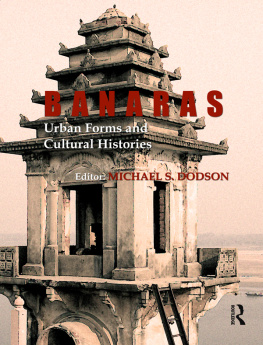

First published 2012 in India

by Routledge

912 Tolstoy House, 1517 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001

Simultaneously published in the UK

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN

First issued in paperback 2015

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2012 Michael S. Dodson

Typeset by

Star Compugraphics Private Limited

5, CSC, Near City Apartments

Vasundhara Enclave

Delhi 110 096

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-66006-9 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-69377-6 (hbk)

Banaras is a city which, for visitors and residents alike, elicits complicated feelings. It is, moreover, a city of stark contradictions. Its antiquity sits in contrast to the recent nature of much of its built structure, while its spiritual reputation coexists uneasily with the din of its crowded streets and the push of its vendors and touts. But for those who love Banaras, its pull is unceasing, and time spent away from its streets and its people is time which moves too slowly in anticipation of a return. It is, perhaps, the contradictions and complexities of the place which constitute its appeal for many the knowledge that no matter how much one knows of this city, there is always more to learn, another alleyway to explore, another building to discover, and more people to meet. It is a city where I have found the most extraordinary beauty in the most unexpected of places in the sudden quiet of a flooded street, waves washing against the wheels of a cycle rickshaw and the most wonderful, open, and inviting of people. But Banaras is also home to the most appalling of poverty, social disenfranchisement, and environmental degradation. A life lived in Banaras is, then, not easily classifiable or easily summarized, though it might be said that it is, at the very least, rarely unstimulating.

Despite the many popular and academic representations of Banaras as somehow timeless and eternal, as sacred and dominantly (or even exclusively) Hindu, and as a unique urban site conducive to spiritual awakening, it is a city like most others in northern India, in that it faces a myriad contemporary challenges, often of the most mundane kind. The residents of this city now struggle on a daily basis with a physical infrastructure woefully inadequate for its growing size and increasing density. For a modern city of perhaps two million people, the services which urban authorities are able to provide fall far short of even north Indian standards: electricity is intermittent; sewage remains mostly untreated; the River Ganga is here septic; and safe drinking water access is decidedly incomplete. The citys rapid growth in recent decades has, moreover, promoted near grid-lock on the streets; a situation likely only to be compounded with the introduction of ever more automobiles. Economic development and diversification in the city remains limited, even in the face of a silk weaving industry being decimated by cheap Chinese imports, while the draw of easy money from the tourism trade distorts several elements of urban society. Communal violence and terrorism continues to plague this decidedly multi-religious city intermittently, while the ambiguities and perceived incompleteness of shared religious space (such as the site of the Vishvanath Mandir and Gyanvapi Masjid) still threaten, at times, to promote conflict. The historic structures of Banaras are also constantly under threat from demolition, neglect, or unsuitable development, given the enormous pressures of inflated property prices, poor housing stocks, urban migration, and international tourism. Local government is overwhelmed and underfunded, spending much of its energy and limited funds attempting simply to maintain the status quo, although of late the Uttar Pradesh state government and the Varanasi Development Authority (VDA) have concocted some radical, and in the eyes of many (myself included), radically inappropriate plans to transform the face and structure of Banaras through flyovers and multi-storey parking garages. In the meantime, property developers routinely ignore the byelaws which restrict new building close to the river and to sites of historical importance, blighting the riverfront, especially, with a range of cheaply constructed and ill-suited structures. One might enumerate here the new hotel which towers over the eighteenth-century astronomical observatory at Manmandir Ghat, and the frankly hideous white box now perched atop the dangerously dilapidated Balaji Mandir, just south of Panchaganga Ghat.

Banarass problems reflect many of the challenges which India as a whole faces, and the strategies to address them are likely to be at least as complex as the problems themselves, with many economic, social, and cultural components to be considered. This book includes essays by a range of historians who feel personally committed to this city and its people, to the elucidation of its past, and to conceiving the betterment of its future, but (hopefully) without the romanticization which so often accompanies writing about this place. In particular, the essays presented here are devoted principally to a historicization of Banarass urban character through an examination of the processes of British imperialism. All emphasize Banarass qualities as an enormously complex space of cultural and social interaction, economic and political activity, and urban vitality. When we touch on the religious it is with a view to understanding the construction of religious meaning in particular historical and social contexts, without a valorization of a sui generis link between the city and any particular religious tradition. In this respect, it is worth noting here that studies of the history of Islam in Banaras remain relatively hard to come by, at least in comparison to those that examine the citys link to Hindu tradition. And while I am pleased, as editor, to point to the work of Chris Lee on Banarsi Muslim poetry here, as well as to a number of other contributors engagements with Islam in Banaras, I regret that it was not found possible to include even more material of this kind in this volume. Needless to say, I hope that this book might also help others to think more extensively about the roles of Islam in forming Banarass complex, composite historical identity. Lastly, it is hoped that, through the inclusion of a range of contemporary photographs, a further function of this book will be to call a renewed attention to the fragile nature of this citys urban fabric, its social spaces, environmental quality, and historic structures. Ultimately, then, we think of this book as serving as a prompting to those with an academic or historic interest in Banaras to also think, write, and actively work on behalf of its present and future inhabitants. In this regard, the editing of this book is my own first contribution to engendering a wider appreciation of the historical trajectories, and also future possibilities, of a city that I have come to call my second home.