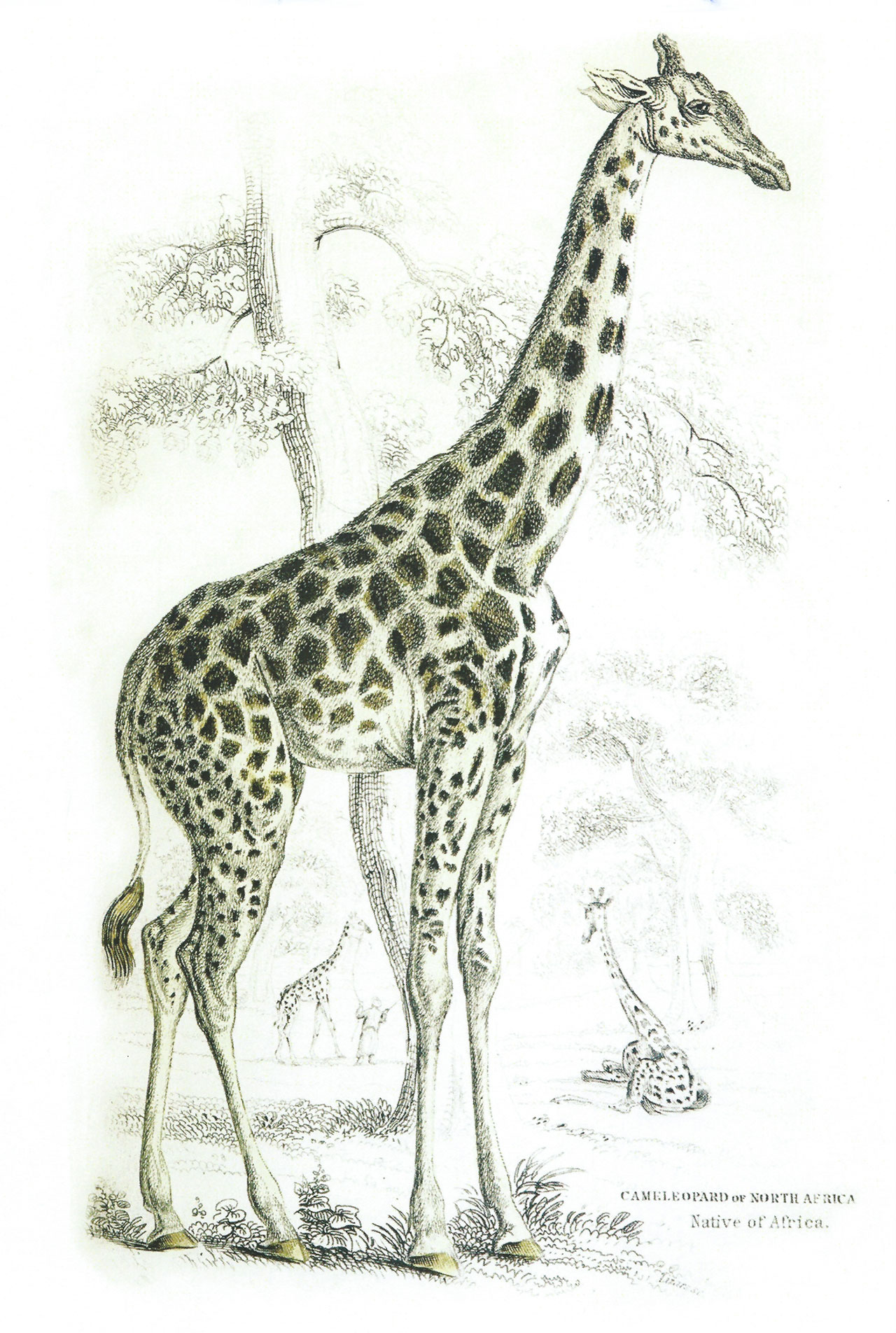

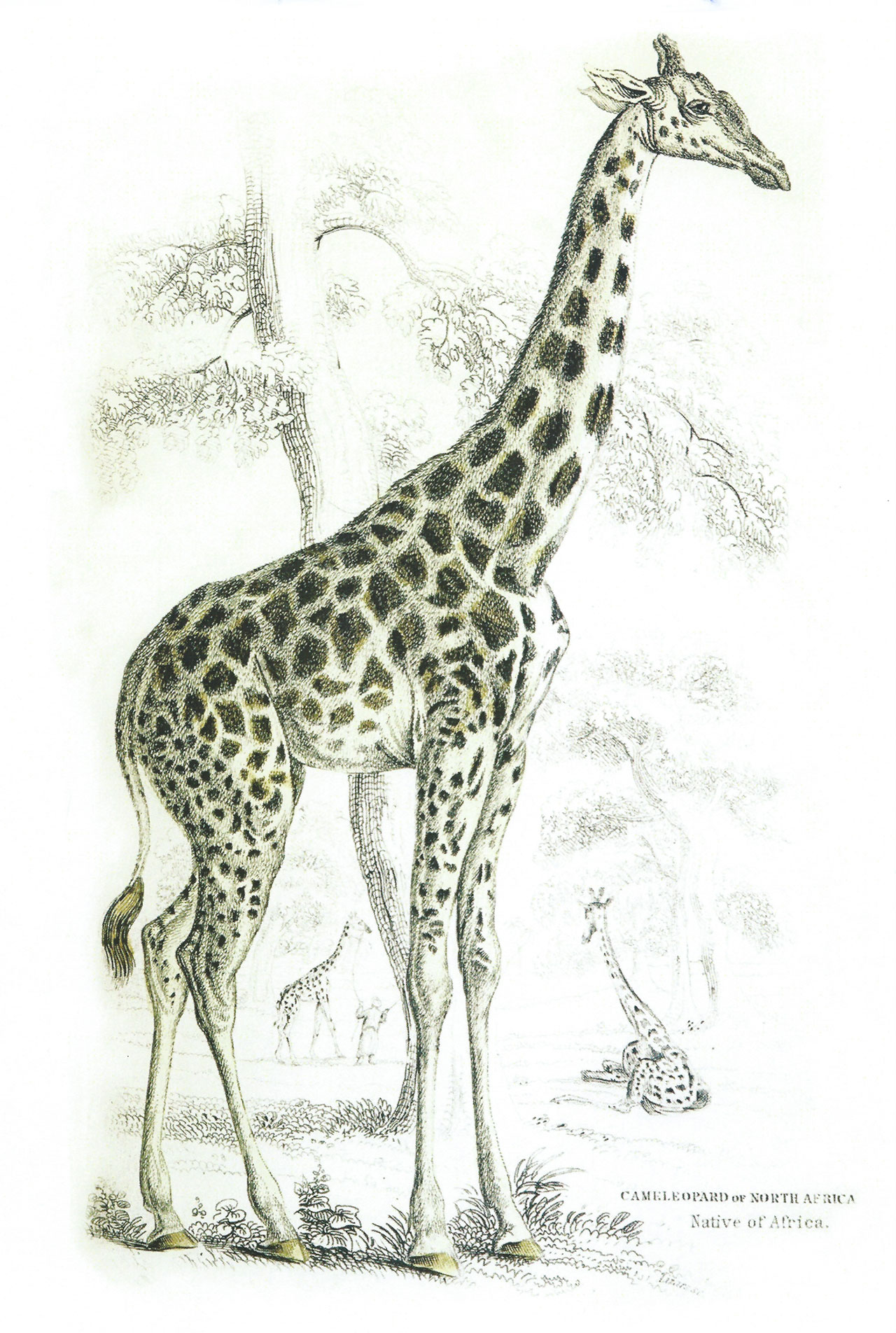

Giraffa camelopardalis typica. Jardines Giraffe.

From . Courtesy of Tony Ridge.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mitchell, Graham, 1944- author.

Title: How giraffes work / Graham Mitchell.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020057172 (print) | LCCN 2020057173 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780197571194 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197571217 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Giraffe. | GiraffeConservation.

Classification: LCC QL737.U56 M58 2021 (print) | LCC QL737.U56 (ebook) |

DDC 599.638dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057172

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057173

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197571194.001.0001

For Keith, Carolyn, Andrew, and Heather and all who follow them

Contents

No one likes an unsolved mystery. Giraffes are a mystery. And they are unique. Where did they come from? How do they work? Magnificent in its attire, bizarre in its shape, singular in its walk, colossal in its proportions, inoffensive in character, the giraffe has long attracted the attention of man. There is no individual of the animal kingdom more worthy of a monograph. So wrote Joly and Lavocat in 1846 in their monograph. I share their sentiments. There are few creatures more beautiful, more aloof, and more fascinating than giraffes. They seem to have reached that rare combination of contentment and serenity that we all strive for. Richard Lydekker, a Victorian zoologist, was equally impressed. He wrote in 1901, [It is} one of the most strikingly beautiful animals in the creation. However, a giraffes life is not an easy one. It is in the words of Ray Lankester in 1908, another distinguished Victorian zoologist, altogether exceptional, novel, and specialised and they have to be to survive.

Much has been written about the public lives of giraffes, and their history in art and diplomacy, and it has been well recorded in books (e.g., complex. Doing it justice in a relatively short book is and was a challenge, not least because studies on and scientific articles about giraffes are ongoing, keeping up with them a constant task, and books must have an end. Readers, both friend and foe, will judge the success of this attempt to do so. In many ways this book is a mystery tale, a tale of investigation and of analysis that tells of what we know and what we could find out if we wanted to, but I think that there comes a point in the study of animals where we should stop short of full knowledge, admire the knowledge that we have, and speculate on the knowledge we do not have. That is the point I have reached. It has been a personal obsession to reach it, and the story is personal too and written prodesse et delectare. I hope any reader finds that it rings true.

My earliest memory of a wild giraffe was a picture taken by my father of a giraffe that had tripped, fallen, and broken its neck while trying to leap a fence in the then Eastern Transvaal Lowveld of South Africa, a place rich in history and as romantic as any. I was to discover much later that accidents of that sort are not uncommon among giraffes, but the struggles of that giraffe and its tragedy as captured in that photograph have never left me, and why that accident happened and why its consequences were so severe have been thoughts never very far away throughout the time I have studied giraffes. Although this is a book about the physiology and anatomy of extant giraffes or, in other words, about how modern giraffes work, the most frequent questions asked about giraffes are not about how they work, but how their shape came about. All three of the scientistsDarwin, Wallace, and Lamarckwho in the nineteenth century pondered the question of how the shape of an animal develops and how a species originates used giraffes to illustrate their ideas. Their answers were theoretical. Fossils of giraffes were few and gave no idea of who the ancestors of modern giraffes were that bequeathed their characters to their offspring. When did those ancestors live, and where did they live? What were the selection pressures then that resulted in their shape now? What advantages did and does their shape give them so that they can survive successfully? Their survival is usually attributed to their great height and unique markings, but it is the functional anatomy or morphophysiology of these extraordinary creatures that has contributed most to their survival. What were/are they? Answers to that question have been the subject of many, many years of research. It is a story filled not only with a unique creature, with geography, and climate changes of great magnitude, but also by the labors of extraordinary people who put many pieces of the puzzle together. Very often the language they used to describe their observations far defeats the best efforts I could make, so in many places I have allowed them to speak for themselves, when they, like Cortez, saw a peak in Darien. Throughout this book I have tried to interpret the best scholarship, some of it difficult to understand and much of it hidden from public view in the pages of learned scientific journals. Often that scholarship is in the indigestible form much loved by scientific journals and so, despite being relevant and interesting, it is simply unknown and unappreciated. One consequence is that the information that seeps out of dusty pages is oversimplified into easily understandable myths. All this I have tried to correct, but in doing so I have almost certainly made errors of interpretation which no doubt many will detect with glee. Many references have been used to acquire the information recorded in this book. I am certain that others should have been read, marked, learned, inwardly digested, noted, and used, and others are still being published and just not read. My apologies to those authors whose work, highly relevant and useful, has been overlooked and thus not acknowledged. This book is also an opportunity to correct the many errors I and my colleagues have made in published articles. Hindsight is a source of acute embarrassment. In telling this story of giraffes, I have followed a historical approach to reveal how the knowledge progressed, and wherever possible I have used original diagrams to illustrate aspects of giraffe physiology and anatomy. This book cannot be complete or indeed accurate. Science is a demanding enterprise and will not allow a study to reach an endpoint or finality, and will not allow us to say we now know everything there is to know.