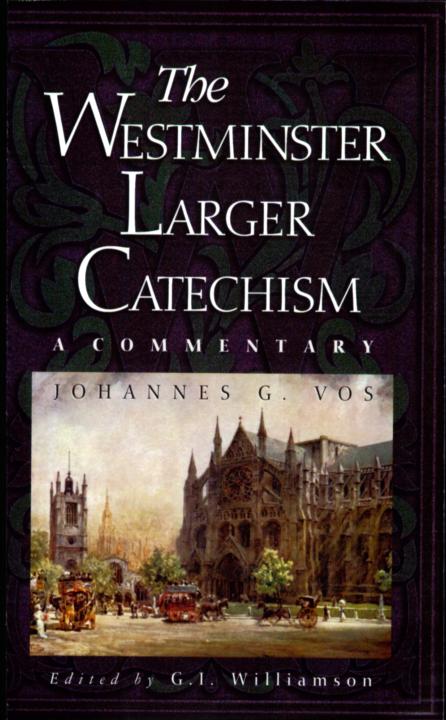

A C 0 M M E N TA R Y

A C O M M E N T A R Y

J 0 H A N N E S (; . V O S

Edited by G. I. Williamson

Introduction by W. Robert Godti-ey

ix

I1'. Robert (:od~rt'y

xxi

Part I What Man Ought to Believe

Part 2 What Duty God Requires of Man

once heard the late ProtessorJohn Murray describe the Blue Batter Faith (affil Lilt, magazine as the best periodical of its kind in the world. I became a faithful reader and, in doing so, became aware of the high quality of the work ofits editor, the Rev. Johannes Geerhardus Vos. One of the finest things that he wrote for that periodical, in my opinion, was his series of studies on the Larger Catechism of the Westminster Assembly.

once heard the late ProtessorJohn Murray describe the Blue Batter Faith (affil Lilt, magazine as the best periodical of its kind in the world. I became a faithful reader and, in doing so, became aware of the high quality of the work ofits editor, the Rev. Johannes Geerhardus Vos. One of the finest things that he wrote for that periodical, in my opinion, was his series of studies on the Larger Catechism of the Westminster Assembly.

OfTice-bearers in conservative Presbyterian churches such as my own are required to "receive and adopt" this catechism as one of the three documents "containing the system of doctrine taught in the Holy Scriptures.'' But it is common knowledge that the Larger Catechism has received tar less attention than either the Shorter Catechism or the Confession of Faith. One reason for this has been the paucity of good study material expounding it. A reprint of the work by Thomas ltidgeley, originally published in 1731, is the only other study I have seen, and for various reasons it is not nearly as usable as this study by Vos.

I ant therefore most happy that Mrs. Marion Vos's widowencouraged me to edit this work, and that the editorial board of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America authorized its publication.

May our sovereign Lord bless this study as a teacher of many who were not present to see it in the original pages of the Blue Banner Faith and Lilc.

W. Robert Godfrey

n 1908 B. 13. Wartield showed himself a master of understatement when he observed: "In the later history of the Westminster forinularies, the Larger Catechism has taken a somewhat secondary place." Compared to the prominence and influence of the Shorter Catechism in Presbyterian circles, the larger Catechism is a very distant second indeed. At least in the United States the Larger Catechism is seldom mentioned, much less studied, as a living part of the Presbyterian heritage. This situation is not new. From the seventeenth century on, the Shorter Catechism received much more attention than did the Larger. Francis Beattie commented a century ago: "For an exposition of the Larger Catechism alone, Itidgeley's Body o/ Diviinity is deserving of notice, when so te\v treatises deal directly with the Larger (;atechism."' In t.ict 1 bonus Itidgeley's two-volume work printed in 1731-33 seems to be the only major work to focus on the Larger Catechism.

n 1908 B. 13. Wartield showed himself a master of understatement when he observed: "In the later history of the Westminster forinularies, the Larger Catechism has taken a somewhat secondary place." Compared to the prominence and influence of the Shorter Catechism in Presbyterian circles, the larger Catechism is a very distant second indeed. At least in the United States the Larger Catechism is seldom mentioned, much less studied, as a living part of the Presbyterian heritage. This situation is not new. From the seventeenth century on, the Shorter Catechism received much more attention than did the Larger. Francis Beattie commented a century ago: "For an exposition of the Larger Catechism alone, Itidgeley's Body o/ Diviinity is deserving of notice, when so te\v treatises deal directly with the Larger (;atechism."' In t.ict 1 bonus Itidgeley's two-volume work printed in 1731-33 seems to be the only major work to focus on the Larger Catechism.

Is such neglect of the larger Catechism justified? Is there value almost years after the writing of the catechism in renewing our appreciation of it? 'hhc answer certainly is yes. The Larger Catechism is a mine of tine gold theologically, historically, and spiritually. This study will delve into this Mine by looking briefly at the preparation of the c attic hisnt, the purposes it was to tultill, and the continuing value of the catechism for the church today.

The Larger Catechism's Preparation and Purpose

'i'he catechetical concerns of the Westminster Assembly were grounded in the Solemn league and covenant that England and Scotland had signed in 1043. Article 1 ofthat covenant declared that we "shall endeavour to bring the (:hurc hies of (;od in the three kingdoms I England, Scotland, and Ire land to the nearest conjunction and uniformity in religion, confession of faith, form of church-government, directory for worship and catechising; that we, and our posterity after us, may, as brethren, live in faith and love, and the Lord may delight to dwell in the midst of us."` Clearly the of a catechism was a significant goal of the alliance.

The responsibility of preparing a catechism was taken very seriously by the Assembly, which appointed a committee to undertake that work.' Although much of the committee's work cannot be reconstructed, we do know some ofthe issues that were debated. The committee proposed a directory of catechizing' and discussed a variety of approaches to writing a catechism. Herbert Palmer wrote a draft of a catechism, but even though he had the reputation as the best catechist in England, his draft was not acceptable to the entire committee. The committee also debated whether or not to include an exposition of the Apostles' Creed, which historically had been a central feature of catechisms." Since the creed was not inspired Scripture, the committee ultimately decided not to include such an exposition.

A key breakthrough in the work of the committee came in January 1647 with the decision to write two catechisms instead of one. That decision seemed to clarify and simplify the work of the committee, after which they progressed rapidly. On January 14, 1647, the Assembly had adopted a motion "that the committee for the Catechism do prepare a draught of two Catechisms, one more large and another more brief, in which they are to have an eye to the Confession of Faith, and to the matter of the Catechism already begun."" George Gillespie observed that the Larger Catechism would be "for those of understanding" while other Scottish Commissioners referred to it as "one more exact and comprehensive." They acknowledged that it had been "very difficult ... to dress up milk and meat both in one dish."" Clearly the Larger Catechism was intended for the more mature in the faith.

How was this Larger Catechism intended to be used' Certainly it was to help the study and growth of those Christians who were ready for the meaty things of the faith. The General Assembly ofthe Church of Scotland in approving the Larger Catechism in 1648 called it "a for catechizing such as have made some proficiency in the knowledge of the grounds of religion.""'

once heard the late ProtessorJohn Murray describe the Blue Batter Faith (affil Lilt, magazine as the best periodical of its kind in the world. I became a faithful reader and, in doing so, became aware of the high quality of the work ofits editor, the Rev. Johannes Geerhardus Vos. One of the finest things that he wrote for that periodical, in my opinion, was his series of studies on the Larger Catechism of the Westminster Assembly.

once heard the late ProtessorJohn Murray describe the Blue Batter Faith (affil Lilt, magazine as the best periodical of its kind in the world. I became a faithful reader and, in doing so, became aware of the high quality of the work ofits editor, the Rev. Johannes Geerhardus Vos. One of the finest things that he wrote for that periodical, in my opinion, was his series of studies on the Larger Catechism of the Westminster Assembly. n 1908 B. 13. Wartield showed himself a master of understatement when he observed: "In the later history of the Westminster forinularies, the Larger Catechism has taken a somewhat secondary place." Compared to the prominence and influence of the Shorter Catechism in Presbyterian circles, the larger Catechism is a very distant second indeed. At least in the United States the Larger Catechism is seldom mentioned, much less studied, as a living part of the Presbyterian heritage. This situation is not new. From the seventeenth century on, the Shorter Catechism received much more attention than did the Larger. Francis Beattie commented a century ago: "For an exposition of the Larger Catechism alone, Itidgeley's Body o/ Diviinity is deserving of notice, when so te\v treatises deal directly with the Larger (;atechism."' In t.ict 1 bonus Itidgeley's two-volume work printed in 1731-33 seems to be the only major work to focus on the Larger Catechism.

n 1908 B. 13. Wartield showed himself a master of understatement when he observed: "In the later history of the Westminster forinularies, the Larger Catechism has taken a somewhat secondary place." Compared to the prominence and influence of the Shorter Catechism in Presbyterian circles, the larger Catechism is a very distant second indeed. At least in the United States the Larger Catechism is seldom mentioned, much less studied, as a living part of the Presbyterian heritage. This situation is not new. From the seventeenth century on, the Shorter Catechism received much more attention than did the Larger. Francis Beattie commented a century ago: "For an exposition of the Larger Catechism alone, Itidgeley's Body o/ Diviinity is deserving of notice, when so te\v treatises deal directly with the Larger (;atechism."' In t.ict 1 bonus Itidgeley's two-volume work printed in 1731-33 seems to be the only major work to focus on the Larger Catechism.