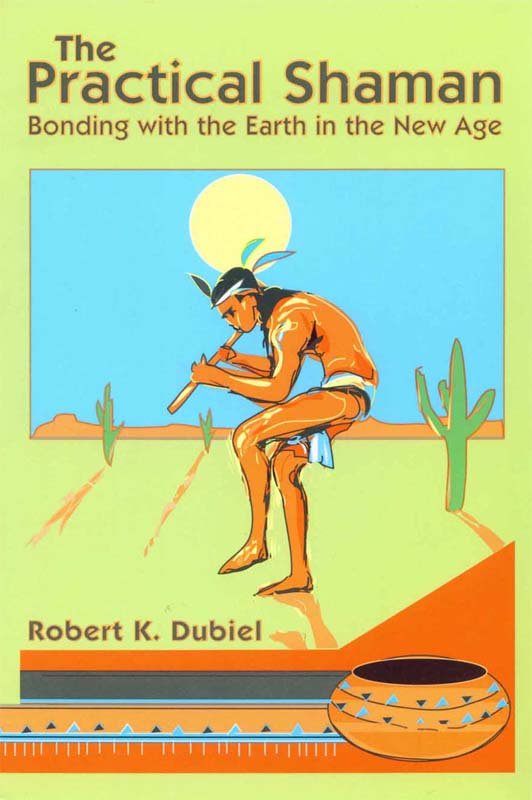

2002 Robert K. Dubiel

All rights reserved

First Edition

Printed in the United States of America.

Speakers Publishing

email:

website: www.zarobert.com

Contents

Acknowledgments

Thanks go out:

To my grandfather, Bruce Garner, whose trust in his intuition gave me inspiration.

To Margaret Sullivan, who originally recorded and later adapted many of the ideas in this book.

To Dr. Kevin Krycka, who channeled the title. To Lisa Ebright, for photo support.

To Fassil and Pam at Nyala Publishing, whose editorial support has been invaluable.

To Sharon Northern for getting me back in touch with my Egyptian roots.

To my students and clients who stimulated the answers to life questions.

To my ancestors and other lifetimes that have supported me on this journey.

And to my fellow Hathors, wherever you are!

FORWARD

What Does It Mean to Be a Shaman?

Shamanism has become a buzzword for those seekers who are consciously on the path of their spiritual growth. In this book, what do I mean by this term? I define shamanism as the practice of drawing on energy from other dimensions of reality to consciously create ones own life and the life of the community one serves.

This statement contains several implications. It assumes that indeed there is another reality, that there are other dimensions of consciousness. It also implies that the individual lives within a community, not separately as an island, but with conscious interaction to activate his or her life purpose. That is, the practice of serving the community assists the shaman in applying the universal principles of co-creation of reality. Getting outside of ones own skin and helping others is a good antidote to the rampant selfishness in todays Western culture that leads to loneliness and isolation.

The shaman of traditional earth-based cultures may have felt a sense of isolation as he or she journeyed to capture information and power from other dimensions. But it was the isolation of solitude which comes from the realization that one is on ones path and that one has ones work to do not the loneliness that comes from not being respected or understood by a materialist culture.

Shamans by their very nature are mystics, people who tap into other dimensions for their answers. Being a mystic means surrendering to the presence of Spirit in ones daily life, sometimes at unexpected moments. Each of us could list occasions when answers or insights came to us unbidden when we least expected them. In my own life I can enumerate: A near death experience in which I received the skein of my life purpose; two spontaneous flashes of the same lifetime, one during dinner, the other out-of-body; an authoritative inner voice warning me of the impending demise of the spiritual organization I was involved with; orders from the inner voice to walk, then run, then walk again to my destination, in order to improve my sense of timing - the list could go on and on. The point is that those of us who accept another reality as part of life will have an easier time receiving messages from Spirit without undue suspicion.

It is important to develop ones own code or system of receiving information, to become proficient at listening. Moreover, with practice one discerns just how much energy is available for each project, and what type of energy it is. Then one will not be disappointed in not winning the lottery, when the energy available is for building a business. One learns to read the state of the energy in the environment and to look for clues on how to work it.

This book consists of a series of short articles, accompanied by exercises to apply the concepts. It presumes some knowledge of traditional shamanic practices in indigenous cultures. If you are unfamiliar with shamanic journeying, I suggest you read the works of Mircea Eliade and Michael Harner. It is not my purpose here to teach a system of Native American shamanism, but rather to illustrate how to work with the life force energy consciously to create everyday reality.

INTRODUCTION

How I Came to Write this Book

I remember my grandfathers serenity as we walked to the dime store when I was four. Many times few words passed between us, but Pa radiated a sense of peace as we moved toward our goal: to buy marshmallow peanuts as Saturday treats for me and his inner child. I wondered at my grandfathers tranquility, for he seemed to live in a world of his own which I could not penetrate, telepath though I was. Many years later, as I was touring North America giving lectures on meditation and reincarnation, he revealed his secret.

My grandfather Bruce Garner was twenty-six (in 1921) when he had a vision while plowing his Tennessee fields one morning. His entire future was shown to him during the course of two hours he plowed straight through and didnt go home for lunch, which was unheard of for him (he loved food). Among the details of Pas vision was my fathers (his future son-in-laws) last name, Dubiel, which he had never heard before. (My parents met in 1948.) Pa saw many circumstances of my parents rocky marriage as well as details of his own life and the lives of those close to him. Evidently everything occurred just as he had seen it up until 1978 when he revealed this vision to my parents, long after my grandmothers death. (He had never told her.)

When he was eighty-three my grandfather predicted the circumstances of my fathers death. Nine years later the situation occurred just as my grandfather had foreseen my father stopped in his car along the side of a country road, doubled over with pain except that my father didnt die. My fathers free will superseded the destiny my grandfather had seen in his vision. Nevertheless, knowing that my grandfather had been clairvoyant was very validating for me in my metaphysical work, as was his special relationship to lightning he had been struck twice directly, with no permanent ill effects.

Gradually I have come to understand that my grandfather was a shaman of the unconscious sort so prevalent in the early years of settled rural America. His garden was his lifeblood; even while working in a factory in Chicago, he managed to turn his backyard into a peaceful haven of morning glories. When Pa retired he immediately moved back to Tennessee where he cultivated about a quarter acre in vegetables until he broke his hip at age ninety-five. After that, when he could no longer crawl around among the peas and beans, his mind failed and he lost his joy in living; he died just after he turned one hundred. For many years Pas health and longevity were an inspiration to the family, but more than that he was a symbol of tranquility and serenity.

My own childhood was stormy and unsettled. We moved constantly my happiest times were between the ages of two and five when my parents and I lived on three farms in northeastern Illinois. I enjoyed having special chickens, my cats, my German Pointer, rabbits, little piglets I also yearned to go off in the woods and visit the coyotes and raccoons that I would see when I accompanied my father on his tractor in the fields. When I was five we moved back to the city. I hated the mentality of the urban kids too harsh, disconnected from the earth; was not fond of school too many confusing energies from other kids for me to sort out properly; and did not appreciate the small town mentality of my mothers family, who had created an emotional replica of rural Tennessee in the middle of the city.