This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by John H. Hanson

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-02619-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-02933-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-02951-5 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18 17

Preface and Acknowledgments

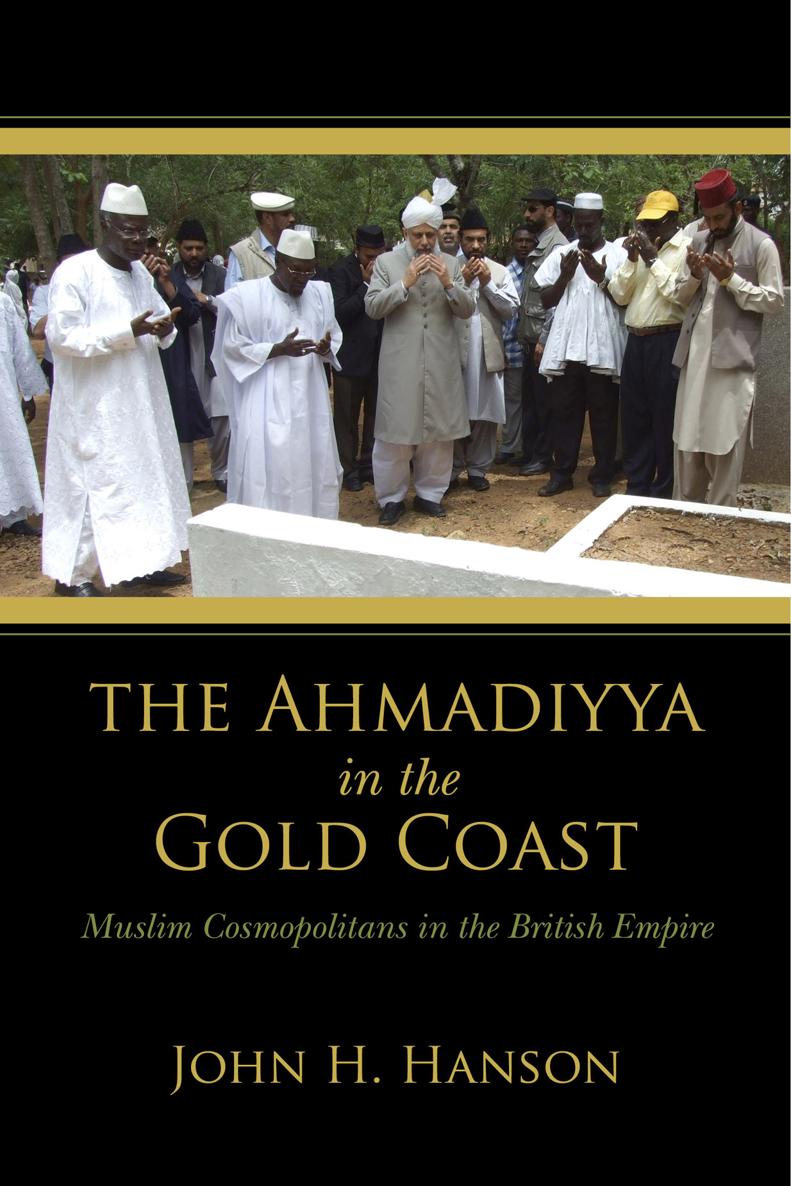

VISIONARY EXPERIENCES and religious conversations brought West Africans and South Asians together into the Ahmadiyya, a Muslim movement with origins in British India. Dreams led to discussions that pointed to new religious horizons: nearly a century ago West Africans invited an Ahmadi missionary to visit, accepted the Ahmadiyya, and supported the founding of an Ahmadi mission and school in Ghana, then known as the Gold Coast. My interest in this past was sparked by my own experiences and conversations in Wa, a town in northwestern Ghana where I was conducting research. Shortly after arriving, I was on the back of Latif Khalids motorbike when we hit a goat that darted in front of us. We survived, as did the goat, but Latif had a bloody gash on his leg. As I dressed his wound, Latif, my research assistant, asked about my first-aid kit, something I had not packed on previous outings. I replied that the night before I had dreamed about having an accident; I added, as an explanation, that my malaria prophylaxis caused me, someone who rarely dreamed, to do so vividly. But Latif, an Ahmadi Muslim, engaged me at length about the significance of dreams in the history of the Ahmadiyya. This exchange was the first of many discussions, in the months and years that followed, about visionary experiences and religious conversations involving pioneering Ahmadi Muslims in the Gold Coast. Ghanaians repeat these accounts to others, including Khalifatul Masih Masroor Ahmad, the current leader of the Ahmadiyya, who visited Ghana and heard about dreams in the company of Maulvi Abdul Wahab Adam, then head of the Ghanaian branch of the movement, in the Ahmadi cemetery at Ekrawfo, Ghana. I interpret these oral accounts and others as a historian, placing them in a context and listening in light of what I learn in written materials.

I build on the work of other historians, but the perspectives in Ahmadi accounts leads my analysis in a different direction than the approach taken in Humphrey J. Fishers Ahmadiyyah: A Study in Contemporary Islam on the West African Coast. My analysis also differs from Ivor Wilkss chapter on the Ahmadiyya in Wa and the Wala. The Ahmadi narratives inspired me to probe more deeply than others had in archives and libraries, where I discovered texts that illuminated and amplified Ahmadi memories. I argue from this evidence for a long history of African initiative that preceded the arrival of the Ahmadiyya and paved the way for its success. The result is this book. As a historical account, much of the analysis is based on written materials, but the insights came from Ahmadi narratives. I am grateful to those who shared information with me, some listed in my bibliography and others not because their stories concerned the postcolonial past, beyond the chronological frame of this book.

Grants and fellowships allowed me to pursue this research. I was in Wa on a Fulbright fellowship, and the National Endowment for the Humanities funded Friday Prayers at Wa, an audiovisual work on the CD-ROM Five Windows into Africa. Additional research was launched in subsequent summer trips to Ghana funded by Indiana University. Reflection on this project occurred at the Library of Congresss Kluge Center, where I was funded by a Rockefeller fellowship. Then I conducted an extended period of research in Ghana and the United Kingdom, supported by a Fulbright-Hays fellowship. Additional research and the drafting of several chapters occurred at the National Humanities Center through support from a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. I completed research in British archives and libraries and wrote the complete draft of the current manuscript with support from the Gerda Henkel Foundation. Indiana Universitys Institute for Advanced Study provided financial support as I made revisions and prepared the manuscript for publication.

The book is the result of numerous visits abroad, and it would not have been possible without the hospitality and support of many people. First and foremost, I must acknowledge the assistance of Ahmadi Muslims, who accepted me not as a fellow believer but as a researcher in their midst. I met the current leader, Khalifatul Masih Masroor Ahmad, near the completion of this book, and he and others assisted in providing access to issues of Review of Religions I could not find in libraries. Specific thanks is due to Umar Ahmad, Omair Aleem, Asif M. Basit, Amer Safir, and Hassan Wahab, who helped provide these materials and also assisted in the process of obtaining permissions to use images from Review of Religions. Crucial to my work at its outset was Maulvi Mohammed bin Salih, the current ameer and missionary-in-charge in Ghana, who assisted my initial research in Wa by opening many doors and discussing the Wala past at length. As my project expanded beyond Wa, I relied on the assistance, encouragement, and insights of the late Maulvi Abdul Wahab Adam, the previous ameer and missionary-in-charge in Ghana, a towering public intellectual whom I feel fortunate to have known: I lament not completing this book before he died.

Interviews in Ghana depended on the assistance of a great many people, who dropped other activities to assist me. In Asante I am grateful to the following: in Kumasi and neighboring villages, Nana Abubakar, Ismael Addo, Y. K. Agyare, Al-Hajjiya Ayesha Bonsu, Abdullah Nasir Boateng, Al-Hajj Adams Dawoode, Nana Muhammad K. Duah, Al-Hajj Yusuf Ahmad Edusei, A. Y. Fareed, I. K. Gyasi, Al-Hajj Nuhu Kofi, Opanin Tahir, Al-Hajjiya Ayesha Tiwaa, and Dr. Muhammad Zafrullah; in Asakore, Dr. Mahmud Ahmad Butt and Usman Mensah; in Asokwa, Ibrahim Addo and Tahir Hammond; in Fomena, Ahmad Boakye, Nazir A. Keelson, and Sadique Nuamah; in Kokofu, Dr. Hameed Nasullah; in Mampon, Ibrahim Agyeman, Abdullah Nasir Boateng, and Al-Hajj Mahmud K. Bobbrey; in Peminase and Pramso, Alhassan Atta, Dr. Al-Hajj Mohammad bin Ibrahim, Fazlu Ilah, and Hakeem Kontor. In the Central Region, I am indebted to Usman Abekah, Jibreel Adam, Al-Hajj Hakeem Amissah, Al-Hajj Abubakar Anderson, Sarah Anderson, Tahir Andze, Adam Appiah, Zahoor Arthur, Hussain Assopiah, Al-Hajj Ismail Biney, Lateef Esuam, Nuruddeen Inkoom, Dr. Nasrullah Khan, Nana Muhammad Ogyefo-Yena, and Yusuf Quandze. In Wa I benefited from the assistance of Wa Na Momori Bondiri II, Limam Al-Hajj Yakubu Issaka, Latif Khalid, Mahmud Khalid, Malam Taslim Mahama, E. M. Salifu, Alhassan bin Salih, Abdul Rahman Yahaya, and Dawud R. Yahaya. If I inadvertently omitted someone, please accept my apologies.