EXPLORATIONS IN ANTHROPOLOGY

A University College London Series

Series Editors: Barbara Bender, John Gledhill and Bruce Kapferer

First published 1997 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Neil Jarman 1997

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by JS Typesetting, Wellingborough, Northants.

ISBN 13: 978-1-8597-3124-6 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-8597-3129-1 (pbk)

My research into parades and visual displays in Northern Ireland began in the summer of 1990 for an undergraduate dissertation at the Department of Anthropology at University College London; it has steadily continued through my Ph.D. work, on which this book is based, into more policy-orientated research into parades as a political problem, on which I am working at present. My funding has come from a number of sources. I began with a local authority undergraduate grant from the London Borough of Newham (without which I would never have gone to university as a mature student). Postgraduate work at UCL was initially supported with a grant from the Central Research Fund of the University of London and then with a three-year research grant from the Economic and Social Research Council. Postdoctoral work has been supported by a Fellowship from the Cultural Traditions Group held at the Department of Social Anthropology at Queens University, Belfast and by research work at the Centre for the Study of Conflict at the University of Ulster at Coleraine. I am extremely grateful to all of these bodies and organisations and the many people within them who have assisted my work.

There are always too many people to thank for their support and encouragement, and I hope there will be no offence taken by those whom I do not mention. I just want to acknowledge a few people to whom I owe a special thanks. In London, Danny Miller and Barbara Bender, among the staff at UCL, have given me many years of help and encouragement, as well as supportive and critical readings of my work. In Belfast I have worked extensively with Dominic Bryan, since he first gave me a lift to a Hibernian parade in Draperstown in March 1993. Although we have largely pursued our separate research agendas, he has been of immense assistance in helping me to maintain, and to extend, my interest in the subject.

Finally, I want to thank Maggie, Kyle and Ruari, for putting up with my seemingly endless visits to parades in odd locations, and without whom none of this would have happened.

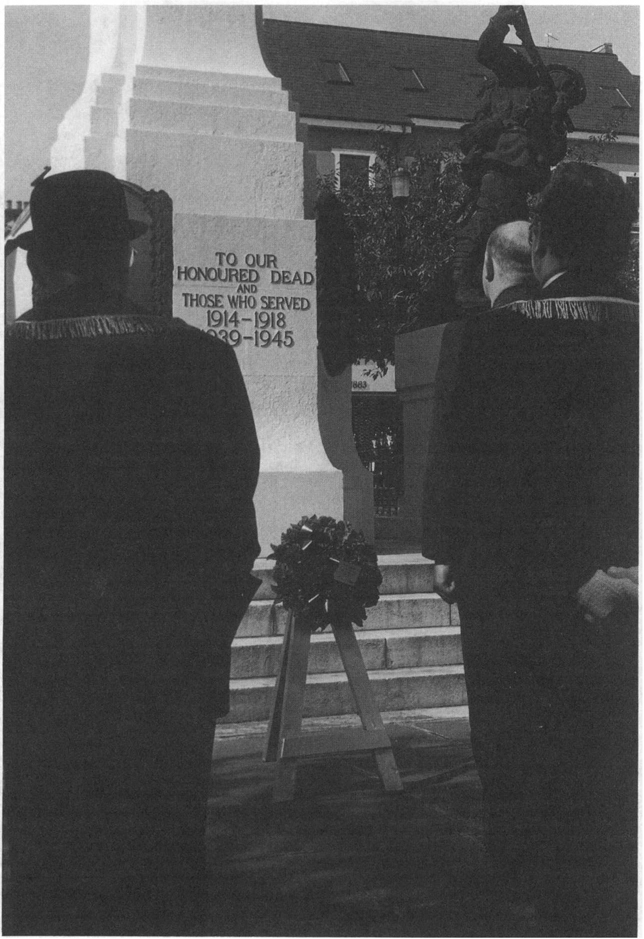

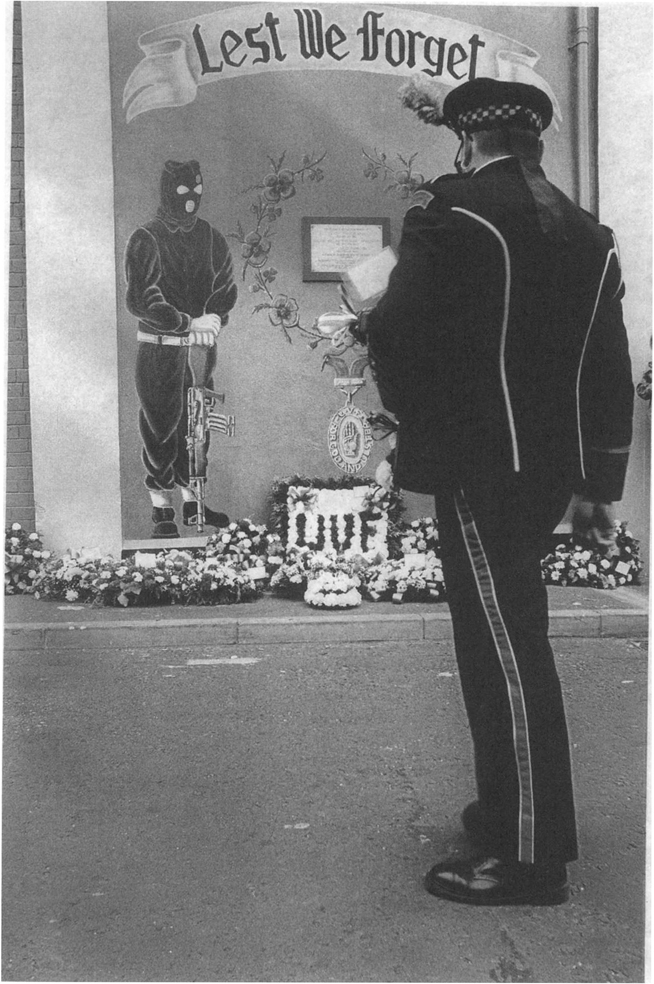

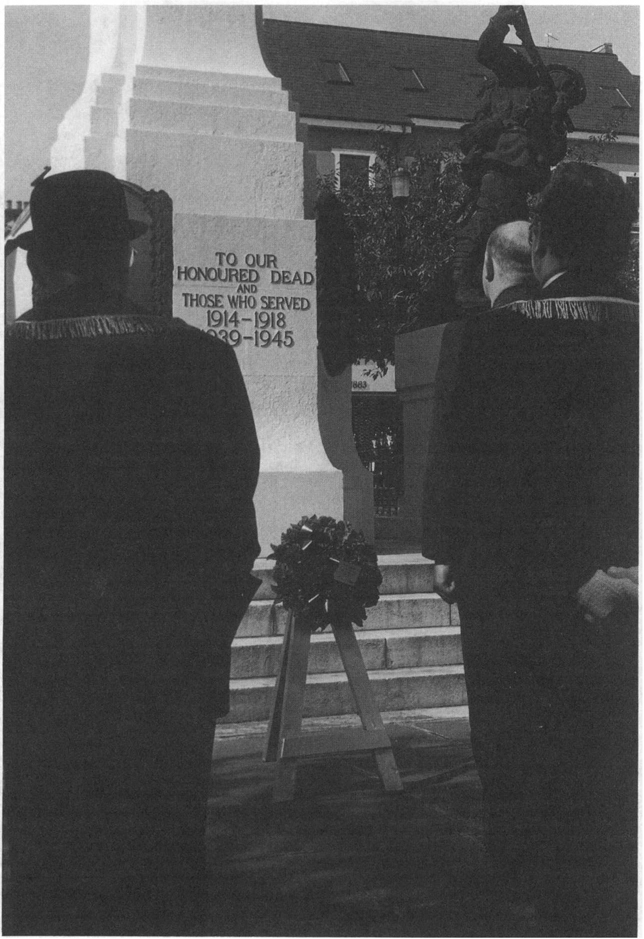

Remembering I, Apprentice Boys, Londonderry, August 1992.

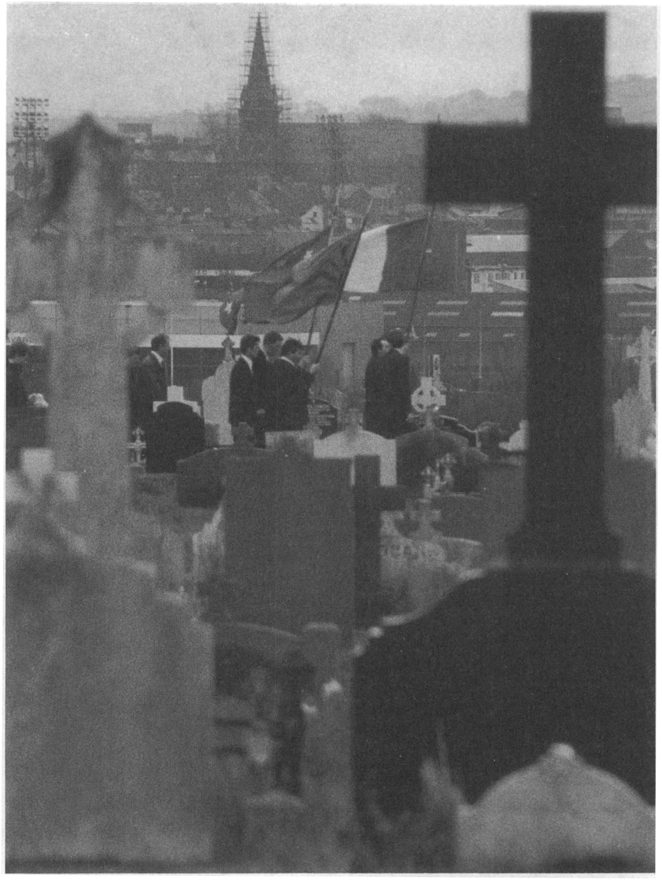

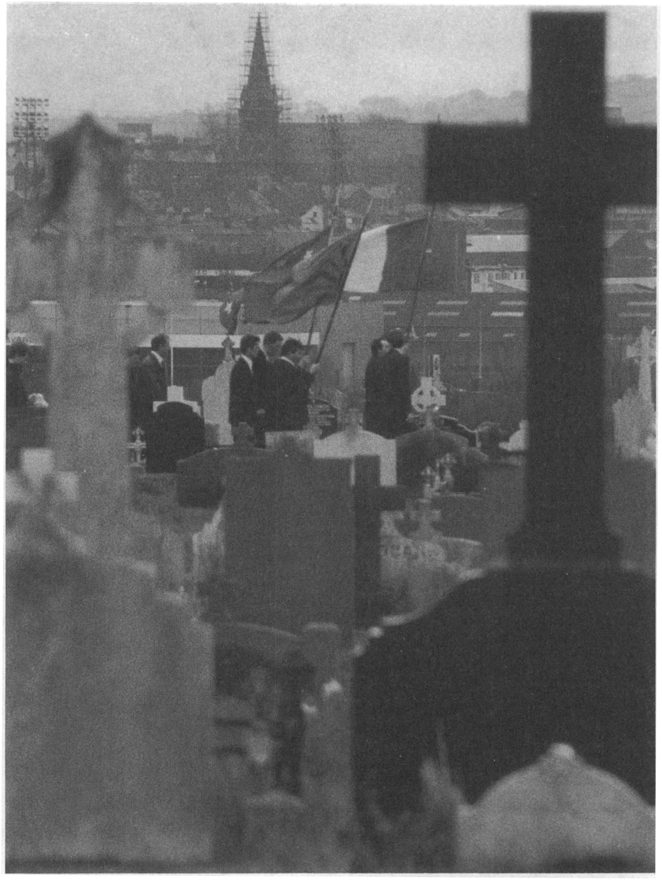

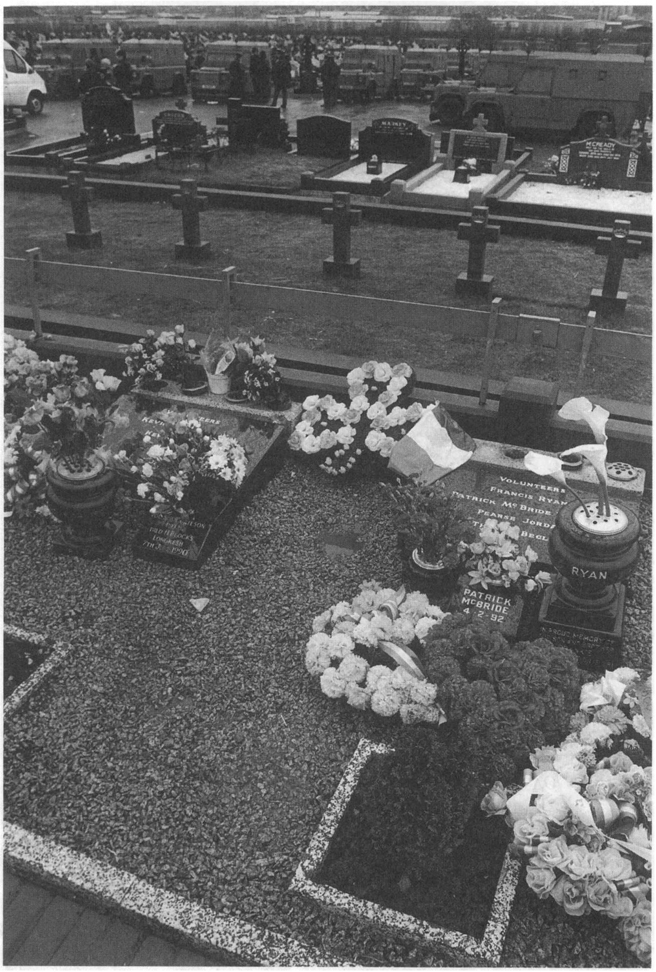

Remembering II, Workers Party, Milltown, Easter 1993.

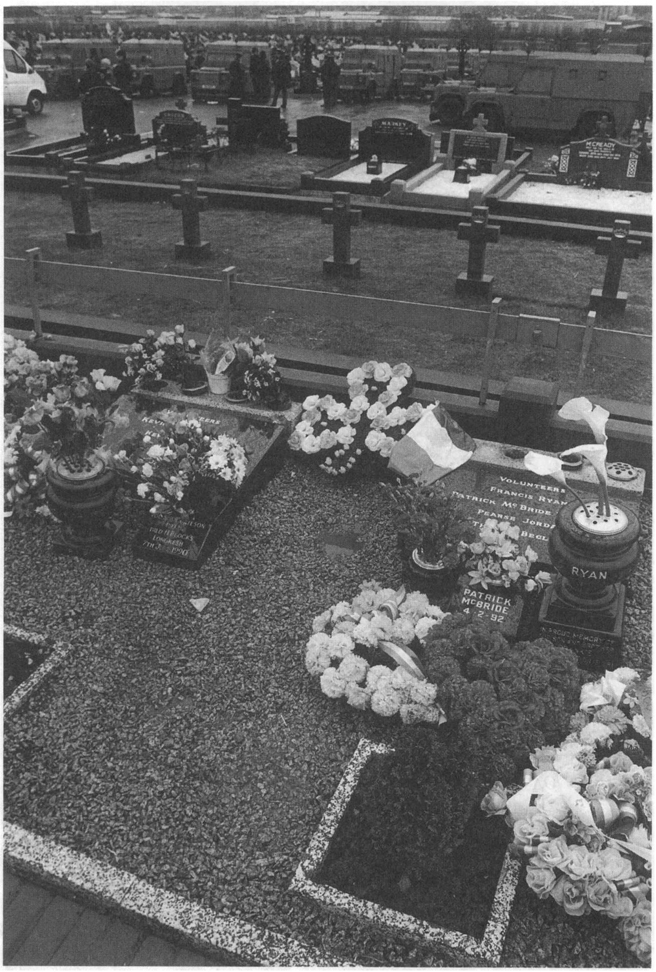

Remembering III, Sinn Fein, Milltown, Easter 1994.

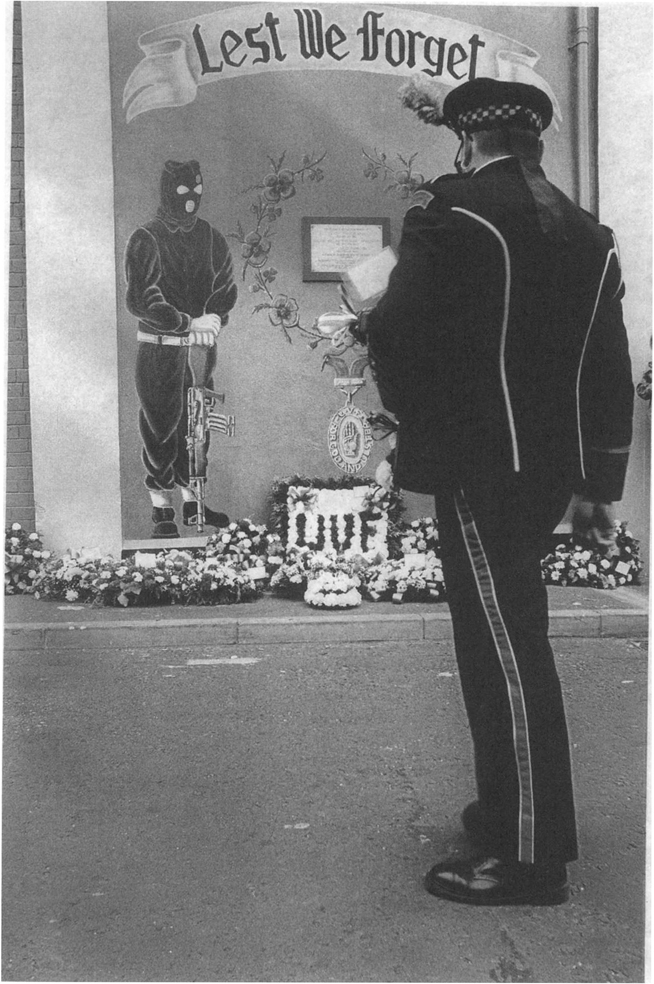

Remembering IV, Brian King Parade, Shankill, August 1995.

Chapter 1

The Performance of Memory

Some societies need no re-enactment to reactivate history; the process seems to be ingrained, habitual. Unassuaged injuries and injustices often lead men to conflate remote with recent times and even with the present. Many Irish continue to experience the Danish invasions, the devastations of Laud, the Famine of 1847, as almost contemporaneous events. Irish memory has been likened to historical paintings in which Virgil and Dante converse side by side. But the Irish do not live in the past; rather, Irelands history lives in the present. All previous traitors and all previous heroes remain alive in it, as in the bottomless memory of an OFaolin character in which one might see, though entangled beyond all hope of unravelling, the entire saga of Irelands decay

(Lowenthal 1986:250).

The above embodies a widely held view of the Irish use of history, in which the concept of folk or race memory is used to explain persistent or recurrent social beliefs and practices that are transmitted apparently almost without trace (MacDonagh 1983a; Rose 1971; Smyth 1992; Stewart 1989). Although the past retains an unusual prominence in Irish social and political life, can we talk of a bottomless memory in which nothing and no one is forgotten? Are such memories really sustained habitually with no re-enactment? How is it even possible to talk of a singular Irish memory in an island that has been subject to centuries of colonial domination, an island that now has two distinct, ideologically opposed ethnic communities? And what impact will the fact that the island has sustained a military conflict for the past generation in which one of the most prominent features has been the conflicting interpretations of Irish history, have on a sense of collective belonging? While one may criticise Lowenthals sweeping generalisation of the understanding and use that many Irish people have and make of their past, it is a perspective that can be accommodated within many popular interpretations of the Irish problem. Ireland is all too readily regarded as a society trapped in the past: the contemporary conflict has been likened to medieval religious wars, or alternatively described as an unresolvable conflict between two mutually hostile tribes. Both of these approaches consign the Irish (or perhaps only those Irish who live in the northern part of the island) to a primitive or backward state that in turn perhaps makes their irrational, bottomless memory more understandable.

However, no matter how critical or dismissive one might be of the religious war or tribal conflict approaches (Jenkins, Donnan and MacFarlane 1986), it is impossible to ignore the prominent role that historical events and characters continue to play in the political and social life of Northern Ireland. One might ask why battles of the seventeenth century are still remembered as important events 300 years later? Why does a seventeenth-century British king who is all but unknown in England feature as an icon of British identity in Northern Ireland? What do historical and mythological figures, such as King William III and St Patrick, mean to people living in the north of Ireland? How have the complex identities subsumed within the populist rhetoric of Protestant and Catholic been created, developed and maintained since the arrival of colonists from England and Scotland in the seventeenth century? And why are they the most prominent anchors for collective identities? This study considers these questions by analysing some of the ways and the means by which past events are remembered in contemporary Northern Ireland. It focuses in particular on the numerous commemorative parades that are held each year to explore just what is being commemorated and remembered at those times. In Britain the practice of holding annual parades, which flourished in the nineteenth century, has now largely died out; but in the north of Ireland the practice continues stronger than ever. In tracing the history of this custom, I aim to show how parades have been used in the past and how they have changed, and to indicate why these popular commemorations and festivities have not only survived but are thriving in Ireland, when similar events have failed to survive the transition to urbanism and industrialisation in other Western European and North American countries (Burke 1978; Cressy 1989; Davis 1986; Malcolmson 1973; Storch 1982).