MIND

OF A

THE

MIND

OF A

LARS CHITTKA

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2022 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to .

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-18047-2

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-23624-7

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Alison Kalett and Hallie Schaeffer

Production Editorial: Jenny Wolkowicki

Text design: Wanda Espaa

Jacket design: Lauren Michelle Smith

Production: Jacqueline Poirier

Publicity: Sara Henning-Stout and Kate Farquhar-Thomson

Copyeditor: Annie Gottlieb

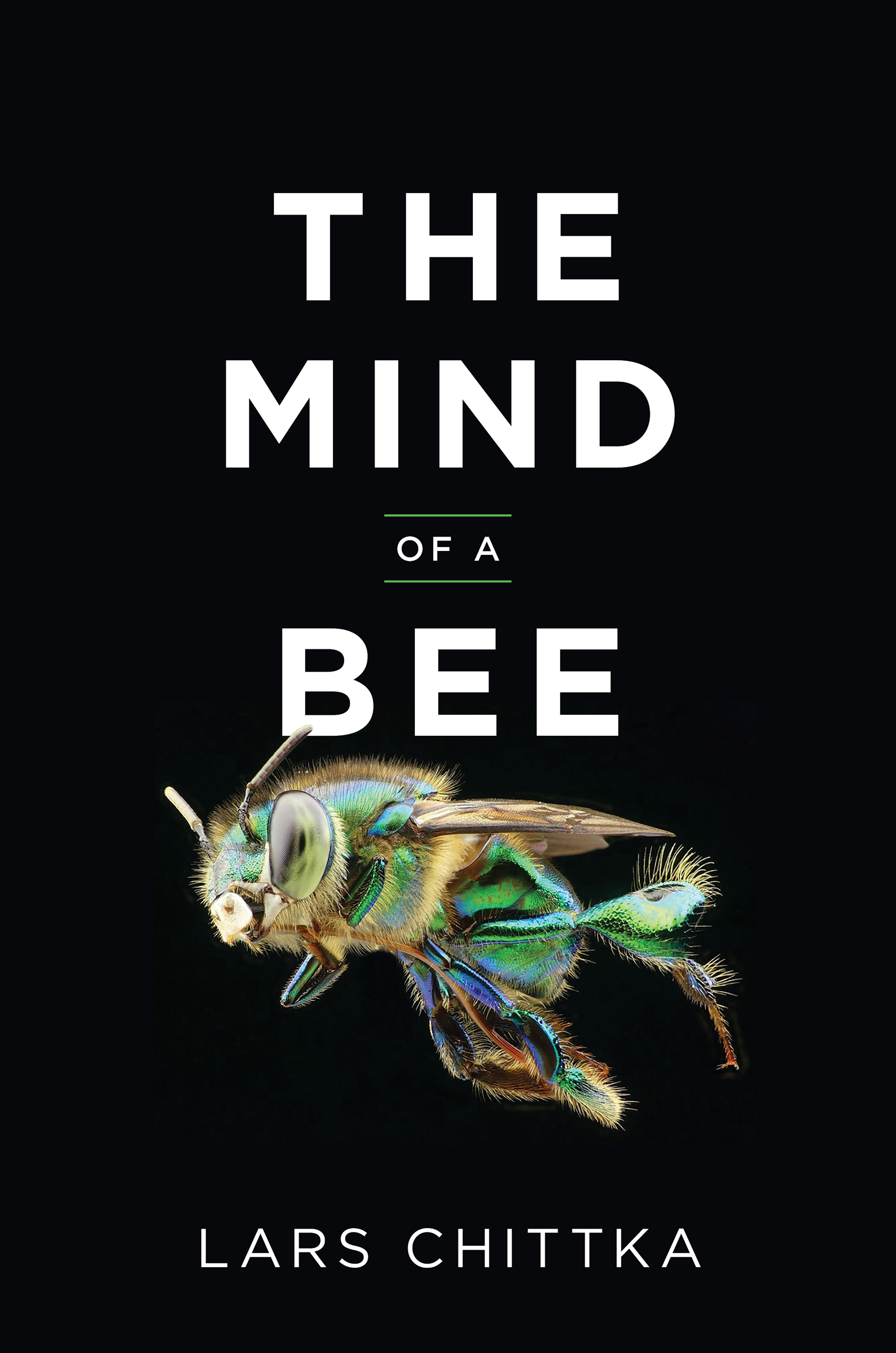

Jacket image: Orchid bee, Euglossa sp. Euglossini. Andreas Kay

For Marlene Smano Chong

CONTENTS

Introduction

Let us suppose that an inhabitant of Venus or Mars were to contemplate us from the height of a mountain, and watch the little black specks that we form in space, as we come and go in the streets and squares of our towns.All he could do, like ourselves when we gaze at the hive, would be to take note of some facts that seem very surprising; and from these facts to deduce conclusions probably no less erroneous, no less uncertain, than those that we choose to form concerning the bee.

Whither do they tend, and what is it they do? he would ask, after years and centuries of patient watching. What is the aim of their life, or its pivot?I can see nothing that governs their actions. The little things that one day they appear to collect and build up, the next they destroy and scatter. They come and they go, they meet and disperse, but one knows not what it is they seek.

Maurice Maeterlinck, 1901

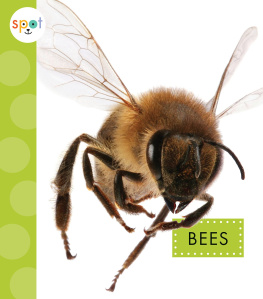

Understanding the minds of alien life-forms is not easy, but if you relish the challenge, you dont have to travel to outer space to find it. Alien minds are right here, all around you. You wont necessarily find them in large-brained mammalswhose psychology is sometimes studied for the sole purpose of finding human-ness in slightly modified form. With insects such as bees, there is no such temptation: neither the societies of bees nor their individual psychology are remotely like those of humans (). Indeed, their perceptual world is so distinct from ours, governed by completely different sense organs, and their lives are ruled by such different priorities, that they might be accurately regarded as aliens from inner space.

Figure 1.1.The strangeness of the bees world.Many aspects of a bees life, or its communities, have no parallel in the human realm. Unique forms of sensory perception, instinctual behavior, cognition, and social interaction can give rise to structures such as the mathematically optimal honeycomb, matchless in the animal kingdom in terms of its regularity and functionality.

Insect societies may look to us like smoothly oiled machines in which the individual plays the part of a mindless cog, but a superficial alien observer might come to the same conclusion about a human society. Over the course of this book, it will be my goal to convince you that each individual bee has a mindthat it has an awareness of the world around it and of its own knowledge, including autobiographical memories; an appreciation of the outcomes of its own actions; and the capacity for basic emotions and intelligencekey ingredients of a mind. And these minds are supported by beautifully elaborate brains. As we will see, insect brains are anything but simple. Compared to a human brain with its 86 billion nerve cells, a bees brain may have only about a million. But each one of these cells has a finely branched structure that in complexity may resemble a full-grown oak tree. Each nerve cell can make connections with 10,000 other oneshence there may be more than a billion such connection points in a bee brainand each of these connections is at least potentially plastic, alterable by individual experience. These elegantly miniaturized brains are much more than input-output devices; they are biological prediction machines, exploring possibilities. And they are spontaneously active in the absence of any stimulation, even during the night.

What Its Like to Be a Bee

To explore what might be inside the mind of a bee, it is helpful to take a first-person bee perspective, and consider which aspects of the world would matter to you, and how. I invite you to picture what its like to be a bee. To start, imagine you have an exoskeletonlike a knights armor. However, there isnt any skin underneath: your muscles are directly attached to the armor. Youre all hard shell, soft core. You also have an inbuilt chemical weapon, designed as an injection needle that can kill any animal your size and be extremely painful to animals a thousand times your sizebut using it may be the last thing you do, since it can kill you, too. Now imagine what the world looks like from inside the cockpit of a bee.

You have 300o vision, and your eyes process information faster than any humans. All your nutrition comes from flowers, each of which provides only a tiny meal, so you often have to travel many miles to and between flowersand youre up against thousands of competitors to harvest the goodies. The range of colors you can see is broader than a humans and includes ultraviolet light, as well as sensitivity for the direction in which light waves oscillate. You have sensory superpowers, such as a magnetic compass. You have protrusions on your head, as long as an arm, which can taste, smell, hear, and sense electric fields (). And you can fly. Given all this, whats in your mind?

The Challenges of Being a Forager in the Wild

What is in an animals (including a humans) mind is a mixture of information from its evolutionary history; information passing through the sensory filters it has acquired during evolution; information it has memorized from its experience; and things it might imagine, or anticipate. To explore the possible contents of a mind, it helps to think about what matters to the animal in questionwhats important in that animals daily life. For example, one thing you can be fairly sure is