Acknowledgements

M y thanks go to David MacKinnon for his permission to use three of Gwendolyn MacEwens poems, and to Patricia Ningewance for permission to quote from her phrasebook of Ojibwe. The University of Toronto Press kindly allowed the reproduction of five pages from Percy Robinsons classic work, Toronto during the French Rgime . The National Gallery of Canada and Royal Ontario Museum both permitted the inclusion of pictures of valued artifacts. The City of Toronto Archives, Toronto Public Library, Archives of Ontario and Library and Archives Canada were all very helpful in providing images in the public domain.

I would particularly like to thank Dr. Mima Kapches, Cathy Crinnion, and Dr. Carl Benn who generously answered questions and offered advice. They bear no responsibility for any errors or oversimplifications I may have made in interpreting their expert opinions, and it goes without saying that they do not necessarily share any views presented in this book.

I thank my wife, Rose Kung, for her photographs and support. My final thanks go to Jane Gibson and Barry Penhale of Dundurn who have offered encouragement and guidance over the course of several years.

List of Maps

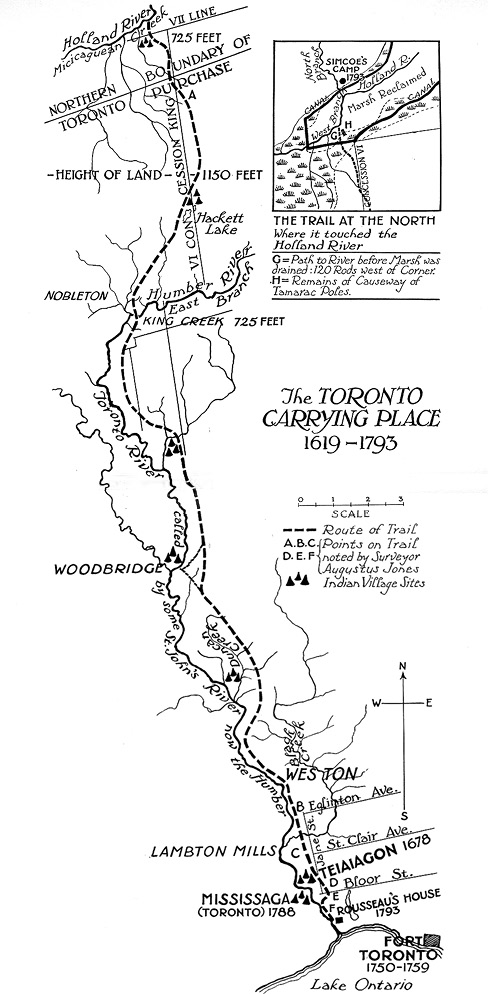

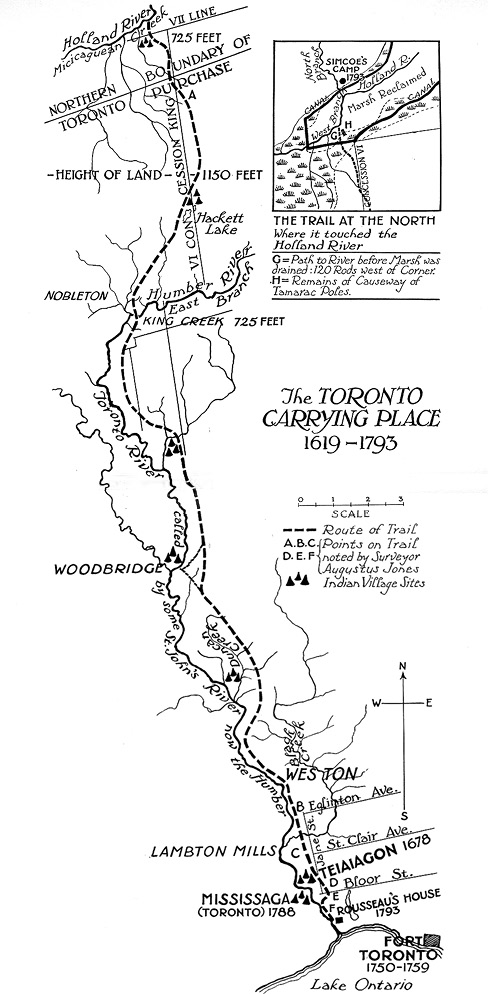

The Toronto Carrying Place 16191793 (by C.W. Jefferys)

Mouth of the Humber

Nations of Southern Ontario in 1600

Eastern and Western Branches of the Toronto Carrying Place

Three French posts at Toronto (by C.W. Jefferys)

Rousseau House to Teiaiagon

Dundas to Steeles

Woodbridge to Nobleton

King Road to Holland Marsh

Toronto & Georgian Bay Ship Canal proposed routes (by Kivas Tully)

(All maps by author unless otherwise noted)

Introduction

T he cemetery is right at the intersection of Baseline and Greenbank. Its an enormous site, sprawling over sixty acres of suburban Ottawa; a vast green space in the middle of the residential west end. As you go in from Baseline Road, the land rises suddenly in a wooded ridge. The trees on the slope and crest of the ridge are largely the pines after which Pinecrest Cemetery and Crematorium is named.

Only because of the ridge are the trees still here at all. Three corners of the intersection are dense with townhouses, apartment buildings, and a strip mall. The cemetery corner is much greener, but even here most of the trees have understandably given way to well-tended grass.

The only big stand of trees left is on the ridge. It is difficult to dig graves on a steep slope, and the cemetery planners sensibly decided long ago to leave the hillside in its original state. Like some living fossil the hillside wood has remained, essentially untouched, since long before there were settlers here.

At the foot of the ridge, not far from the cars on Baseline, a path leads into the wood. If you follow it, you enter at once into a different world, the sound of the traffic and the light of the twenty-first century slightly filtered through a hundred trees. The leaves crunch under your feet. Ahead of you in the gloom you can just about pick out the trail as it leads up through the wood to the top of the ridge. There is enough room for one person on the path single file Indian file, as we used to say when I was young.

It all feels so right. This is what the Native trails must have looked like, sounded like, smelt like, 400 years ago. This is straight out of The Last of the Mohicans .

Unfortunately it all comes to an abrupt halt when you emerge at the top seconds later, and find yourself in a modern, nicely groomed hilltop cemetery.

A plaque near the end of the path informs you that you have just walked part of a Native trail that led from the Ottawa River above the Deschnes Rapids to the Rideau River below the Black Creek Rapids. This portage would originally have been ten kilometres long, and would have taken about a day to travel. Now you can walk all twenty metres that are left of it in thirty seconds.

The Pinecrest Cemetery entrance to the tiny surviving stretch of Ottawas Black Rapids portage. Used by the Algonquin First Nation until well into the 1800s, this trail led from the Ottawa River to the Rideau River and allowed travellers arriving from the Northwest to get to Lake Ontario via the Rideau and a series of shorter portages. The famous Rideau Canal was completed by Colonel By in 1832 to replicate this route, much as Yonge Street was built by Lieutenant Governor Simcoe to reproduce the Toronto Carrying Place.

Ontario was once criss-crossed with these kinds of paths. While rivers have been the best highways in Canada for almost all of our history, there are some places you just cant paddle a canoe. Sometimes you need to portage from one river to another. Sometimes you need to go someplace where there arent navigable steams. So you follow a trail.

This book is about one of the most important of the Native trails in Ontario the Toronto Carrying Place, which stretched from the Holland River near Lake Simcoe to what is now Toronto. In its time, the Carrying Place was a well-known and well-used shortcut from Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence valley to the upper Great Lakes and the Northwest. Over countless years, the trail saw traders and warriors, First Nations and Europeans alike, hauling their cargoes through the woods.

But that was long ago. It has been four hundred years since the Carrying Place first entered recorded history, and over two hundred since it disappeared from the record. I am eager to go have a look, but after so long what could possibly be left? We are talking, remember, of a forest trail, a footpath worn into the ground, not some massive pyramid or even a paved road. As I write this, months before I head out into the field, it is not at all obvious to me that there will be anything left to see. Still I want to look.

This book is an attempt to rediscover the Toronto Carrying Place to retrace its route and its influence on our times, and to find whatever evidence may be left of it today. It is quite literally a trip into the past.

Also my past, as it turns out, but I will try not to be maudlin. My best friend and I both lived in the valley of the Humber, close to the Carrying Place, and spent much of the 1970s roaming up and down the river in our parents smoke-filled cars. Bob really should be writing this book, but since hes not here anymore, Ill have to do it.

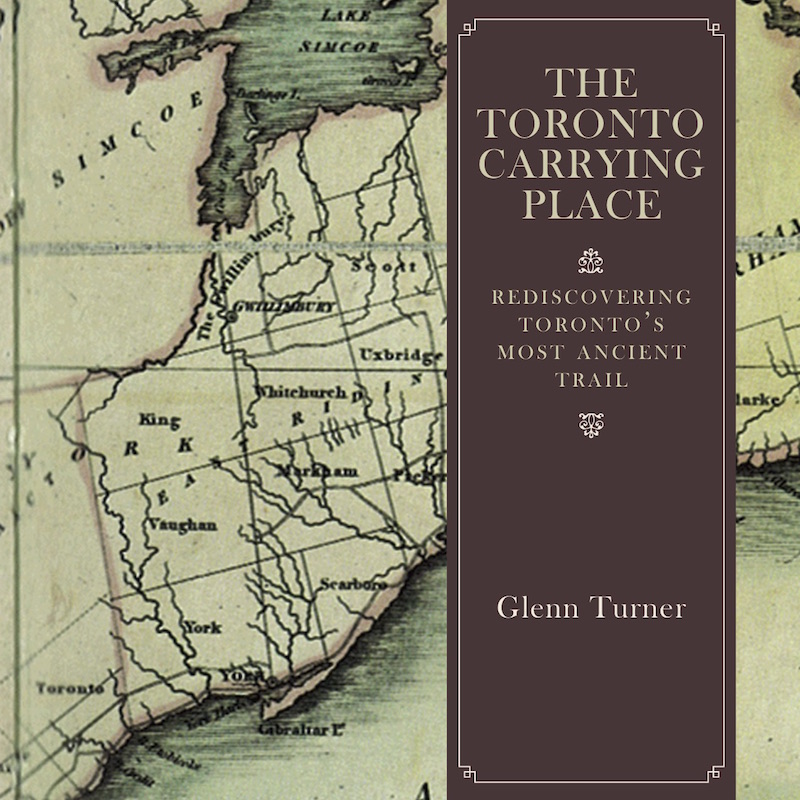

C.W. Jefferys drew this well-known map of the Toronto Carrying Place for Percy Robinsons 1933 book about Torontos early history. The map has been copied, scanned, enhanced, engraved, reprinted, and plagiarized umpteen times since then. Along the route of the trail alone the map appears in four different places, and at least three books published within the last five years have used it. Modern scholarship has suggested changes to some details (like the locations of First Nations villages, for instance), but the map is still considered to be largely accurate, a tribute to Robinsons research and Jefferyss draughtmanship.