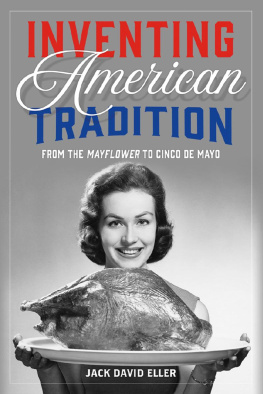

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2018

Copyright Jack David Eller 2018

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page References in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index Match the Printed Edition of this Book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789140354

Preface

O nce upon a time there were no American traditions. But, then, once upon a time there was no America. There was surely a continent west of the Atlantic Ocean, but no one called it America, and there were surely people inhabiting that continent, but none of them called themselves American. Americathe country or the identitywas invented fairly recently. The people who migrated from Europe, and then eventually from every other part of the world, to what would become America or the United States brought traditions with them; those traditions were European, African, Asian, and so ontraditions in America rather than American traditions. At the moment of American independence, there were few, if any, traditions that were originally and uniquely American.

It may sound counterintuitive to speak of invented traditions. In our day of fake news and post-truth arguments and assertions, though, it is not preposterous to consider how humans fashion and inhabit their own realitieseven more so than in previous eras, when knowledge was less certain and the pathways of knowledge were unreliable at best. Granted, the traditional idea of tradition implies (often, if not usually, spurious) continuity with the ancient past. The United States, however, has no ancient past; it is a society and country self-consciously created in the late eighteenth century but by no means completed in that era. It took many decades for the U.S. to accumulateand to reflect on and fret aboutthe experiences out of which tradition was constructed.

And America is hardly unique in this regard. Even traditional societies, which are sometimes imagined to be primordial and static, even ahistorical, have actually been dynamic and changing. This is certainly true of the native nations of North America, who had their own traditions, many not as traditional as we often assume. For instance, the Iroquois Confederacy of the northeast of the U.S. was not formed until the 1500s, shortly before Dutch and English settlers began arriving in numbers in their territory; after a period of intertribal war, a man of peace appeared, known to history as Dekanawida or Tekana:wita, The Great Peacemaker, traveling with a companion named Hahyonhwatha or Ayenwatha (made famous in Henry Wadsworth Longfellows epic poem The Song of Hiawatha). The very name Iroquois is an invention and imposition, applied to them by the French; they called themselves Haudenosaunee or Ongwanonsionni, which means something like the people of the longhouse. The western Plains culture is another example of a tradition that could not have existed far into the past; the classic horse-riding culture of groups like the Cheyenne and Lakota was an innovation, since horses were not indigenous to the Western Hemisphere. Only after horses were brought to and released on the continent could Native Americans begin riding them, so this tradition is an adaptation to a foreign introduction. Worse still is the fact that historical, linguistic, and archaeological evidence indicates that some of these groups, such as the Cheyenne, were not even indigenous to the West but migrated there because of population pressures brought on by European settlement.

Around the world, the story is the same. Traditions that appear or claim to hearken back to time immemorial prove to be creations, often in the quite recent past. The very societies themselves that purport to be traditional turn out to be products of contemporary forces. Anthropologists Meyer Fortes and E. E. Evans-Pritchard, for instance, commented in 1940 that some of the supposed traditional tribes of Africa in actuality appear to be an amalgam of different people, each aware of its unique origin and history, often forged by European colonialism on the continent. inventing and joining a traditional society.

The Melungeons are but one example of the fertile productivity of tradition-invention in the United States, a country and society that is itself, as mentioned above, thoroughly a recent achievement. And in a very real sense, the business of inventing American tradition could not commence until America itself was born, making many of those traditions of much later vintagesome no more than a few decades old and hardly any of them more than a century-and-a-half old. This book tells the story of a few of the signature traditions of American society. It does not attempt to be exhaustive; that would be impossible for a book of portable size, if not for an entire series or encyclopedia. I have made a selection of some of the most familiar, important, and revealing traditions in America. I have only included traditions that originated in America, which, for instance, excludes Christmas; assuredly, Americans do Christmas, and in a distinctly American way, but Christmas is not a fundamentally American tradition. I have also not included some domains of tradition, such as sports or music, which could easily filland have filledvolumes on their own. Finally, I have not included religion, although America has been the site of the invention of some prominent religions, from Mormonism and Seventh-Day Adventism to Scientology. I offer instead a sampling to make a point.

Further, this book does not strive to excavate the true history of the traditions, partly because their history is often shrouded in uncertainty and controversy and partly because there often is no true history. That is, we are not in search of the first Thanksgiving or the real national anthem, because the first or real one is not the main point (and, in the case of national anthems, there is no real one). As often as not, the myth and legend is as importantand revealingas the facts. The question is how a tradition gets started, transmitted, altered, and adopted. Many people contribute to a tradition, for many (often extremely partisan) reasons, and there is almost always a struggle over tradition. The outcome of the processwhat we will call the traditioning processis by no means assured. Nor should we ever consider the traditioning process finished.

![Eller - The gluten free gourmand : [a little cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/92634/thumbs/eller-the-gluten-free-gourmand-a-little.jpg)