Published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by

OXBOW BOOKS

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Robert Hensey 2015

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-951-7

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-952-4

Kindle Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-953-1

PDF Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-954-8

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed in the United Kingdom by Short Run Press, Exeter

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

| United Kingdom | United States of America |

| Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

| Telephone (01865) 241249 | Telephone (800) 791-9354 |

| Fax (01865) 794449 | Fax (610) 853-9146 |

| Email: | Email: |

| www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate group

Front cover: Photograph courtesy of Robert Ardill, www.IrelandUpClose.com.

I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape Something waits beneath it, the whole story doesnt show.

Andrew Wyeth (1965)

What happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new.

T. S. Eliot (1921)

OXBOW INSIGHTS IN ARCHAEOLOGY

EDITORIAL BOARD

Richard Bradley Chair

Umberto Albarella

John Baines

Ofer Bar-Yosef

Chris Gosden

Simon James

Neil Price

Anthony Snodgrass

Rick Schulting

Mark White

Alasdair Whittle

Preface

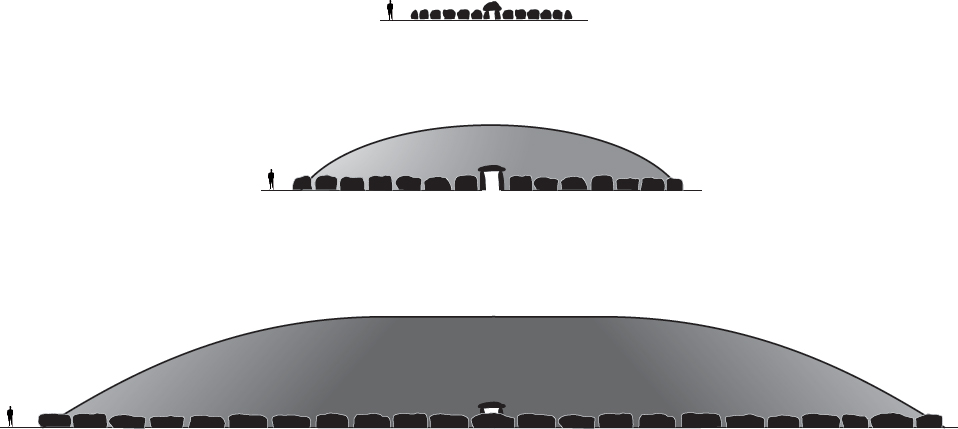

I remember the first time I entered Newgrange. Taking in its great splendour and having no response but to laugh at the impossibility of it all. Two hundred thousand tonnes of stone all told, so ancient, and yet, science fiction-like, designed to allow the entry of a narrow beam of winter solstice light. What was it for? Where could such skill, such extraordinary ambition have come from?

I once had a Shakespeare lecturer, a well-known dramatist in his own right, who engaged his classes attention by announcing he would impart the secrets to understanding King Lear. Pacing across the vast stage of the Aula Maxima he proclaimed in front of the four hundred eager students pens alert on their first day to make sure any crucial information was not left unrecorded that To understand King Lear one has to dramatic pause first know Hamlet. He continued, To understand Hamlet one has to dramatic pause know Richard III. And so it went, after each dramatic pause, he listed another famous Shakespearean play until the students got the point.

Such is the case with archaeology, too. There is, I believe, a kind of knowledge that can be acquired through examining a great many related sites, seeing them at different times of year, in different weather conditions, from different perspectives. One can slowly take in subtle details of a monument or place, sometimes unconsciously. This soft knowledge compliments and informs the hard knowledge that is the conventional goal and output of archaeological work. For instance, one could observe a slightly unusual tilt of a capstone not present at other sites and know, instinctively, it has been moved in the past, perhaps pushed aside in the course of antiquarian investigations and clumsily replaced. Observing poorly completed work and mistakes from the past can also be illuminating, sometimes allowing our ).

At the time of that first visit to Newgrange I was only dimly aware of similar sites in the west of Ireland, less sophisticated equivalents, but few or no information or publications on those monuments were readily available in the public sphere. Then in mid-1990s as the Internet was becoming more utilised, discoveries from the second campaign of excavations at the Carrowmore passage tomb complex, County Sligo (and intriguingly early dates) were placed online. The speed at which information from those excavations was released seemed almost instantaneous compared with the usual pace of archaeological publication. The excitement around the Carrowmore work and findings encouraged me to visit the site, and subsequently similar monuments in the west of Ireland and nationally. As I became familiar with greater numbers of passage tombs, I came to believe that the monuments outside of the Boyne Valley possessed valuable pieces of the Newgrange puzzle. Each new site studied changed and deepened ones understanding. Not that one needs personal experience of every passage tomb on the island, but after many years considering these monuments I came to the conclusion that Newgrange cannot be comprehended without an in-depth knowledge of at least all four major passage tomb complexes (which between them contain approximately half of all Irish passage tombs).

As I have attempted to show in this book, especially in the opening chapters, the most westerly cluster at Carrowmore has a particularly important role in understanding the history of the Irish passage tomb tradition in Ireland, but so too do the monuments at the other major complexes, and not least the other monuments which neighbour Newgrange within the Br na Binne complex. When considered as a group, the passage tombs of Ireland can also provide unexpected insights into the beliefs, concerns and religious activities of communities in the Neolithic not apparent when a single monument is examined in isolation. Ultimately, Newgrange is a materialisation of a lengthy evolution of the beliefs and thought-worlds of the communities which constructed passage tombs through time.

As is the case for many authors, in hindsight I realise I have written the book I wanted to read at the beginning of this journey, after that first visit to Newgrange, one that could begin to address where Newgrange came from, why it is there at all.